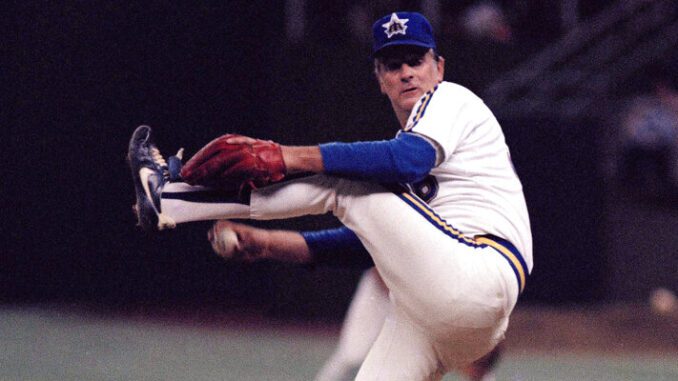

GAFFNEY, S.C. (AP) — Baseball Hall of Famer and two-time Cy Young Award winner Gaylord Perry, a master of the spitball and telling stories about the pitch, died Thursday. He was 84.

Perry died at his home in Gaffney at about 5 a.m. Thursday, Cherokee County Coroner Dennis Fowler said. He did not provide additional details. A statement from the Perry family said he “passed away peacefully at his home after a short illness.”

The native of Williamston made history as the first player to win the Cy Young in both leagues, with Cleveland in 1972 after a 24-16 season and with San Diego in 1978 — going 21-6 for his fifth and final 20-win season just after turning 40.

“Before I won my second Cy Young, I thought I was too old — I didn’t think the writers would vote for me,” Perry said in an article on the National Baseball Hall of Fame website. “But they voted on my performance, so I won it.”

“Gaylord Perry was a consistent workhorse and a memorable figure in his Hall of Fame career,” MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement, adding, “he will be remembered among the most accomplished San Francisco Giants ever … and remained a popular teammate and friend throughout his life.”

Perry was drafted by the San Francisco Giants and spent 10 seasons among legendary teammates like Hall of Famer Willie Mays, who said Thursday that Perry “was a good man, a good ballplayer and my good friend. So long old Pal.”

Juan Marichal remembered Perry as “smart, funny, and kind to everyone in the clubhouse. When he talked, you listened.”

“During our 10 seasons together in the San Francisco Giants rotation, we combined to record 369 complete games, more than any pair of teammates in the major leagues,” Marichal said. “I will always remember Gaylord for his love and devotion to the game of baseball, his family and his farm.”

Perry, who pitched for eight major league teams from 1962 until 1983, was a five-time All-Star who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1991. He had a career record of 314-255, finished with 3,534 strikeouts and used a pitching style where he doctored baseballs or made batters believe he was doctoring them. North State Journal named him Martin County’s all-time best athlete in 2020.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame said in a statement that Perry was “one of the greatest pitchers of his generation.” The Texas Rangers, whom Perry played for twice, said in a statement that the pitcher was “a fierce competitor every time he took the ball and more often than not gave the Rangers an opportunity to win the game.”

“The Rangers express their sincere condolences to Gaylord’s family at this difficult time,” the team’s statement said. “This baseball great will be missed.”

Perry’s 1974 autobiography was titled “Me and the Spitter,” and he wrote it in that when he started in 1962 he was the “11th man on an 11-man pitching staff” for the Giants. He needed an edge and learned the spitball from San Francisco teammate Bob Shaw.

Perry said he first threw it in May 1964 against the New York Mets, pitched 10 innings without giving up a run and soon after entered the Giants’ starting rotation.

He also wrote in the book that he chewed slippery elm bark to build up his saliva, and eventually stopped throwing the pitch in 1968 after MLB ruled pitchers could no longer touch their fingers to their mouths before touching the baseball.

According to his book, he looked for other substances, like petroleum jelly, to doctor the baseball. He used various motions and routines to touch different parts of his jersey and body to get hitters thinking he was applying a foreign substance.

Giants teammate Orlando Cepeda said Perry had “a great sense of humor … a great personality and was my baseball brother.”

“In all my years in baseball, I never saw a right-handed hurler have such a presence on the field and in the clubhouse,” Cepeda added.

Seattle Mariners Chairman John Stanton said in a release that he spoke with Perry during his last visit to Seattle, saying Perry was, “delightful and still passionate in his opinions on the game, and especially on pitching.”

Perry was ejected from a game just once for doctoring a baseball — when he was with Seattle in August 1982. In his final season with Kansas City, Perry and teammate Leon Roberts tried to hide George Brett’s infamous pine-tar bat in the clubhouse but was stopped by a guard. Perry was ejected for his role in that game, too.

After his career, Perry founded the baseball program at Limestone College in Gaffney and was its coach for the first three years.

Perry is survived by wife, Deborah, and three of his four children in Allison, Amy and Beth. Perry’s son Jack had previously died.

Deborah Perry said in a statement to The AP that Gaylord Perry was “an esteemed public figure who inspired millions of fans and was a devoted husband, father, friend and mentor who changed the lives of countless people with his grace, patience and spirit.”

The Hall of Fame’s statement noted that Perry often returned for induction weekend “to be with his friends and fans.”

“We extend our deepest sympathy to his wife, Deborah, and the entire Perry family,” Baseball Hall of Fame chairman Jane Forbes Clark said.