NEW YORK — David McCullough, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author whose lovingly crafted narratives on subjects ranging from the Brooklyn Bridge to Presidents John Adams and Harry Truman made him among the most popular and influential historians of his time, has died. He was 89.

McCullough died Sunday in Hingham, Massachusetts, according to his publisher, Simon & Schuster. He had been in failing health and died less than two months after his beloved wife, Rosalee.

“I think because of David a lot of us feel a twin obligation,” fellow historian Jon Meacham said Monday. “One is to the historical record and to the analysis. And the other is to the reader who would like to be transported, both intellectually and viscerally.”

A joyous and tireless student of the past, McCullough dedicated himself to sharing his own passion for history with the general public. He saw himself as an everyman blessed with lifelong curiosity and the chance to take on the subjects he cared most about. His fascination with architecture and construction inspired his early works on the Panama Canal and the Brooklyn Bridge, while his admiration for leaders whom he believed were good men drew him to Adams and Truman. In his 70s and 80s, he indulged his affection for Paris with the 2011 release “The Greater Journey” and for aviation with a best-seller on the Wright Brothers that came out in 2015.

Beyond his books, the handsome, white-haired McCullough may have had the most recognizable presence of any historian, his fatherly baritone known to fans of PBS’s “The American Experience” and Ken Burns’ epic “Civil War” documentary. “Hamilton” author Ron Chernow once called McCullough “both the name and the voice of American history,” while on Monday Burns tweeted that McCullough was a friend and “gifted teacher” to him.

He helped raise the reputations of Truman and Adams, and he started a wave of best-sellers about the American Revolution, including McCullough’s own “1776.” Well into his 80s, his books remained popular and seemed to inspire renewed interest in the subject.

McCullough received the National Book Award for “The Path Between the Seas,” about the building of the Panama Canal; and for “Mornings on Horseback,” a biography of Theodore Roosevelt; and Pulitzers for “Truman,” in 1992, and for “John Adams” in 2002. “The Great Bridge,” a lengthy exploration of the Brooklyn Bridge’s construction, was ranked No. 48 on the Modern Library’s list of the best 100 nonfiction works of the 20th century and is still widely regarded as the definitive text of the great 19th century project. Upon his 80th birthday, his native Pittsburgh renamed the 16th Street Bridge the “David McCullough Bridge.”

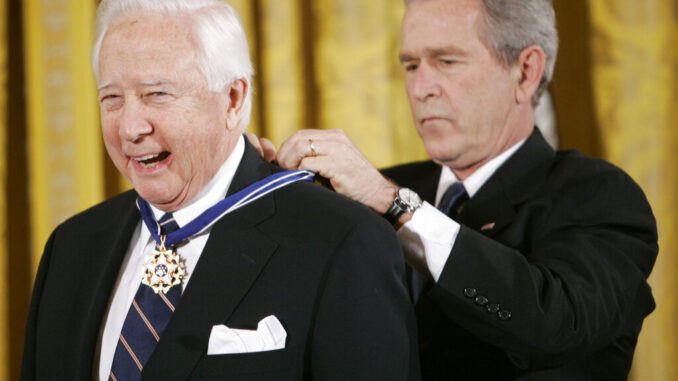

McCullough also was a favorite in Washington, D.C. He addressed a joint session of Congress in 1989 and, in 2006, received a Presidential Medal of Freedom. Politicians frequently claimed to have read his books, especially his biographies of Truman and Adams. Jimmy Carter cited “The Path Between the Seas” as a factor in pushing for the 1977 treaties which returned control of the Panama Canal to Panama, and politicians on both sides of the issue cited it during debate. Barack Obama included McCullough among a gathering of scholars who met at the White House soon after he was elected.

McCullough also had one emphatic cause: education. He worried that Americans knew too little about history and didn’t appreciate the sacrifices of the Revolutionary era. He spoke often at campuses and before Congress, once telling a Senate Committee that because of the No Child Left Behind act “history is being put on the back burner or taken off the stove altogether in many or most schools, in favor of math and reading.”

Impassioned about the past, McCullough was active in the preservation of historical regions. He opposed the building of a residential tower near the Brooklyn Bridge and was among the historians and authors in the 1990s who criticized the Walt Disney Company’s planned Civil War theme park in a region of northern Virginia of particular historical significance.

“We have so little left that’s authentic and real,” McCullough said at the time. “To replace what we have with plastic, contrived history, mechanical history is almost sacrilege.”

McCullough, whose father and grandfather founded the McCullough Electric Company, was born in Pittsburgh in 1933. He loved history as a child, recalling lively dinner conversations, portraits of Washington and Lincoln that seemed to hang in every home and the field trip to a nearby site where Washington fought one of his earliest battles. He majored in English at Yale University and met playwright Thornton Wilder, who encouraged the young student to write.

McCullough had five children and an affinity for happily married politicians such as Truman and Adams that could be traced to his wife, Rosalee Barnes, whom he married in 1954 and who died in June. She was his editor, muse and closest friend. At his home in Martha’s Vineyard, McCullough would proudly show visiting reporters a photograph of their first meeting, at a spring dance, the two gazing upon each other.