Note: Shawn Krest is embedded with a humanitarian aid group delivering food in the Ukraine. This is the third installment of his report on the experience. You can read the first two at

Keep on truckin’: First impression of Ukraine – The North State Journal (nsjonline.com)

On our way out in the morning, we suffer our first casualty. I’m riding in Nighthawk (the black van—there’s also Opal, a blue one and MomVan, a minivan) and it begins making a clunking noise about a mile into the trip.

“That’s new,” said the driver. The van then immediately lurches and we hear a loud clunk. As we pull to the side of the road, we see a trail of oil behind us. The white smoke and smell are not good signs.

I step out of the passenger side to assess the damage. From the driver’s seat, I get a reminder of where we are.

“Try not to step on the grass,” the driver said, pointing at the strip of lawn in front of a melon field.

Once we were loaded into MomVan and Opal and running again, a short distance down the road, I saw the “Danger: Land mines” sign. So, even the “relatively safe” area has its risks.

Once we were loaded into MomVan and Opal and running again, a short distance down the road, I saw the “Danger: Land mines” sign. So, even the “relatively safe” area has its risks.

***

Sometimes, the worst news comes in the form of a simple suggestion.

“You might want to bring extra water with you today,” team leader Shannon announced as we prepared to depart.

A reasonable piece of advice: For us newcomers, the task may end up being more strenuous than we expect, or perhaps the weather forecast calls for warmer than average temperatures.

“The Russians are trying to take out the bridge out of town,” he clarified. So we may be in the city … longer than we expect.

This piece of news, naturally, inspired several questions, all of which Shannon brushed off. “We’ll just bring extra water, and, if we need to, we’ll eat Christian first,” he said, gesturing toward the smallest driver in the group and least likely to put up a fight.

We are headed into the war zone today.

As we get closer to the front lines, military checkpoints are more numerous and better fortified. The soldiers manning them–scared young kids in the “relatively safe” area where we spent the first night, are now grizzled veterans.

We’re now down to two vans. We left Nighthawk by the potentially mine-filled farmer’s field and will arrange a tow from one of our contacts in the country. And we make our way into the heart of the city where bombings are a part of everyday life.

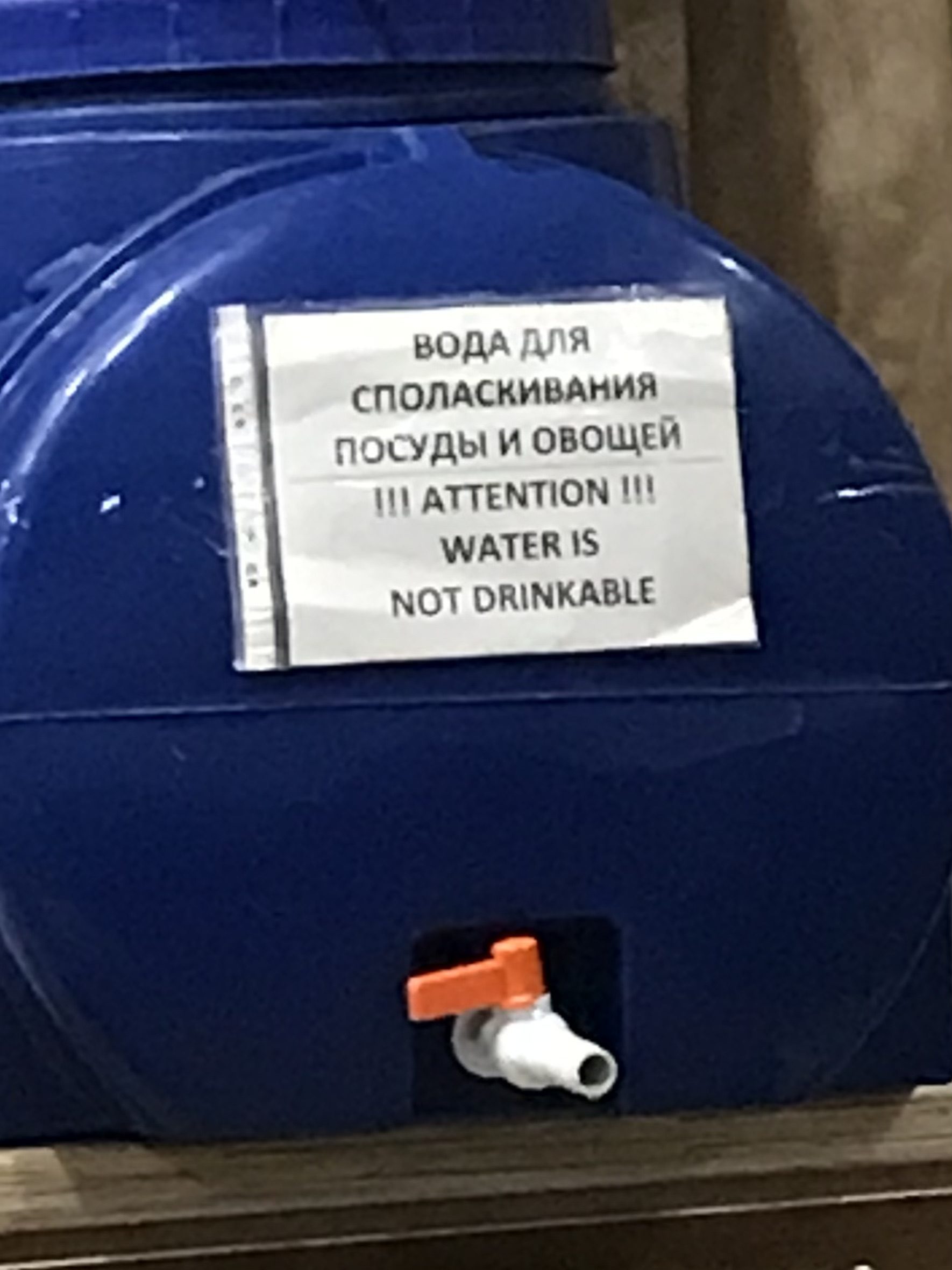

There is no fresh water here—the Russians cut a pipeline. We’ll be staying in a church attic and showering with sea water that they have rigged up to their plumbing.

