Last week Frank Hill published a column, “When does education become indoctrination?” In part, his essay is a lament that the UNC faculty has forgotten they are state employees (and who pays the bills). UNC professors, and by implications many more, are disparaged for their haughtiness of wanting to control the curriculum they teach.

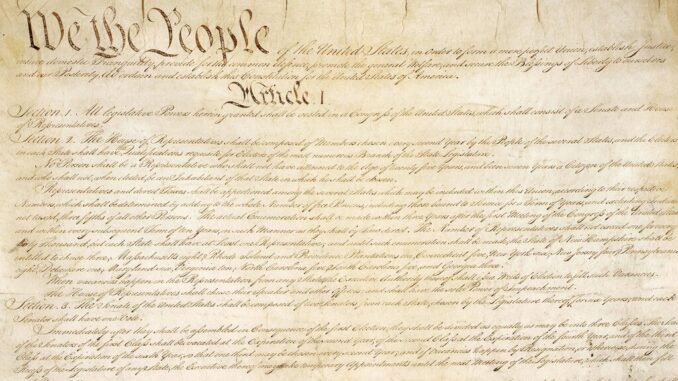

More fundamentally, however, his essay is an affirmative piece, crying out that our country not lose our shared Constitutional inheritance.

Recently I collaborated with a South Sudanese immigrant in preparation for the high school equivalency exam. Consistent with the curriculum, we talked long sessions on the Constitution. My appreciation for the U.S. Constitution was refreshed and I again fell in love.

I embrace the basic tenets of Hill’s sonata, that a shared affinity for the Constitution’s elegance is the glue for our governance. The collateral damage in the essay, however, seems to be college faculty, and, as I see it, similarly state legislators.

The very existence of the Professor/Legislature standoff is an example of “Checks and Balance” at work.

College professors are admonished for allowing only their ideology to be in the lecture hall. Lest we forget, professing is indoctrination. And as he states, so too are everyone’s messages.

He alludes to the existence of “pure education,” presumably some ideal outside the realm of indoctrination. I have no idea what that means, presumably some former gold standard for what citizenship meant, but more likely is that which agrees with one’s own ideology.

You do not have to be much of a historian to realize a pure conception of constitutionalism has never existed in this country. The country’s entire history is a contest over the Constitution’s meanings.

All Constitutional talk is indoctrination, including everyone’s classes or legislative rules.

It’s just a matter of who gets to decide.

I reach a quandary when contemplating who should decide what is indoctrination.

My lived experience is that most people I include in my life, my “too liberal” and “too conservative” friends, are invariably reasonable people. Their views on most issues are much more nuanced and far-sighted than the political pap offered to fire them up for the next election.

I am confident a visit with the 677 “politically tin-eared” UNC professors would solicit scores of nuanced reasons, many, if not most, would make sense, hardly an imposing danger. The same would be true if you visited with the legislative majority. They would often make sense, considerably less belligerence than the media might convey.

The debate is less about ideas and more about who controls. Faculties are right to be afraid of others telling them what to do (a world mandated by the Florida legislature). And the legislature should attend to the “colossal power” of a few disparate and careless voices undermining social cohesion.

My takeaway from my 50 years in higher education is that however much we think we are influencing our students, what we teach is overwhelmed by background and life, family and circumstance. The people we know in our lives have not been destroyed by the professor’s prophecies. Most simply carry on.

I conjecture too that legislative “overreach” is not as big a threat as presented. Institutional systems, regardless of regulations, tend to seek their own stasis and are hard to move, perhaps harder than changing the “Washington swamp.”

The left often sees professors as a societal safeguard stemming an inevitable historically authoritarianism strain. Yet their collective certainty becomes its own censorship, most easily identified currently as “Cancel Culture.” The Right becomes the self-appointed protector of the vulnerable from the well-meaning but dangerously wrong intelligentsia.

Anti-intellectualism is not new. When it goes too far, professional and educated classes are provided residency in a gulag.

As the threat is largely invented, I would have no problem with someone requiring classwork in the Constitution. After all, schools add requirements for students all the time. Requiring students to learn the Constitution, a collective understanding governance, seems sensible.

Currently in our divided cultures “who decides” becomes the energized political base, the most opinionated constituents. This reductionist point of view casts the professors as ingrates and the legislators as bullies. Yet neither resembles a monolith.

Adding constitutional law classes seems reasonable enough. Telling instructors what they can profess about the Constitution is wholly another matter.

Allan Louden is a communication professor emeritus at Wake Forest University.