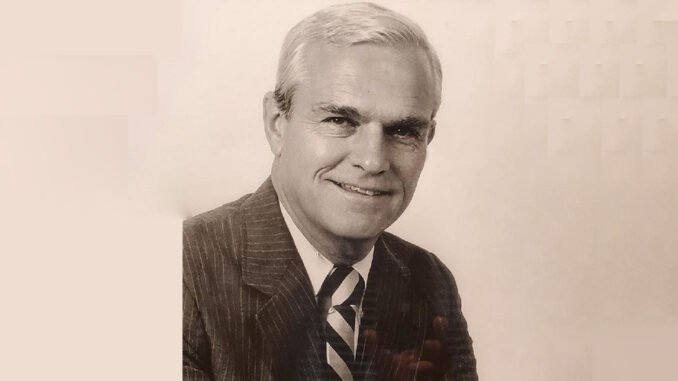

Former Congressman Alex McMillan passed away April 19 at age 91.

To those who knew him, he was a great friend. He was one of the last true statesmen from an era when serious people went to Congress to get serious things done ― and then go back home to lead normal lives.

To me, he was my boss who became my mentor, instructor, role model, big brother/father figure and friend. He was the epitome of a citizen-politician who left his role as CEO of Harris-Teeter Supermarkets at age 52 to run for Congress. He didn’t have to leave such a prestigious job to join the Republican minority party in the House which had held little power since 1952 ― but he did.

When I asked him why he did it, he replied without any sense of egotism or pomposity: “It never occurred to me NOT to run”. He came from the generation whose fathers and older brothers fought in World War II. A sense of public service was not a frivolous option but a matter of personal honor and duty.

He won by a scant 321 votes in 1984 to join the Republican minority in Congress during the second Reagan administration. He served during the George H.W. Bush 41 term but retired having never served in the majority before Republicans took control of Congress in the tidal wave of 1994.

However, everyone in Congress knew who Alex McMillan was. Democratic staff directors told me McMillan was the one person their side was most afraid of simply because he knew far more about everything in the business world than they and their bosses did, including powerful chairmen such as John Dingell, Henry Waxman and Leon Panetta. We, as his staff, hardly ever had to write questions for him to ask in hearings because he knew what he wanted to ask and didn’t need our input.

It was the exercise of political power in the purest sense in our democratic republic ― using reason, experience and facts to persuade people with civil discourse. He understood what it took to work with Democrats to get to 218 votes in the House ― a rare talent that has disappeared from Congress for most of the 21st century.

He didn’t sign pledges. He knew they would hamstring his efforts to forge the very compromises he knew were the foundation of our representative democracy since inception. The only oath he took was to support and defend the Constitution on the first day of each new Congress. He didn’t clamor to get on TV ― there were show horses who never saw a camera or microphone they didn’t speak into, but he preferred to be a workhorse doing the hard work behind the scenes.

The amazing thing was that he was able to do it without forfeiting his values of decorum, dignity and his legendary dry sense of humor. A person could disagree with him on an issue, but he was such a Southern gentleman and so likable as a person they could not dislike him. He was widely respected on both sides of the aisle.

He was part of the negotiating team at Andrews Air Force Base which produced the seminal Budget Agreement of 1990 that set the stage for controlling spending for the next decade. As the second-ranking Republican member of the House Budget Committee, he called for specific line-item spending reductions in the 1993 “Cutting Spending First” Republican budget alternative which simply had never been done in such a political setting. When the bulk of these recommendations were included in the 1997 Balanced Budget Act signed by President Bill Clinton, the federal budget was not only balanced for the next four years but more than $600 billion of national debt was paid off and retired due to recurring budget surpluses.

He made his mark as a statesman by voting in the best interests of the country first and virtually ignoring his personal political prospects. He could talk about the intricacies of a telecom reform bill or textile legislation during a legislative briefing and then shift easily into lengthy expositions about Thomas Jefferson, Winston Churchill and the Civil War. One of his favorite subjects was the complicated yet brilliant Alcibiades, which sent us all to our history books to learn more about the Peloponnesian War.

He loved his wife, Caroline, and family dearly and foremost. Alex and Caroline made everyone feel like part of their extended family. Alex McMillan must have dozens of people who can claim him as their godfather because their parents respected him so much, including our first son.

He helped form The Institute for the Public Trust which I now run. In each class during the first session, I tell them about Alex McMillan and how we are looking for great people to run and serve “in the public trust” just as he did.

He wanted to serve his country, and he did it well.