What a difference a century makes. One hundred years ago, America was entering into its quadrennial presidential election campaign under circumstances quite different from those facing us today.

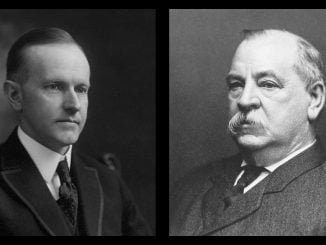

Republican incumbent President Calvin Coolidge was facing Democratic challenger John W. Davis. An accidental president, Coolidge had acceded to the presidency on the death of Warren Harding in 1923 and was still in something of a honeymoon period as the 1924 campaign began.

As a solid conservative Republican, Coolidge had won a succession of Massachusetts elections, serving as town alderman, state senator, lieutenant governor and governor. In 1919, he achieved national prominence for his successful diffusion of the Boston police strike with his terse declaration, “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, anytime.”

In 1920, the GOP convention nominated Coolidge as Harding’s running mate as the party sought a return to “normalcy.”

While the country was still getting acquainted with President Coolidge in 1924, two impressions were already indelibly stamped on voters’ minds. Coolidge was firmly committed to continuing the conservative policies of Harding — tax reduction and limited government were the keystones of the Harding/Coolidge administration and would continue under Coolidge.

In addition, it was clear to voters by 1924 that Coolidge was a man of unimpeachable integrity. He was the embodiment of classic New England virtues: honesty, thrift, lack of pretense, dignity and common sense. The taint of the emerging Harding scandals left Coolidge unscathed.

Davis was also an accidental candidate. He had risen from West Virginia obscurity as a young congressman to serve as solicitor general, ambassador to Great Britain and successful Wall Street lawyer. In 1924, the Democratic Party was bitterly divided between the urban, Catholic forces led by New York Gov. Al Smith and the rural, Protestant faction led by William G. McAdoo. When the convention deadlocked for an unprecedented 102 ballots, Davis was nominated on the 103rd ballot and charged with bringing some sense of unity to the unruly Democrats.

While Davis was not well known among voters, he — similarly to Coolidge ― presented two defining attributes. He was from the conservative wing of the Democratic Party, which had long championed Jeffersonian values of limited government. In addition to establishing an impressive record of accomplishment as a constitutional lawyer, Davis was seen as a man of deep integrity who might bring unity to the fractured Democrats. As columnist Walter Lippmann noted, “Davis’ nomination was the result of confidence in his character rather than of studied agreement with his views.”

At the campaign’s outset, several things became quite clear. There were few substantial differences between Coolidge and Davis. The Democrats’ best issue should have been corruption, but Coolidge was able to stand apart from the Harding scandals. Davis boldly denounced the Ku Klux Klan, which was a significant factor both nationally and within the Democratic Party, and urged Coolidge to follow suit. Coolidge declined to respond to Davis’ challenge, but Coolidge’s record on civil rights made clear his opposition to the Klan.

On matters of tax policy and limited government, there was virtually no difference between the two candidates. As the old progressive Democratic war horse William Jennings Bryan lamented. “Davis is a man of fine character. So is Coolidge. There is no difference between them.” Their only significant policy difference was over tariffs. Coolidge was a pro-tariff Republican, while Davis was a traditional Democrat free-trader.

Both men spoke eloquently of tax policy in moral terms. Coolidge believed, “The wise and correct course to follow in taxation and all other economic legislation is not to destroy those who have already secured success but to create conditions under which everyone will have a better chance to be successful.”

Davis voiced a similar view: “Taxation can justly be levied for no purpose other than to provide revenue for the support of the government. To tax one person, class or section to provide revenue for the benefit of another is none the less robbery because done under the form of law and called taxation.”

Coolidge sounded the same note: “The collection of any taxes which are not absolutely required, which do not beyond reasonable doubt contribute to the public welfare is only a species of legalized larceny.” Both men believed in Coolidge’s moralistic conclusion, “I favor the policy of economy not because I wish to save money, but because I wish to save people.”

As the campaign unfolded in the fall of 1924, Coolidge was clearly dealt a winning hand. A strong economy, the advantages of incumbency, a united GOP and successful fundraising all favored Coolidge, and he played his hand flawlessly. Davis’ campaign was hampered by a fractured Democratic Party, an absence of defining policy differences with Coolidge, and Coolidge’s popular incumbency.

Perhaps the defining characteristic of this race was the civility and dignity with which these two men conducted themselves.

“There was something more to Coolidge and Davis,” Columnist Fred Barnes wrote. “They grew up in small towns — Coolidge in Vermont, Davis in West Virginia — and were gentlemen admired for their personal integrity and unblemished morality. Coolidge was famous for being terse. Davis was noted for his graciousness. They were neither mean-spirited nor power hungry. I can’t recall a presidential race in modern times between two such honorable men.”

We can only hope that someday history might repeat itself.

Garland S. Tucker III, retired chairman and CEO of Triangle Capital Corporation, is author of “Conservative Heroes: Fourteen Leaders Who Shaped America — Jefferson to Reagan” (ISI Books) and “The High Tide of American Conservatism: Davis, Coolidge and the 1924 Election” (Emerald Books).