Twenty-six words tucked into a 1996 law overhauling telecommunications have allowed companies like Facebook, Twitter and Google to grow into the giants they are today.

A case coming before the U.S. Supreme Court this week, Gonzalez v. Google, challenges this law — namely whether tech companies are liable for the material posted on their platforms.

A second case, Twitter v. Taamneh, also focuses on liability, though on different grounds.

The outcomes of these cases could reshape the internet as we know it. Section 230 won’t be easily dismantled. But if it is, online speech could be drastically transformed.

WHAT IS SECTION 230?

If a news site falsely calls you a swindler, you can sue the publisher for libel. But if someone posts that on Facebook, you can’t sue the company — just the person who posted it.

That’s thanks to Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, which states that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

That legal phrase shields companies that can host trillions of messages from being sued into oblivion by anyone who feels wronged by something someone else has posted — whether their complaint is legitimate or not.

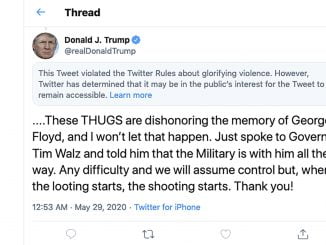

Politicians on both sides of the aisle have argued, for different reasons, that Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms have abused that protection and should lose their immunity — or at least have to earn it by satisfying requirements set by the government.

Section 230 also allows social platforms to moderate their services by removing posts that, for instance, are obscene or violate the services’ own standards, so long as they are acting in “good faith.”

The measure’s history dates back to the 1950s, when bookstore owners were being held liable for selling books containing “obscenity,” which is not protected by the First Amendment. One case eventually made it to the Supreme Court, which held that it created a “chilling effect” to hold someone liable for someone else’s content.

That meant plaintiffs had to prove that bookstore owners knew they were selling obscene books, said Jeff Kosseff, the author of “The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet,” a book about Section 230.

A few decades later, as commercial internet was taking off, politicians revisited this legal question, worried about discouraging newly forming internet companies moderating content, and Section 230 was born.

“Today it protects both from liability for user posts as well as liability for any claims for moderating content,” Kosseff said.

Broadly, there are two possible outcomes if Section 230 is eliminated. Platforms might get more cautious, as Craigslist did following the 2018 passage of a sex-trafficking law that carved out an exception to Section 230 for material that “promotes or facilitates prostitution.” Craigslist quickly removed its “personals” section, which wasn’t intended to facilitate sex work, altogether.

Another possibility: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and other platforms could abandon moderation altogether and let the lowest common denominator prevail.

Any change to Section 230 is likely to have ripple effects on online speech around the globe.

“The rest of the world is cracking down on the internet even faster than the U.S.,” Goldman said. “So we’re a step behind the rest of the world in terms of censoring the internet.”