There is no fresh water here—the Russians cut a pipeline. We’ll be staying in a church attic and showering with sea water that they have rigged up to their plumbing.

A bridge into town is down to one lane, the bottleneck a result of a bomb that left a crater in the slow lane. We pass a mall with boarded up windows.

“That got bombed because of TikTok,” Christian (as yet uneaten) explained. “Someone posted a video of soldiers in the mall, and the Russians were like, ‘We know where that is!’ and launched rockets.”

We stop at a university that was reduced to rubble by an attack last week. Work crews are busy clearing debris. Across the street is collateral damage—a line of small homes that were also heavily damaged in the attack.

None have any windows remaining. No roof is entirely undamaged. The elderly residents are still clearing rubble from their homes and approach us.

None of us speak Ukrainian, and they don’t understand English. We attempt to use a translation app to bridge the chasm, but it struggles, often returning nonsense phrases like “the cat has the car” and, we assume, likewise in Ukrainian.

Finally, we find a language that everyone can at least follow to some degree—Spanish. Igor, one of the residents, lived in Mexico for some time and Christian grew up in the Dominican. The rest of us have some familiarity due to high school, travel or interviewing minor league baseball players from the Caribbean.

We’ve brought tarps and weatherproof material for the roofs, but the residents don’t want it. They’ve already tarped and don’t want to replace their work with ours. I picture my own older relatives telling friends, “Some kids came to try to fix our roof,” then waving a hand dismissively. “Theyyyyy didn’t know what they were doing.”

So we settling on helping to board windows, using plywood and the weatherproof material. One family’s house also had the door literally blown off the hinges. Half of it remained, propped up to block the entryway. We split into a door team and window team and set to work.

The man who owns the home—and likely built the original door himself—insists on designing it, using pieces he can salvage from the damaged original. He refuses the translation app, miming instructions at us—hammer here, remove that.

My patience quickly wears thin. Working alone, I’d have responded with, “If you’re such an expert, have at it. I’ll go build a window.” But I follow the lead of the others and power saw where I’m told (and take the blame when he mismeasures, and a piece ends up too short). After all, this is his home, and the damage is not due to any fault of his. He just lived too close to a tactical target. It’s natural that he would want to take the lead on our repairs.

After a few hours, the work is done. The various neighbors claim the leftover wood and materials, knowing there’s a good chance they’ll need it again in the future.

Throughout the day, the air raid sirens sound again and again. We hear explosions—not far off rumbles that could be confused for thunder this time but actual impacts, somewhere across town, likely.

The church prepares about 200 bags of food—daily rations, they call them—which we deliver to distribution points in the city. We take six extra, to deliver to the families with newly boarded windows and a passing knowledge of Spanish.

We return to the church, where the cook has prepared a dinner of potato soup and some type of rice dish that seems like jambalaya without the spices. Still, it is far from bland—hearty and filling.

After clearing our plates, we remain at the table, talking. A half hour passes, and the cook comes to us, with another church employee.

“We pray now,” he says. “Hallelujah.”

After a few missteps, we determine that the employees hold a nightly prayer session, which is scheduled to begin now. So we need to move our discussion to the attic.

I collect my things but then hesitate. We are staying in their church. They are feeding us, with food that otherwise would be earmarked for their countrymen. They are gathering in their kitchen, which has the stairway to the basement bomb shelter in one corner, to pray, likely before the Russians begin bombing their city again tonight.

I remain in my seat and stand when the two men enter and stand together on one side of the kitchen.

A group of women employees enter and sit. A third man stands in the doorway.

The two men begin to pace back and forth across the kitchen, mumbling “hallelujah” to themselves, over and over.

There’s a fine line between respect and mockery, so I remain standing, flat footed, rather than follow them. One of the men begins making chirping noises in between the hallelujahs.

The cook stops pacing and speaks urgently for about five minutes, eyes closed and hands waving. Several phrases start with a word that sounds like “basta” which he later explains means something similar to “pray” or “rejoice”.

The two men take turns speaking prayers, then each returns to pacing, chirping and mumbling hallelujah. When they pray, I use my translation app to follow along.

One of the men then turns to me and asks me to read the English translation out loud. He gestures toward the other American drivers, who have returned to the kitchen to see what they were missing.

“Our position is at the foot, and the nails, Lord,” I read. “Where there is a foundation for our hearts. We stand and obey your will, because the keys to death are in your hand.”

It’s a grim prayer, for a grim time. One of the women then prays, asking the lord to watch over the Americans who have driven so far to help them.

With that, the vigil ends and it is lights out in the church, as well as everywhere across the city. A nightly full darkness curfew is in effect. We return to the attic and set up our sleeping bags, air mattresses and cots in the dark and settle in to wait for morning or sirens to wake us.