In an era where analytics are as much a part of scouting as film breakdown, there are plenty of numbers for NC State to crunch heading into Friday’s Sweet 16 game against Marquette.

The Golden Eagles have an offensive rebounding rate of just 25.8%, one of the worst among power conference teams. Guard Tyler Kolek takes 18% of his shots from midrange, a rate nearly double that of teammate Kam Jones. And sundown in Dallas comes at 7:46 PM Central Time.

That last statistic may seem more like an interesting tidbit thrown in at the end of the weather report on a local station, right after dew point and pollen levels. However, it’s critically important for one member of the Wolfpack and will be monitored closely throughout the waning moments of the second half, likely as the game hits crunch time.

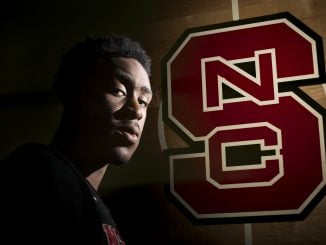

NC State junior forward Mohamed Diarra is a practicing Muslim. This season, the holy month of Ramadan falls during the college basketball season. The past few years, when Diarra played at Garden City Community College and then Missouri, Ramadan started in April, after his season had ended. This year, however, it started on March 10, two days before NC State’s first game in the ACC Tournament.

Ramadan requires Muslims to observe a strict fast, from sunup to sundown. They cannot eat or drink—even water—during daylight hours.

“I’m used to it,” Diarra said. “I’ve been doing it since I was 12 years old, so I’m prepared for not eating or drinking anything. I know what I’m doing.”

Still, for the last seven games, Diarra has had to change his gameday routine to accommodate his fast. State’s ACC Tournament opening game tipped off at 4:30, nearly three hours before sundown. So Diarra wasn’t able to eat or drink at all during the game.

“Sometimes that happens,” he said. “Sometimes, I know during the game I’m not able to eat. (Friday’s) game is at 6 (6:09 Central time, more than an hour and a half before sundown). So, I know—I don’t eat. I can make it all game, if I prepare in my mind, ‘Okay, get ready for this game. You can’t eat or drink.’”

Since that first game, he’s had three games that started after sundown, meaning he could take water breaks, and three that were like Friday’s Marquette contest will be, where his fast extends through part of the game.

It’s a delicate dance that involves the coaches, managers and team nutritionist Jesse McGinley watching the clock and preparing a midgame meal as soon as the sun drops below the horizon.

“Usually, I’m just in the game, playing my game, when they say it’s time,” he said. “Sometimes, I’ll say, ‘What time is it? I’m getting hungry,’ and they’ll say, ‘Oh, you have five minutes left. … You’ve got two minutes left.’”

Once the magic hour hits, McGinley leaps into action. She’ll prepare a nutritional paste for him to suck down with his first cup of water in 14 hours. Then he’ll quickly eat a banana. If a time out didn’t happen to synch up with sundown, Diarra will then head back to the scorer’s table to check back into the game.

That may not seem like much of a meal, but breaking the fast can be as hard on the body as going without.

“When you don’t eat all day, and then you start, you have to eat just a little bit, drink a little bit,” he explained. “You don’t want your stomach to cramp. So I’ll have a little bit. An hour later, maybe I’ll have a little bit more.”

Diarra’s big meal is a pre-dawn breakfast at 5:30.

“I’ll eat a lot then,” he said.

So far, the fast hasn’t seemed to hurt Diarra’s production on the court. He’s playing more minutes (32.3 per game), averaging more rebounds (12.1 per game) and scoring more points (10.6) than he was when he could eat or drink whenever he wanted.

Technically, according to Muslim law (at least as explained on the internet), Diarra doesn’t have to go through all of this. One of the valid exemptions from the Ramadan fast is for travelers, which is defined as a trip lasting longer than three days and taking the Muslim more than 50 miles from home. Since State has gone from Raleigh to Washington, D.C., Pittsburgh and now Dallas for their postseason run, Diarra would be justified in having a cup of Gatorade while playing college basketball at the highest level. He chose not to take that exemption, however, and to observe the fast.

That doesn’t mean the temptation hasn’t been there as he runs up and down the floor, banging bodies with seven footers. If he has a sip of water during a time out or takes a bite of a protein bar, no one would know or hold it against him.

“Sometimes (I’m tempted),” he said. “But, actually, no, I can’t do it. I can’t quit right then. I’ve done it all day. I can’t quit with an hour or 15 minutes left.”

Ramadan will end on Tuesday, April 9, the day after the national championship game. Diarra is more than willing to continue his balancing act until then. You might even say he’s hungry for a title.