RALEIGH — The outsized attention placed on the 11th Congressional District Republican primary was driven by the tumultuous 18 months Madison Cawthorn spent as a first-term Congressman. Yet without the entry of Chuck Edwards into the field, he would be on the path to reelection.

The race truly began when the General Assembly’s 2021 redistricting session got underway last fall. Following statewide public hearings and draft proposals that garnered much attention on Twitter, the legislature placed a new district between the mountains and Mecklenburg County – and political observers seemed certain that House Speaker Tim Moore (R-Kings Mountain) would run for the seat.

That, of course, didn’t happen, with Cawthorn saying he would leave his western NC district and run in the new one. In his words, it was to keep an “establishment, go along to get along Republican” from winning.

“This was a tactical move to ensure North Carolina’s conservative fighting spirit is strengthened,” Cawthorn said in a video announcing the move.

A host of candidates would announce their campaigns without the presence of an incumbent, Edwards among them. However, state courts got involved, and in a series of courtroom moves the legislative map was discarded. In that time, though, Cawthorn’s move drew ire from the people who sent him to Washington in the first place. None of the candidates who got into the race left – including Edwards.

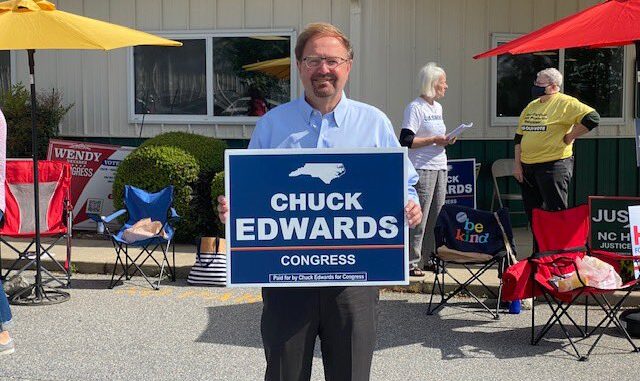

First elected to the state Senate in 2016, Edwards succeeded one of the most powerful legislators in Raleigh, Tom Apodaca. Edwards’ business background – he started working at a local McDonald’s at the age of 16, eventually rising through the corporate structure, and owning multiple franchises – is a compelling story.

“I was born and raised here in the very mountains that I’m now asking to represent. As a child, I was a member of a very religious but poor family. My mom was a waitress; my dad was a truck driver. We didn’t have much, but we had love and togetherness,” Edwards told North State Journal in a December 2020 interview.

With district lines finalized in February, the sprint was on to the May 17 primary for Cawthorn, Edwards, and six other candidates.

Cawthorn was the focus of many liberal activists in Asheville and nationwide. Led by his 2020 opponent, Democrat Moe Davis, a PAC called “Fire Madison Cawthorn” recruited a moderate registered Republican into the race and spent thousands viciously attacking the first-term Congressman. Democrats in the race regularly invoked Cawthorn making appeals to small-dollar donors that would go viral.

Cawthorn’s biggest problem, though, was a serious candidate who happened to be a third-term state legislator representing the same areas that powered his improbable rise in 2020.

The majority of votes in the primary would come from a group of three counties: Buncombe, Henderson, and Transylvania. Buncombe, the most populous of the three, is home to the liberal bastion of Asheville but also nearly 46,000 Republicans. The GOP outnumbers registered Democrats in Henderson and Transylvania.

Both Cawthorn and Edwards call Henderson County home.

In 2020, Cawthorn advanced to a runoff with Lynda Bennett based off of winning Buncombe and Henderson counties in the first primary. In the runoff, Cawthorn swept to victory with 66% of the vote.

As the race entered Spring, it looked as though it was Cawthorn vs. the field. Some of the other candidates would have a fleeting rise: Bruce O’Connell spent personal money freely in TV ads, Michele Woodhouse, a one-time Cawthorn ally and former 11th District Republican chairwoman, made the rounds in conservative media, and some in the Buncombe County business community backed Matthew Burrill, a 35-year financial advisor and Chairman of the Asheville Regional Airport Authority.

The race even gave reason for Bob Orr, a former Republican who has spent the better part of the past decade slamming his former party, to launch a podcast about the race.

As controversies rained down on Cawthorn, most through his own making, the only other candidate in the race who had served in elected office was Edwards. Carrying endorsements from many of western NC’s state legislators, Edwards was now looked at as the alternative candidate.

An April memo published by campaign consultant Paul Shumaker laid out their path to victory.

“Past election trend data shows a vote goal of 17,250 votes will put Edwards over the top of all other candidates. Our mail is focused on Chuck’s record of accomplishments and the issues our polling shows will defeat Madison Cawthorn: his poor voting record coupled with excessive spending, cutting social security and veterans benefits and requiring seniors to go back to work to receive social security benefits, and instituting a new European-style consumption tax,” part of the memo read.

It also said that if no one rises to the task of focusing on the issues that matter against Cawthorn, we will have no choice but to go directly after him.

In a timely turn of events, the controversies that made national news spurred the involvement of state Republicans whose private antipathy towards Cawthorn led to public action. U.S. Sen. Thom Tillis and legislative Republicans rallied to Edwards, helping fundraise across the state and generating enough outside interest to pepper voters with TV ads, mail, digital ads, and more.

From March to April, Cawthorn dropped 11 points and Edwards rose by 7, according to polling conducted in the race by the GOPAC Election Fund.

“Typically, undecided voters break toward challengers and nonviable candidates lose voters to true contenders as an election nears. Among voters who have an opinion of both Edwards and Cawthorn, Edwards led 32% to 31%. If Cawthorn is going to lose, it will be Edwards who beats him,” said political consultant Jim Blaine, who led the organization’s polling efforts.

At the start of early voting, it was clear there was strong interest in the race. Republicans turned out, and critically, so did unaffiliated voters. Shumaker’s original estimate was well below where the race would end up.

In the three weeks before May 17, Edwards would raise $121,700 according to FEC records. In comparison, Cawthorn raised just $15,500. As the viable alternative, Edwards had all the momentum going into Election Day.

Edwards built a nearly 4,000 vote lead in combined absentee and one-stop voting. That strength came mainly in Buncombe, Henderson, and Transylvania counties.

When Election Day votes were tallied, Cawthorn led by just 2,500. Not even a last-minute plea from former President Donald Trump on TRUTH Social, in which he urged voters to give Cawthorn a second chance, seemed to break through.

As precincts reported their numbers, it was becoming evident Edwards would narrowly win.

In Buncombe County, Edwards outpaced Cawthorn by 11%. In Henderson and Transylvania, it was nearly identical: Edwards took 43% and 50%, respectively, with Cawthorn at 25% in each county.

That was enough to offset Cawthorn’s wins in the remaining 12 counties. His best result came in Cherokee County, the state’s westernmost, where he led Edwards 46% to 21%.

Acknowledging his defeat, Cawthorn conceded the race to Edwards and urged Republicans to come together to win in November.

Edwards said “I am forever grateful for the trust you’ve placed in me to be the GOP nominee. Let’s take the gavel from (House) Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s hands in November!” in a statement on Twitter after the win. He also thanked every candidate for their graciousness, including Cawthorn.

In the final tallies, Edwards took 29,411 votes to Cawthorn’s 28,092. The next highest finisher, Burrill, recorded 8,314 votes.

Edwards is now a heavy favorite to beat the Democratic nominee, Jasmine Beach-Ferrera, in a district and political environment that favors Republicans.