Willie Mays died last week, just before MLB was about to honor him at the special game saluting the Negro Leagues at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field.

The day after Juneteenth, baseball brought together a large group of surviving Negro League players, as well as legendary African-American MLB stars, such as Barry Bonds, Ken Griffey Jr. and Reggie Jackson, in Mays’ hometown.

It was a time to look back at the contribution made by men who, for decades, weren’t welcome on MLB fields, and Mays’ death helped add to the feeling of loss.

Countless salutes to Mays have been written and recorded in the last week. Anyone who saw him would swear that his numbers, impressive as they are, don’t do him justice. He made 24 All-Star Games, had more than 3200 hits and hit 660 home runs, which was third-most all time when he retired and is No. 6.

In fact, I realized, he now has more than 660 home runs. Mays started playing in the Negro Leagues at age 17, had a walk-off hit in the playoffs as a teenager. He logged three seasons with the Birmingham Black Barons before moving on to integrated baseball. MLB’s well-publicized decision last month to include Negro League statistics as part of the official record means that those seasons now “count”.

I headed to the record book to see what Mays’ new career total was.

660 home runs.

According to the newly integrated record book, from 1948 to 1950, Mays played a total of 13 Negro League games that are considered Major League quality. Hank Aaron, who spent part of a season with the Negro League Indianapolis Clowns before moving on to MLB, also didn’t see his home run total change, even though he reportedly hit at least five and as many as eight homers with the Clowns during his time there. None of his games count.

That’s because these seasons occurred after Jackie Robinson made his MLB debut with the Dodgers in 1947. This led to the collapse of the Negro Leagues as the talent left for integrated baseball.

So even though Mays and Aaron played in the Negro Leagues, their leagues, teams and level of competition are not considered Major League quality. So their stats still don’t count. This, despite the fact that a grand total of 11 black players set foot on MLB diamonds before the year 1950.

Now, if you took the top 11 players away from MLB today, it might lower the level of play somewhat, but it’s doubtful that it would be enough to stop considering it a major league. And, consider the fact that, despite the attrition of top players, the Negro Leagues still featured Hank Aaron and Willie Mays, as well as Ernie Banks, who spent two seasons with the Kansas City Monarchs. And, you guessed it, none of his stats count either.

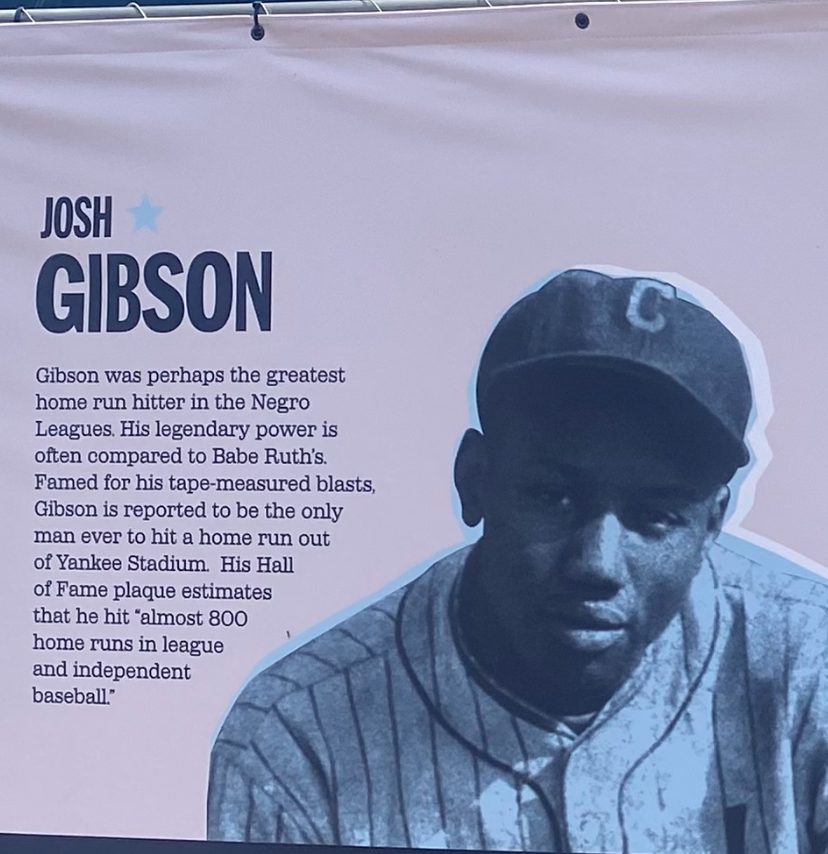

Baseball hasn’t just turned a side-eye to post-Jackie Robinson Negro Leaguers, either. Josh Gibson was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1972. Often called the “Black Babe Ruth”, Gibson’s Hall of Fame plaque in Cooperstown says that he hit “nearly 800 home runs”. Legend has it that he once hit 84 in a season. Surely, he should be at the top of the single-season and career home run lists.

