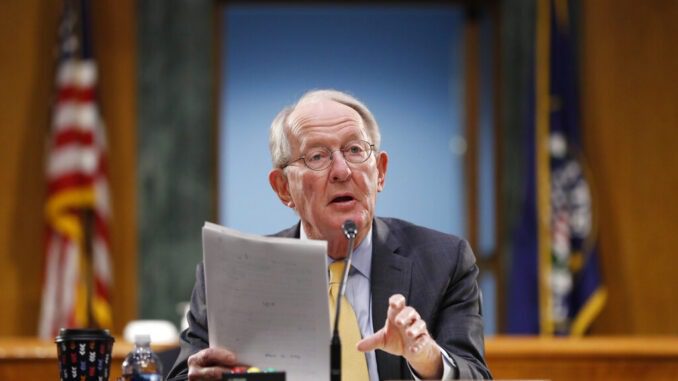

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Sen. Lamar Alexander, a Tennessee political legend who forged a productive path as a Senate institutionalist after tours as governor and Cabinet secretary, said goodbye to the chamber on Wednesday, advising his colleagues to seek broadly backed, durable solutions to the nation’s problems rather than succumb to easy partisanship.

The three-term Republican had his most noteworthy success on education and health policy over the 18-year tenure, becoming a beloved bipartisan figure in an increasingly polarized, dysfunctional Senate.

“It’s hard to get here, it’s hard to stay here, and while we’re here we might as well try to accomplish something good for the country,” Alexander said.

Alexander left the GOP’s leadership track during the Obama years to focus on his committee work. As chairman of the HELP panel, Alexander shepherded a 2015 rewrite of elementary and high school education that swept through the Senate with near-universal support. His most powerful ally, typically, was a Democrat, Washington liberal Patty Murray, who linked arms to defend their efforts and deliver a bill supported by liberals and conservatives alike.

“Lamar listened to me when I told him we should write a bill together, rather than amending the Republican bill he had begun working on,” Murray said. “With our HELP committee members, we were able to write and pass a new K-12 public education bill that fixed the most broken parts of No Child Left Behind.”

Alexander, 80, served as education secretary under President George H.W. Bush after eight years as Tennessee governor.

Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., whose relationship to Alexander dates to their time as ambitious twenty-somethings in Washington in the 1960s, grew emotional as he recounted his friend of five decades. They got to know each other as aides during an era in which the chamber was stacked with national figures and debated issues like civil rights and the Vietnam War.

“Sen. Alexander knows about 50 different issues as well as most senators know three or four,” McConnell said. “He is hands-down one of the most brilliant, most thoughtful, and most effective legislators any of us have ever seen.”

Alexander played central roles in recent public lands legislation, as well as bills to combat opioids, find new cures, and protect music copyrights.

Alexander offered a defense of the chamber’s traditions, especially the filibuster that forces consensus — or, increasingly, gridlock — upon the Senate. He noted that he worked for GOP Sen. Howard Baker, who served as majority leader during Ronald Reagan’s first term. He holds Baker’s seat, and is only the latest of a series of national figures from the Volunteer State to serve in the Senate, a roster that includes former Vice President Al Gore and former GOP Majority Leader Bill Frist.

Alexander will be replaced by Nashville businessman Bill Hagerty, a Republican backed by President Donald Trump.

He reminded a crowded Senate that durable changes like civil rights legislation, Social Security and Medicare require bipartisanship and big tallies.

“Those bills didn’t just pass. They passed by big margins. The country accepted them and they’re going to be there for a long time,” Alexander said.

Alexander ran unsuccessfully for president in 1996 on a slogan slamming Congress: “Cut their pay and send them home.” But when he joined the Senate in 2003, he assumed a career track as an institutionalist, securing a valued spot on the Appropriations Committee and joining the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, which he would later chair.

Alexander told his colleagues, including more junior, impatient Democrats who boasted they would get rid of the filibuster if Democrats retake the chamber, that taking such a step would ruin the Senate.

“Ending the filibuster would destroy the impetus for forcing the broad agreements I’ve been talking about and it would unleash the tyranny of the majority to steamroll the rights of the minority,” Alexander said.