According to family lore, Evan Perry turned down the chance to play minor league baseball because his family needed him to help work on their farm. He eventually inherited the 25-acre tobacco, corn and peanut farm, and decided to let his sons take the chance he couldn’t afford to — a decision that helped lift him, and the farm, out of debt for the first time.

One of those sons, Hall of Fame pitcher Gaylord Perry, passed away last week at age 84. He was the last living Hall of Famer out of the seven North Carolina has sent to Cooperstown — Luke Appling, Rick Ferrell, Catfish Hunter, Buck Leonard, Enos Slaughter and Hoyt Wilhelm are the others — and his journey to the highest levels of his sport had roots in his family’s Martin County farm.

Gaylord began working on the farm, along with his older brother and fellow MLB player Jim, at age 7. His father always left room for baseball, however, allowing his sons to play on the school team and joining them in semi-pro leagues in the area.

“As I think about the passing of my brother, I am reminded of the many good times we shared,” Jim Perry said in a statement released by Campbell University. Both brothers attended the school, although Gaylord never played for the Camels, attending in between minor league seasons. “Growing up together on the farm, we made up a homemade ball and learned the game of baseball playing with our dad during noontime breaks from picking tobacco.”

Gaylord was on the football, basketball and baseball teams at Williamston High School. Perry starred in all three sports, getting named All-State twice in football and averaging 30 points and 20 rebounds on the hardwood.

But it was clear early on that Perry’s future was on the mound. He starred for the high school team, and as a freshman, he and Jim threw shutouts on back-to-back days to win the best-of-three series for the state title. He would go on to post a record of 33-5 and attract a large number of scouts to the area.

Parker Chesson, at the time a star pitcher for Perquimans High, remembers facing Perry in a mound matchup between the two schools. In an essay he wrote for the book “Baseball in the Carolinas” he recalls his impression of the future Hall of Famer.

“Gaylord, who was a year older than me, and I were both pitchers who played other positions when not on the mound,” he recalled. “Unfortunately, the similarities stopped pretty much there. … At 6’4” and about 200 pounds, he was an imposing figure, and he had a blazing fastball. Talent wise, he was in another league.”

Chesson said that his high school principal approached him on the day he was facing Perry in a game and said that several MLB scouts had called the school asking for directions to the field.

“Maybe this will be a chance to show your stuff,” the principal told him. Chesson joked that the scouts were only interested in one man, however, and that the scout running a video camera took breaks when Perry wasn’t on the mound. For his part, Perry struck out 15 in the game, prompting Giants official Tom Sheehan to tell area scout Tim Murchison, “You better make arrangements to sign that boy.”

The Giants did just that, signing Perry for $70,000. He spent a decade with the team and another 12 years in MLB with eight other teams. He became the first pitcher to win the Cy Young Award in both leagues, winning with Cleveland in 1972 and San Diego in 1978. He was also a five-time all-star, threw a no-hitter in 1968 and finished with 314 wins and 3,534 strikeouts. Those rank 17th and eighth all-time in MLB history.

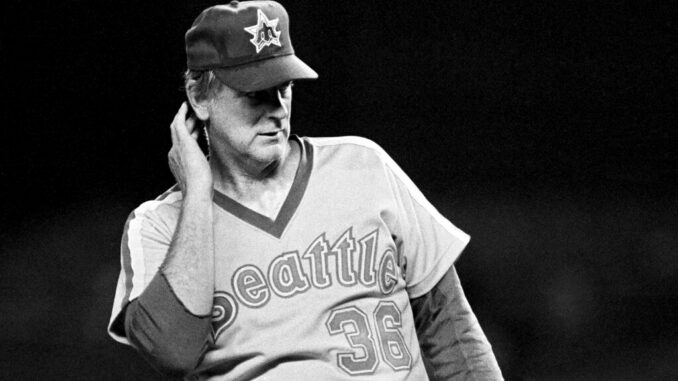

Perry is best known for his long-suspected habit of throwing an illegal spitball. He wrote an autobiography in 1974 titled “Me and the Spitter,” and by the end of his career had a prolonged routine of touching various areas of his cap and uniform before throwing a pitch, pretending he was accessing some hidden illegal substance to load up the ball.

In his early days in North Carolina, however, he was farm-boy strong and certainly didn’t need any help from illicit means to mow down batters.

“He is the most famous athlete to come out of our area,” Riverside athletic director Phil Woolard told local TV station WITN. “We’ve had a lot, but he had the longest career. He was a guy that we measure pitchers in Martin County by.”

The good-natured sense of humor that Perry exhibited in his late-career act on the mound was evident in the early days, however.

Former Williamston tourism director Barney Conway grew up with Perry and told the station, “His name will go down in history. He was probably the best-known pitcher around. He had a good attitude about baseball. He had a good attitude about life. He had a good attitude about people. He was just a good person to be around.”