Baseball Reference gives him credit for 166 home runs, never more than 20 in a season. That means that, in the official eyes of Major League Baseball, he’s more like the Black Joe Rudi.

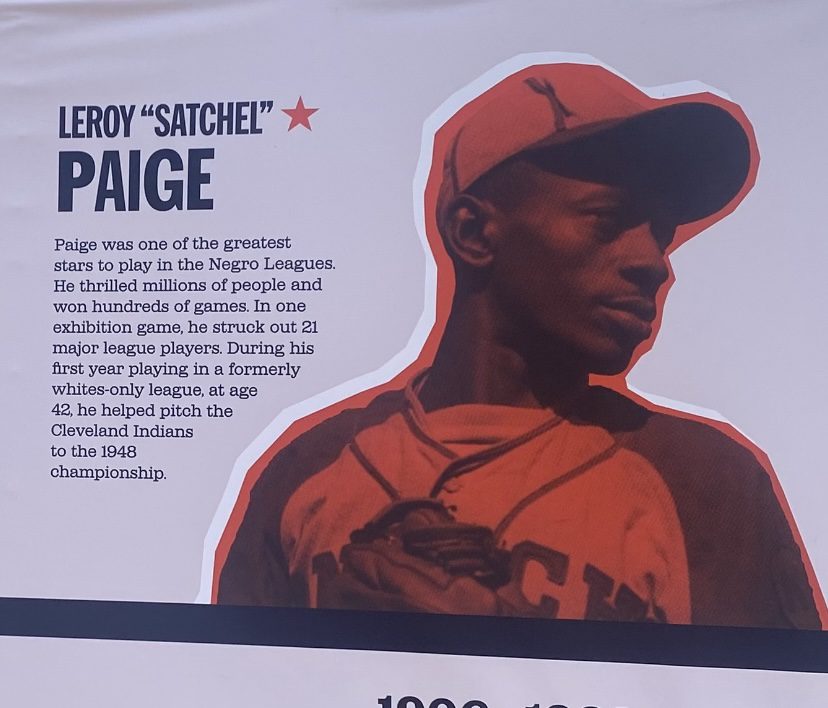

Satchel Paige’s Hall of Fame plaque said that he “won hundreds of games” in his career, which lasted from 1926 to 1965. Officially, he won 124 games that “count”. Cool Papa Bell, legend has it, once stole 175 bases in a 200 game calendar year. MLB says he had 285 steals over a 21-year career.

The problem with these career Negro Leaguers is that the Negro League seasons, the only part of the schedule that MLB recognizes, were extremely short, often 40-70 games. The bulk of the Negro Leaguers’ games were in barnstorming trips. They traveled the country, playing each other, top local teams, or all-star squads of major leaguers. And these games are considered exhibitions and ignored in the official record.

Now, to be fair, white Major League stars also went on barnstorming trips. The Bustin’ Babes (Ruth) and Larrupin’ Lous (Gehrig) traveled the country in the offseason during the 1920s. No one is arguing that their barnstorming numbers should be a part of the official record.

That’s because they have an official record. They weren’t excluded from the games that “count”. They could afford to play exhibitions. The Negro League players weren’t cashing in after a hard-fought season at their job. They were attempting to earn a living, because they were left out of the official games.

The result is lumping the MLB apples and Negro League oranges together, attempting to compare seasons of vastly different lengths. It undercuts and minimizes the accomplishments of Gibson, Paige, Mays, Banks and Aaron.

You can’t lock someone out, then say that most of what they did on the outside doesn’t count. You can’t argue, “Look who you played,” when they played the only people they were allowed to. You’re the reason that their competition was at the level it was.

If we truly want to consider Negro Leaguers as a part of major baseball, then include it all. Include the post-Jackie seasons and the barnstorming tours. It’s where they played, because there was nowhere else for them. It counted then, and it should count now.