In late May, the Durham Bulls trailed Memphis, 5-4, in the bottom of the ninth inning. With two outs, Junior Caminero took a two-strike pitch that might have been a bit outside.

No dice. The home plate umpire signaled strike three with a punchout motion. The reliever who threw the pitch clapped his hand against his glove and strode triumphantly off the mount. Game over.

Or was it? Caminero turned and faced the ump and patted his hand on his helmet.

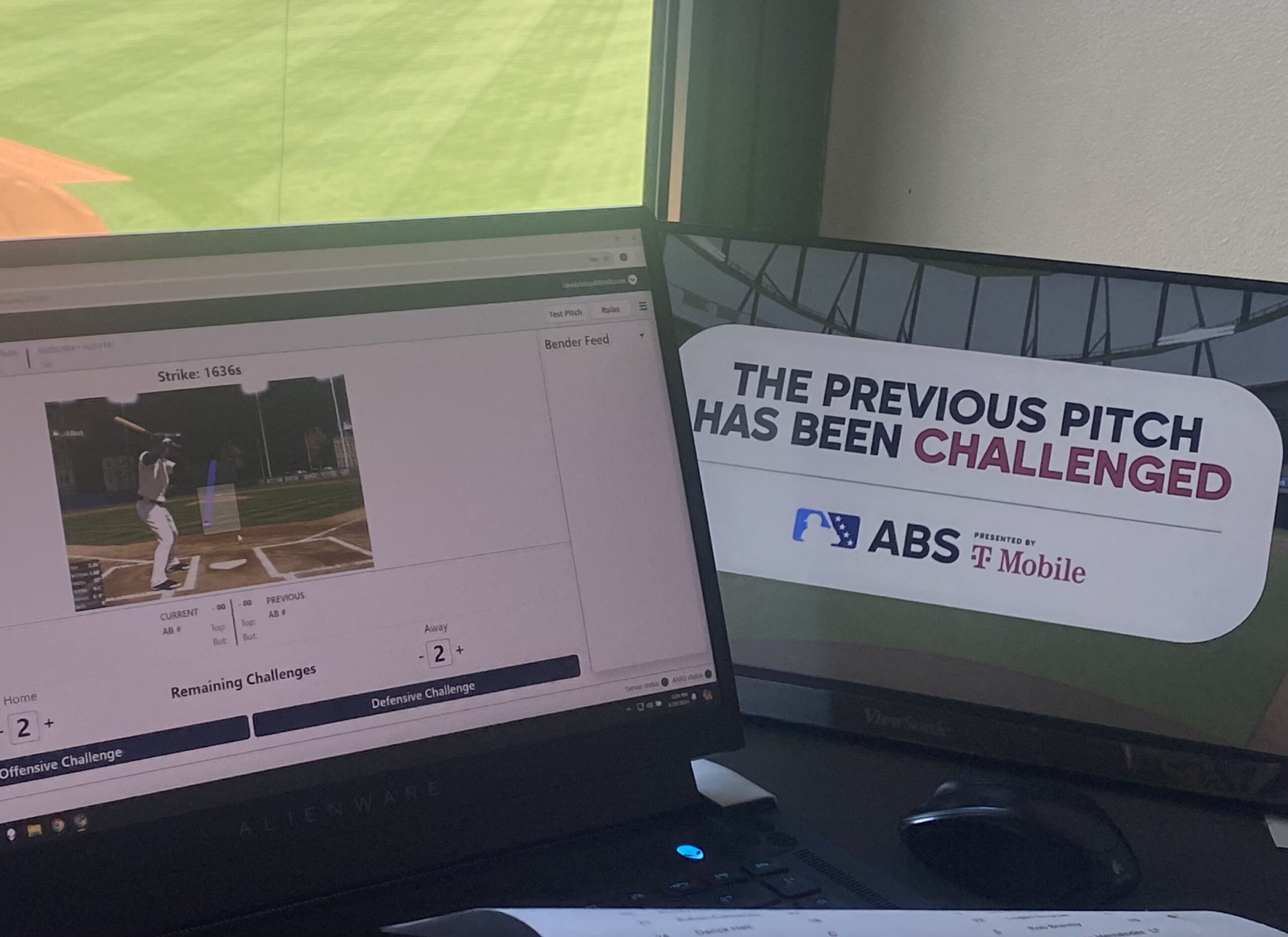

That’s when ABS took over. It stands for Automatic Balls and Strikes, but it’s better known as the Robo-Ump. It uses Hawkeye camera technology—the same thing the tennis tour uses to determine if balls are in or out—to measure the strike zone.

