An increasing number of Americans are asking whether our Constitution is obsolete.

Whether that fear leads to legal cynicism, political despair or a call for radical change varies from person to person, but the question is a real one and worth careful thought, for two reasons. The common life of the United States centers on the U.S. Constitution to a degree unparalleled elsewhere, and if that center is out of date, we have a serious problem. And ours is the oldest national constitution in the world: It isn’t implausible to think, or at least worry, that it no longer serves our national needs.

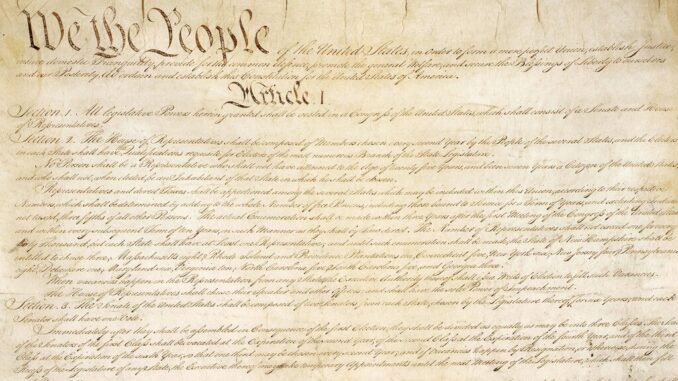

The main body of the Constitution was written 237 years ago, and our Bill of Rights (the first 10 amendments) a couple of years later. They were written in and for a world without photography, telecommunications, practicable steamships, trains, cars, electric lights or nuclear weapons. The United States was a predominantly rural, pre-Industrial Revolution society with fewer than 4 million inhabitants, over 17% of whom were enslaved.

The framers and ratifiers were all white men, and almost all the leading figures were “gentlemen” who assumed that political leadership naturally belonged to the propertied class. While most of the founders conceded, theoretically, that human slavery was morally wrong, the vast majority thought black Americans inferior and simply hoped that the slavery problem would go away on its own, without disturbing anyone’s pocketbook.

As far as we know, none of the framers or ratifiers objected to excluding women from political life. It would be surprising if a Constitution devised by men of such views, in so different a time, was not obsolete.

Worry that the Constitution is outdated isn’t based solely on such considerations: a variety of its specific features seem to demonstrate the Constitution’s obsolescence. I will mention three. First, the process of national lawmaking is slow and cumbersome, requiring majority support in both houses of Congress, and even then legislation can be thwarted if the president vetoes a bill and a minority in either house agrees. Second, the president is thought to wield too much unilateral power over U.S. foreign policy and the use of military force, leading to endless foreign wars and (potentially) nuclear conflict with little congressional or popular control. Third, the federal courts play too great a role in American life, making public policy on sensitive issues regardless of public sentiment. The list could go on indefinitely.

There is considerable truth in these worries, but I nonetheless reject the conclusion that the Constitution is obsolete. Look again at the three specific concerns I just mentioned. Yes, the Constitution creates a process with built-in checks on successful lawmaking. But that’s not an unanticipated bug in the system: It is instead an intentional choice by the founders, who sought to create a Congress that would have the powers and flexibility to meet national needs but only when and to the extent that legislation has wide public support.

The Congress of 2024 is prone to deadlock because we the people are so evenly divided on so many issues. American history provides repeated proofs of the ability of Congress to act, decisively, when a true national majority wants it to.

I agree that modern presidents — every president of either party — have grown too accustomed to treating American foreign policy as their exclusive domain, and too prone to resort to military force in pursuing whatever goals they think appropriate. Here too, however, we the people are ultimately responsible. Congress has ample power — over spending, foreign commerce and the armed forces — to limit unilateral presidential action. If Congress fails to do so, who is it that puts those feckless senators and representatives in office in the first place?

And what about the courts? The federal courts have shown themselves quite willing to act on a remarkable (and I think over-broad) range of issues. This is by no means all our fault. Federal judges aren’t elected, life tenure insulates them against personal consequences for controversial or ill-reasoned decisions, and few make it to the Supreme Court in particular without developing some degree of hubris.

But here too, we the people have played a critical role. Precisely because we are so polarized, Americans on both sides of many issues have largely given up trying to persuade their fellow citizens and have turned instead to seeking victory in, and often by packing, the courts. If we ask less of our courts and more of ourselves, there is reason to hope the judges will display more modesty in decision.

By now you have probably guessed my broader reason for denying that the Constitution is obsolete. The founders weren’t infallible, and we can and should disagree with them on a host of vital issues. But the Constitution they created is above all else a structure carefully designed to subject those who govern to the will of the governed and to require government to defend its actions at the bar of popular opinion as well as in the courtroom.

All American citizens ought to view it as their duty to be politically involved, to vote and to consider stepping forward to run for office themselves so that service in elected positions is truly shared among the people rather than the preserve of professional politicians.

If we do, no one will have reason to worry that the Constitution is obsolete.

Jeff Powell teaches constitutional law at Duke University Law School.