Walter Royal, the chef of a destination steakhouse in North Carolina who triumphed as a challenger on “Iron Chef America” by cooking mostly Southern dishes with ostrich meat, has died.

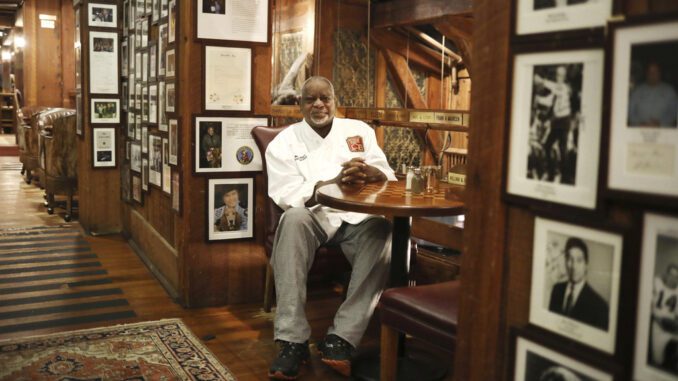

The Angus Barn in Raleigh, where Royal served as executive chef since the 1990s, announced his passing on its website. The restaurant’s statement said Royal died Monday at the age of 67. The announcement did not provide a cause or say where the chef had died.

The grandson of farmers, Royal grew up in rural Alabama and worked as a social worker before honing his craft under acclaimed Southern chefs, The Raleigh News & Observer reported.

Royal was already well established as a chef in the Raleigh area when he cooked before a national audience in a 2006 episode of “Iron Chef America.” Judge Joel McHale said Royal used one of the world’s “ugliest birds” to create one of the best desserts. It was a chocolate soufflé made with an ostrich egg.

Royal led a team challenging celebrity chef Cat Cora in a kitchen stadium format where their “secret ingredient” turned out to be ostrich. The trick, he said, was not to overcook it.

Royal prepared a Southwestern-flavored ostrich burger with horseradish ketchup, Creole mustard and homemade potato chips, according to a 2007 News & Observer article. Other dishes included a soy-and-ginger ostrich satay rounded off with a peanut dipping sauce and spicy coleslaw, and a pot pie with ostrich cubes and an herbed puff pastry.

He enhanced the meat’s flavor with a rich whiskey-shallot-ostrich broth reduction, serving wilted watercress and mashed turnips and rutabagas on the side.

Regarding the soufflé, Royal told The Fayetteville Observer: “The yoke of the egg is almost like butter. It’s just incredible and the consistency of a wonderful custard.”

Royal was born in Eclectic, Alabama, about 30 miles northeast of Montgomery, according to his biography on the website for The National Association of Chief Executive Officers.

In a 2017 interview with the North State Journal, Royal recalled a childhood of eating pecan pie, country cured ham with a glaze, fresh turkeys from his grandparents’ farm and apple cobblers that were “oh, divine.”

Royal knew he wanted to cook professionally since he was 14. But his parents dissuaded him, unsure of how successful he would be as a Black chef, according to the national chief executive biography. He got psychology degrees from LaGrange College in Georgia and Auburn University, where he did his graduate work.

He worked with children with mental disabilities for five years before heading off to Atlanta to study at Nathalie Dupree’s Cooking School.

“For me, it wasn’t just loving the cooking, it was the farming and growing of animals. It was one total package,” Royal told The North State Journal. “But my parents weren’t going to let me be a farmer without an education and you know what? They were a 1,000 percent right. The better prepared in your mind, the more successful you’re going to be.”

At the Angus Barn, an upscale steakhouse in Raleigh, Royal said his psychology background helped him work with a staff of more than 200 at a restaurant that served 600 guests a night and prepared about 11,000 pounds of meat a week, according to a 2000 interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

For his last meal, he told the newspaper: “I could probably draw that out for several years, but for one final meal, I’d like roast chicken with roasted garlic mashed potatoes and green beans and a big, buttery chardonnay.”