DES MOINES, Iowa — The Hy-Vee Hall ballroom in Des Moines erupted in cheers in 2008 when the youthful Illinois senator hinted at the improbable possibility of the feat ahead: “Our time for change has come!”

That Iowa, an overwhelmingly white state, would propel Barack Obama’s rise to become America’s first black president seemed to ratify its first-in-the-nation position in the presidential nominating process.

But in the half-century arc of the state’s quirky caucuses, Obama’s victory proved to be an outlier. All other Democratic winners turned out to be also-rans.

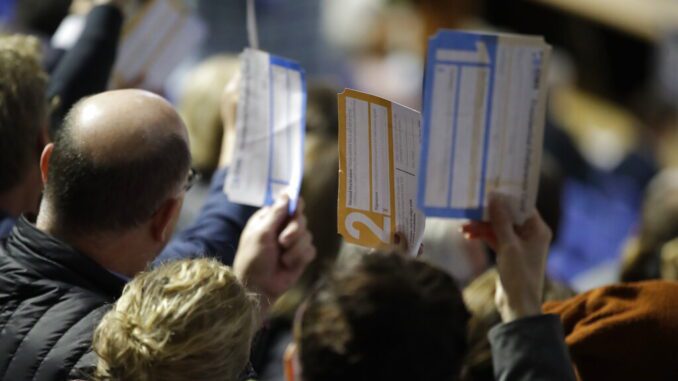

The caucuses and their outsize importance were largely an exercise in myth-making, that candidates could earn a path to the White House by meeting voters in person where they live, and earnest, civic-minded Midwesterners would brave the winter cold to stand sometimes for hours to discuss issues and literally stand for their candidate.

As the caucuses have played out, the flaws have become glaring. First among them: The state’s Democrats botched the count in 2020, leaving an embarrassing muddle. But there were more. Since 2008, the state’s political makeup has changed dramatically, from a reliable swing state to solidly Republican.

“We’ve been headed this way for a while,” said Joe Trippi, who managed Missouri Rep. Dick Gephardt’s winning Iowa campaign in 1988, adding “2020 broke the camel’s back.”

The Democratic National Committee’s rulemaking arm voted to remove Iowa as the leadoff state in the presidential nominating order and replace it with South Carolina starting in 2024, a dramatic shakeup championed by President Joe Biden.

The caucuses were once a novel effort to expand local participation in national party decision-making, but this vestige of 19th century Midwestern civic engagement has simply been unable to keep pace with the demands of 21st century national politics.

“The times have changed and maybe it’s time for this nominating process to change,” said Emily Parcell, Obama’s 2008 Iowa political director.

To much of the nation, the caucuses were a quadrennial curiosity, seen in TV shots framed by snowy cornfields, with a reminder piece the summer before featuring candidates awkwardly sampling the Iowa State Fair’s menu of fried food or gazing at a life-sized cow carved from butter.

The seeds of the myth were etched into the national narrative in the 1970s by a cadre of political writers, mostly from Washington, who tracked Indiana’s Birch Bayh, Arizona’s Mo Udall, Idaho’s Frank Church and an obscure governor from Georgia, Jimmy Carter, to cafes, VFW halls and living rooms.

Their stories offered a sheen of quaint civic responsibility, citizens meeting candidates, often several times, and a willingness to brave a bone-chilling winter night for them.

The caucuses are not elections, but rather party-run events, conducted by local Democratic officials and volunteers, a concept that has long bedeviled outsiders.

Like Iowa’s Republican Party caucuses, which remain first in the GOP’s 2024 presidential sequence, the Democratic caucuses are open only to voters who note the party affiliation on their voter registration.

Iowa first moved its caucuses from spring to winter before the 1972 campaign, and added a presidential vote to the agenda to invite more participation during an era of unrest.

“There was a kind of romanticism of neighbors gathering to make this important decision. There was something wholesome about that,” said Democratic strategist David Axelrod, who was senior adviser to Obama’s 2008 campaign.

“They took on sort of mythic importance and, over time, they became somewhat of an industry,” said Axelrod, who also advised the late Illinois Sen. Paul Simon’s 1988 campaign and former North Carolina Sen. John Edwards’ in 2004. “Some of that wholesomeness wore off.”

Likewise, the campaigns evolved from tests of more provincial interests to national trial runs.

Missouri Rep. Dick Gephardt won the 1988 Iowa caucuses on a local economic populist message aimed at addressing the financial crisis gripping Iowa farmers.

With each cycle, the Democrats’ criticism of Iowa as non-representative of the party increased, coming to a calamitous head on caucus night in February 2020.

A smartphone app designed to calculate and report results failed, prompting a telephone backlog that prevented the party from reporting final results for nearly a week after the Feb. 3 contest.

The Associated Press was unable to declare a winner after irregularities and inconsistencies marred the results. Top finishers Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg were denied the full measure of momentum ahead of New Hampshire eight days later.

“I think we all look back and recognize that was the death knell,” said John Norris, who managed Kerry’s 2004 Iowa campaign and the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s in 1988.