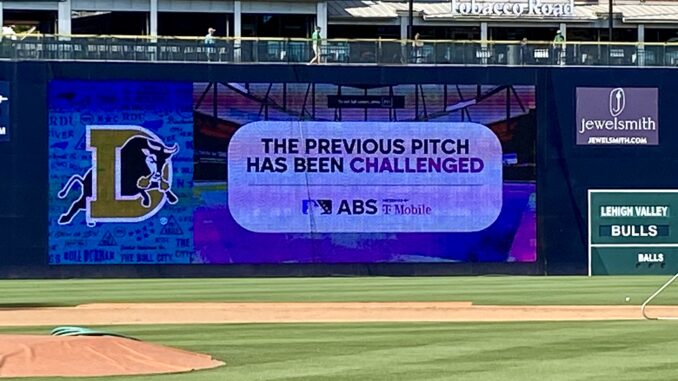

On the stadium scoreboard, a graphic showed the pitch, which drifted off the plate by a fraction of an inch. The umpire’s strike call was changed to a ball, and Caminero took his place back in the batter’s box. The crowd, energized by the unexpected drama, stopped waiting for postgame fireworks to begin and came to life.

The next pitch danced in the low and outside corner of the strike zone—or did it? The ump punched again. The pitcher stormed off the mound a second time, and Caminero again patted his helmet.

For the second straight time, he was right. Another ball, and he stepped back into the box to continue the game. The crowd noise swelled to its loudest of the day.

Two pitches later, Caminero grounded out to end things definitively. However, the back-to-back ninth-inning challenges gave a glimpse as to what we may see in MLB, perhaps as soon as 2026.

Baseball has been slowly moving toward using technology to call balls and strikes, and, much like the pitch clock that debuted in MLB last year to rave reviews, it’s been testing and tweaking the system in the minor leagues for the past few seasons.

For the last year and a half, there have been two competing systems: For Tuesday through Thursday games, the minors have used a fully automated system, where the ump got the call from ABS through an earpiece and simply reported the result with his or her call. (Note: This didn’t stop angry pitchers or batters from arguing with the umpire when they didn’t like the automated result.) On the weekends, they used the challenge system, where the umps called the game, but ABS was available for challenges.

As of last week, however, the fully automated system was put on the back burner, and all Triple-A games are now challenge games.

“I think it’s better,” said Bulls manager Morgan Ensberg, who played several years in the Major Leagues. “That it’s in the players’ hands versus just a black and white computer.”

The system adds a new level of strategy to a game that is generally slow to make big changes. Teams are limited to the number of challenges they can use. Each team had been allowed three unsuccessful challenges a game, but with the expansion of the challenge system came a reduction to two challenges losses per team per game. (Since Caminero won both of his challenges, they didn’t count against the Bulls’ total for that game.)

“You have to be a little more strategic about when you use it, since you don’t have that extra one to play with,” Ensberg said. “You’re hoping that it’s (available) during a critical part of the game.”

That’s especially crucial since the decision of when to challenge is out of the managers’ hands. They must be requested by the pitcher, catcher or batter within a few seconds of the call being made.

The minor league managers who shared their thoughts on challenges denied using a “red light/green light” system (similar to the one used for decades on stolen bases) to give certain players permission to challenge, but not others. They know who should be challenging, though.

“We tried to limit our pitchers making that call just because their heads are kind of bobbing all over the place when they’re throwing,” Contreras said, “and they’re gonna always think that they’re throwing strikes anyway.”

“(Kameron) Misner and (Austin) Shelton,” Ensberg said, mentioning the Bulls’ current home run leader, as well as someone who has spent time with the MLB Rays. “They’re very accurate. You miss by half inches, they can see it. It’s hard for people to wrap their minds around. They think it’s not possible, but it’s absolutely possible. That is the reason why they’re here. Because they really do see the ball and where it is exactly.”

If that sounds clinical and detached, that’s exactly what it takes to have a successful challenge.

“The biggest thing you got to do is not let your emotions kind of dictate the challenge call,” said Lehigh Valley IronPigs manager Anthony Contreras. “Sometimes we’ll run out of challenges, because the ones that are utilizing it just because their emotions get the best of them. They get ticked off about a call, they challenge, but they’re still wrong.”

All managers can do is remind players about when is a good—and bad—time to tap the helmet and request a challenge. And if someone chooses a bad time?

“Just make fun of them a little bit,” Contreras said. “Guys know when they do an emotional call with a challenge. They know that it got the best of them, and we’re going to make light of it and move on to the next one.”

If things continue on the current path, that next one might just be in the big leagues.