You could blame Victor Hugo. In 1846, the French novelist observed a young man being arrested for holding a loaf of bread he stole.

Deeply touched, he fashioned his novel “Les Miserables,” published in 1862, around the character Jean Valjean, who is imprisoned for 19 years for stealing a loaf of bread and pursued relentlessly after his release by Inspector Javert.

You may have followed the story, sort of, in the musical “Les Mis,” which began its run in Paris in 1980 and London in 1985. Or you may have heard the quip by the later French writer Anatole France that “the law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal their bread.”

Curiously, some people, even in the United States in the 21st century, seem to think that the conditions Hugo and France described in their fiction still prevail here — even though their relevant writings were set nearly 200 years in the past, and no one without severe mental handicaps goes hungry today for want of bread in countries such as France and the U.S.

But the assumption persists that if someone steals, particularly if someone steals items worth small amounts of money, that person must be in dire want or acting to help someone who is. Didn’t Karl Marx and others of Hugo’s generation teach that mankind acts always and everywhere primarily out of economic motives?

Something like this line of thought, perhaps without the literary references, explains the laws decriminalizing the thefts of items worth small amounts of money. Primary examples include California’s law, passed in a referendum in 2014, raising from $400 to $950 the amount of shoplifted goods justifying a felony prosecution.

Similarly, in New York state, stealing property worth less than $1,000 is a misdemeanor. So prosecutors, many financed by the left-wing billionaire George Soros, in these two large states and elsewhere have effectively decriminalized shoplifting.

Proposition 47 was pitched as a measure to relieve prison overcrowding and defended by an Associated Press reporter as not preventing misdemeanor prosecutions of those filching goods worth $949 or less. But of course, that’s not what happened.

Instead, shoplifting has become a mass, and scary, phenomenon, encouraged by organized criminals who resell stolen merchandise.

Those who see low-dollar shoplifters as 21st-century Jean Valjeans should realize that theft is not necessarily a nonviolent crime and that low-value theft losses can inflict severe damage on those with modest incomes.

It’s like what Jack Maple, an architect of New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s police reforms, concluded when told that burglaries of under $10,000 weren’t investigated in Manhattan. “If you were Donald Trump and had a painting taken,” he recalled, “we would have 30 … cops there. If you’re poor, you could have your life savings stolen from you, and nobody was going to investigate it, which is outrageous! I just saw what the rule was, and I changed it.”

In most cases, the flash mobs swarming into chain drugstores and bodegas in Manhattan and San Francisco, invariably ignored by uniformed security and police officers, don’t take much directly from customers. But they do put people just going about their daily lives in fear of injury or death, the common law definition of assault, and increase the cost and availability of goods in their neighborhoods.

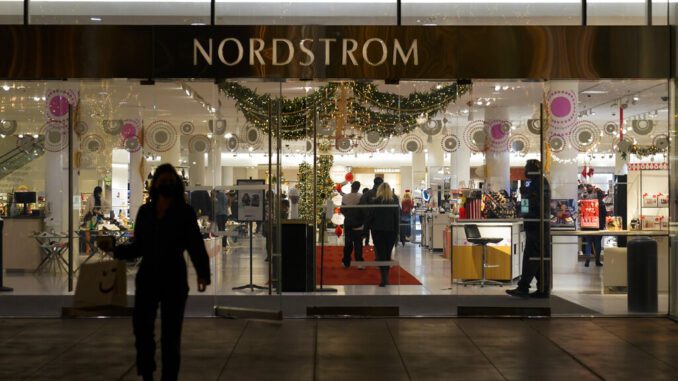

So chain drugstores place under lock and key razor blades and toothpaste and shampoos, which can be sold to organized gangsters who sell them at low prices with no sales tax. Other stores just close, such as Nordstrom on San Francisco’s Market Street and CVS branches in Midtown Manhattan.

In southeast Washington, D.C., Giant Foods has removed brand-name merchandise from its supermarket (store brand items apparently aren’t fencible).

That’s supported by local Councilman Trayon White (last seen blaming the Rothschilds for a heavy snowfall), who reports that Giant’s shoplifting loss is 20% of sales and says that, without changes, the store, the only one in the neighborhoods, will close.

It’s an uncomfortable and rarely reported fact that the large majority of shoplifting mobs are young black men, some of whom may believe they’re redressing Jean Valjean-type grievances. White disagrees. “We know it’s tough times, and we know the price of food has skyrocketed in the last three years,” he said. “But we cannot afford to hurt ourselves by constantly taking it out of the store.”

In saying so, he shows an appreciation of the inevitable result of effectively decriminalizing stealing that evidently evaded sophisticated New York state legislators and the 60% of California voters who voted to do so. As the statement often attributed to San Francisco longshoreman/philosopher Eric Hoffer about 50 years ago says, “Every great cause begins as a movement, becomes a business, and eventually degenerates into a racket.”

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and longtime co-author of “The Almanac of American Politics.”