For those of a certain age, or with more than a woke education, the attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump brings back echoes of history.

Not exactly the history of the abysmal political year of 1968, which saw the murders of Martin Luther King Jr., 39, and Robert F. Kennedy, 42, riots in major cities across the nation — especially violent in Washington, D.C. — and violent demonstrations and a pitched battle during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. But just as Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York noted as Ronald Reagan was recovering from his gunshot wound, this time, the nation could take heart because the assassin’s target survived.

The year 1968 saw an exhausted 59-year-old president, Lyndon Johnson, withdraw his candidacy for reelection, and conventional and (then) not widely disliked 55-year-old Richard Nixon win the election. Neither President Joe Biden, 81, nor Trump, 78, fits into this script.

The more illuminating analogy to the two transcendental events of recent weeks — Biden’s debate performance on June 27 and the attempted assassination of Trump on July 13 — are things that happened some 104 years ago, in the presidential campaign cycle of 1920.

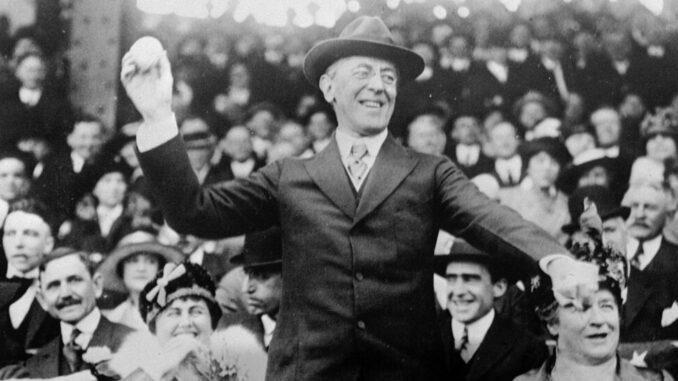

That’s not a campaign cycle much remembered because of its politically incorrect result — the repudiation of Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, a sentimental hero of liberals who applaud his scorn of constitutional limitations and conveniently forget his record as chief presidential enforcer of racial segregation in government.

Those were tumultuous times. Some 116,000 Americans died in 18 months during World War I, and even after the November 1918 armistice, fighting continued in the former Czarist and Ottoman empires, including a temporarily independent Ukraine. There were communist coups in Munich, Berlin and Budapest, and many feared that the totalitarians who turned out to tyrannize Russia for 70 years would do so elsewhere.

Including here. Revolutionaries in June 1919 bombed the Washington, D.C., townhouse of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, threatening his neighbors Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. Unknown radicals in September 1920 set off a bomb on Wall Street across from the J.P. Morgan & Co. building, killing dozens.

Wilson’s administration had jailed former Socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs in 1918 merely for speaking out against the draft, but other targets of the raids organized by the young Justice Department lawyer J. Edgar Hoover were bent on violent overthrow of a system, much as violent pro-Palestinian demonstrators threaten on campuses and in downtowns today.

Other menacing events resemble those of recent years. There were numerous race riots in 1918 and ’19, mostly with whites attacking blacks, just as there were numerous “mostly peaceful” riots, mostly of blacks destroying billions of dollars of property, in 2020 and ’21. There was a worldwide influenza epidemic, first experienced in U.S. Army camps, which killed millions here and around the world and resulted in varied restrictive measures — echoes of COVID-19, quite possibly likely incubated in a U.S.-financed Chinese laboratory.

The post-WWI economy oscillated between sharp recession and strong inflation, which Americans had not experienced for decades. Meanwhile, the vast Ellis Island immigration in the quarter-century before world war broke out led to demands for barring most newcomers from historically unfamiliar cultures.

Amid this turbulence, the American president was mostly absent. Wilson collapsed in October 1919 on a cross-country train trip to rally support for the Treaty of Versailles he had negotiated, and for months was incapacitated by a stroke. His wife and doctor barred access to Cabinet members, congressional leaders and the press. The required two-thirds majority of the Senate was willing to ratify the treaty only with reservations preserving Congress’s constitutional power to declare war. Edith Wilson told them the president refused.

Wilson had won a second term by only a narrow margin in 1916, and opposition Republicans regained majorities in both houses of Congress in 1918. Theodore Roosevelt, defeated for a comeback third presidential term in 1912 (in a campaign in which he once insisted on delivering a speech after he had been shot in the chest) was back in the Republican fold and, at 60 in 1918, wanted to run again.

Astonishingly, so did the incapacitated Wilson, 62. Had there been polling then — Dr. George Gallup didn’t conduct his first random sample survey until 1935 — Roosevelt would probably have been running far ahead, but he died suddenly in January 1919. Wilson, in shattered health, was persuaded to retire.

Foreign military involvement, antidemocratic demonstrations, bitter memories of the recent riots and pandemic, dismay with inflation, concern about immigration — even in the jerky film clips of that era, you can see echoes of the issues concerning American voters today.

How did the 1920 election cycle turn out? The Democrats nominated a formidable ticket: Ohio Gov. James Cox, a Dayton newspaper owner whose media conglomerate would make his heirs billionaires, and the 38-year-old FDR. But disgust with the Wilson administration weighed them down and helped elect the Republicans — Ohio Sen. Warren Harding, chosen in that smoke-filled room in Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel, and the taciturn Massachusetts Gov. Calvin Coolidge — who won by a 60% to 34% margin, the widest such margin in American history.

Such an outcome seems improbable in our current closely divided partisan politics. But voters’ concerns, echoing those in 1920, combined with Biden’s debate performance and Trump’s gallant recovery, make the Republican ticket the favorite this year, which leads to the question of what lessons the mostly successful Harding and Coolidge administrations of the 1920s have to teach today.

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and longtime co-author of “The Almanac of American Politics.”