WASHINGTON, D.C. — In a decision flavored with references to “Hamilton” and “Veep,” the Supreme Court ruled unanimously Monday that states can require presidential electors to back their states’ popular vote winner in the Electoral College.

The ruling, in cases in Washington state and Colorado just under four months before the 2020 election, leaves in place laws in 32 states and the District of Columbia that bind electors to vote for the popular-vote winner, as electors almost always do anyway.

So-called faithless electors have not been critical to the outcome of a presidential election, but that could change in a race decided by just a few electoral votes. It takes 270 electoral votes to win the presidency.

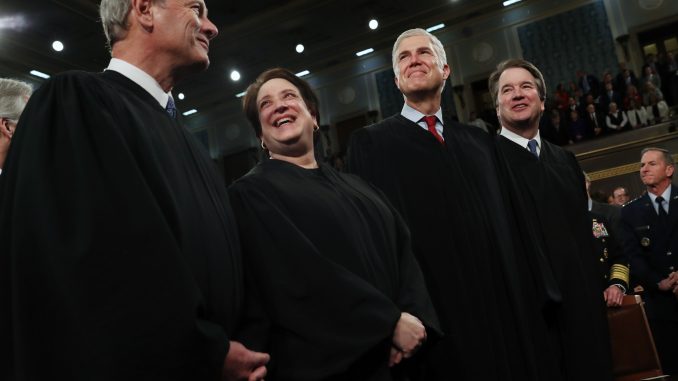

A state may instruct “electors that they have no ground for reversing the vote of millions of its citizens,” Justice Elena Kagan wrote in her majority opinion that walked through American political and constitutional history with an occasional nod to pop culture.

Such an order by a state “accords with the Constitution — as well as with the trust of a Nation that here, We the People rule,” Kagan wrote.

President Donald Trump has been both a critic and fan of the Electoral College.

In 2012, he tweeted, “The electoral college is a disaster for a democracy.” But in November 2016 after he won he presidency despite losing the popular vote to Hillary Clinton, he tweeted, “The Electoral College is actually genius in that it brings all states, including the smaller ones, into play.”

Monday’s ruling was not about the legitimacy of the Electoral College or an ongoing effort to effectively eliminate it by having states commit to support the national popular vote winner. That proposal, sure to be challenged in the courts, wouldn’t take effect unless states constituting a majority of electoral votes endorsed it.

The court acted on another issue, whether electors are free agents regardless of what voters in their states decide. The justices scheduled arguments for last spring so they could resolve the issue before this year’s presidential election rather than amid a potential political crisis after the country votes.

Kagan recounted how the Constitution’s original rules for presidential electors sowed confusion because there was no distinction between votes for president and vice president. She noted that the results of the 1796 election gave President John Adams his political rival, Thomas Jefferson, as vice president, a situation Kagan called “fodder for a new season of Veep.”

Things got worse four years later when Jefferson and Aaron Burr finished in an Electoral College tie, sending the election to the House of Representatives. It took 36 ballots and the influence of Alexander Hamilton to elect Jefferson as president, Kagan wrote.

“Alexander Hamilton secured his place on the Broadway stage—but possibly in the cemetery too—by lobbying Federalists in the House to tip the election to Jefferson, whom he loathed but viewed as less of an existential threat to the Republic,” she said.

Those two elections led to the adoption of the Twelfth Amendment, which produced the Electoral College rules in use today, with separate ballots for president and vice president. “By then, everyone had had enough of the Electoral College’s original voting rules,” Kagan wrote.

The closest Electoral College margin in recent years was in 2000, when Republican George W. Bush received 271 votes to 266 for Democrat Al Gore. One elector from Washington, D.C., left her ballot blank.

When the court heard arguments by telephone in May because of the coronavirus outbreak, justices invoked fears of bribery and chaos if electors could cast their ballots regardless of the popular vote outcome in their states.

The issue arose in lawsuits filed by three Hillary Clinton electors in Washington state and one in Colorado who refused to vote for her despite her popular vote win in both states in 2016. In so doing, they hoped to persuade enough electors in states won by Trump to choose someone else and deny him the presidency.

The federal appeals court in Denver ruled that electors can vote as they please, rejecting arguments that they must choose the popular-vote winner. In Washington, the state Supreme Court upheld $1,000 fines against the three electors and rejected their claims.

The Supreme Court affirmed the Washington decision and reversed the ruling from Colorado.

In all, there were 10 faithless electors in 2016, including a fourth in Washington, a Democratic elector in Hawaii and two Republican electors in Texas. In addition, Democratic electors who said they would not vote for Clinton were replaced in Maine and Minnesota.

The closest Electoral College margin in recent years was in 2000, when Republican George W. Bush received 271 votes to 266 for Democrat Al Gore. One elector from Washington, D.C., left her ballot blank.

The Supreme Court played a decisive role in that election, ending a recount in Florida, where Bush held a 537-vote margin out of 6 million ballots cast.

The justices scheduled separate arguments in the Washington and Colorado cases after Justice Sonia Sotomayor belatedly removed herself from the Colorado case because she knows one of the plaintiffs.

In asking the Supreme Court to rule that states can require electors to vote for the state winner, Colorado had urged the justices not to wait until “the heat of a close presidential election.”

Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser, who argued his state’s case at the Supreme Court, called the outcome “a win for orderly elections and our constitutional democracy.”

Reacting to the decision Monday, the lawyer for the electors who challenged the state rules said he’s glad the court acted now. “Obviously, we don’t believe the Court has interpreted the Constitution correctly. But we are happy that we have achieved our primary objective — this uncertainty has been removed. That is progress,” lawyer Lawrence Lessig said.