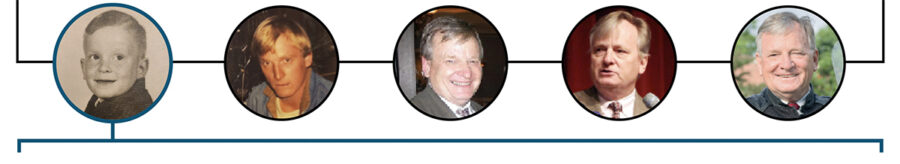

This is the first story in a five-week series on the life and career of outgoing North Carolina Treasurer Dale Folwell.

RALEIGH — Sitting behind his desk surrounded by shelves of awards, family photos and memorabilia collected over the years, North Carolina State Treasurer Dale Folwell spoke softly about his early years living and working in the Winston-Salem area.

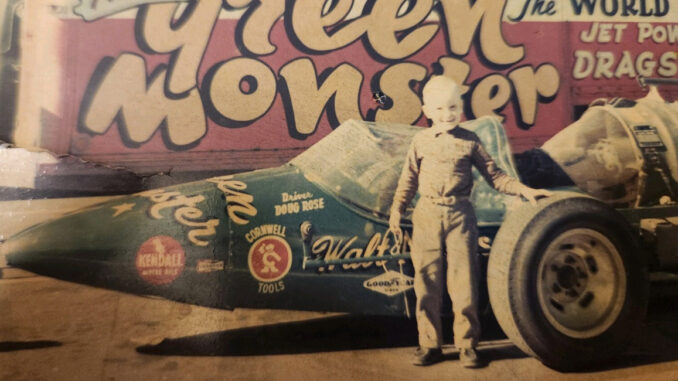

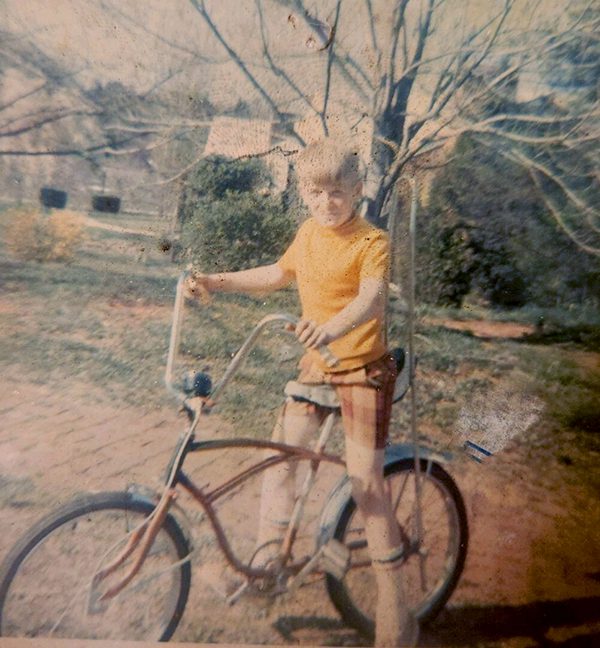

The pictures and keepsakes offer just a glimpse into the life of the 65-year-old North Carolina state treasurer, a man whose humble beginnings, love of motorcycles, diligent work ethic and passion for public service combined to help reach heights many thought improbable.

“I would say that my childhood, like a lot of children that were born in the late ’50s and early ’60s, changed in an unexpected way with the divorce of my parents,” Folwell said in a wide-ranging interview on his personal life and career with North State Journal. “So I often describe my situation as being poor in resources but rich in opportunity.”

He said he was born in the “old Rex hospital,” the same place he later had an office as assistant secretary of commerce overseeing the division of employment security.

“My office was literally one floor below the maternity ward where my mom first saw me in 1958,” Folwell said. His family had stops in Garner and Florida before settling in Winston-Salem. “And then that’s where I spent the rest of my life.”

Folwell, the youngest of children, described his early education as “very nontraditional” and said he was told in high school that he had an IQ of 108, which is fairly average.

“I had never made 100 on anything before, so I was ecstatic of where I might have gotten eight extra credit points,” Folwell said with a laugh. “I’ve since learned that the 108 is not so hot and that, generally told based on some guidance I was given, I was going to make my living for the rest of my life with my hands and my back and my feet. So I decided I was going to be the best at that.”

Folwell started working at around age 10 and described being in class during high school for about an hour and a half a day.

He quickly built a diverse resume, delivering papers for the Salem Journal and Sentinel, working at the Cloverdale Shell when he was 11 years old, and serving as a dishwasher and, later, night cook at Mayberry’s Farmers Dairy Bar in Winston-Salem.

He also had second shift work at the Coca-Cola bottling plant, handling the loading of pallets carrying 55-pound cases of glass Coca-Cola bottles.

“When you’re that young and you work at a bottling company plant, you typically get assigned the hardest jobs,” Folwell said. “And the hardest jobs that Coca-Cola bottling company back then were hand-loading the 64-ounce glass cases of Coca-Cola.”

On the weekends, Folwell pulled stock at Coca-Cola but also started finding work in one of his passions as a motorcycle racing mechanic. While working as a mechanic, an overlapping opportunity arose with the expansion of Krispy Kreme and its vehicle fleet.

“I found out about the fact they pay people to take these vehicles places, so I would coordinate my racing mechanic activities with the racing schedule with wherever Krispy Kreme may need some of these vehicles,” Folwell said. “So in some instances, I get paid to drive the van to Louisville, Kentucky, or Indianapolis, or Houston or whatever — I get paid to drive the van there. And then I get paid to be the mechanic while I was there, and then I drive back with the team back to Winston-Salem.”

During one of his van-driving motorcycle racing trips, he met Larry Tuttle, a man who would change Folwell’s career trajectory.

“Sometimes it could be five weeks or five months or 50 years before you realize what somebody may have done for you in ways that you didn’t really appreciate at the time,” Folwell said of meeting Tuttle, who encouraged him to come to work at his garbage collection company.

Tuttle described the work as picking up trash 20 hours a week at 1,000 houses, and it paid $10 more an hour than Folwell was making at his other job at the time. The work, however, regularly took Folwell 40 hours to complete, affecting his job as a mechanic.

It also presented an opportunity.

Folwell presented Tuttle with a proposal to cut costs and time spent by ending service to customers who had not paid in years. The plan earned Folwell a $50 raise, and the amount of work became closer to the original 20-hour schedule he was originally offered.

In 1981, however, Tuttle told Folwell he had “too good a head on your shoulders and you’re too stubborn and you’re too smart to be a garbage collector.”

“I knew I had to leave, but I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know where I was going to go,” Folwell said quietly.

Eventually, he walked to Winston-Salem State and enrolled in some courses.