The congressional redistricting wars are mostly over. Much of the hoopla surrounding it is proving overheated.

Before looking at this cycle’s results, a primer on the subject is in order.

The first and most important point is that the requirement that districts have equal populations seriously limits the effects of partisan redistricting. That requirement seems to have been on the minds of the framers of the Constitution.

The framers mandated a federal census to be conducted every 10 years to determine the apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives based on population. Ours was, I believe, the first regularly scheduled national census in history, and it was among the first to link representation to population.

The argument that the framers favored districts with equal populations is strengthened by the fact that the number of seats they allocated the states in 1787 for the first Congress tracks pretty closely the numbers resulting from the results of the first census in 1790.

In 1842, Congress specifically required the states to create districts with equal populations. That provision was dropped in 1929, when Congress adopted an automatic formula for reapportionment after each census. But in 1964, the Supreme Court imposed a “one-person, one-vote” standard on both congressional and state legislative districts — a result that I think the framers would have found congenial.

But the equal populations leave some limited room for political manipulation. To see why, imagine a square-shaped state entitled to two districts, whose northern half votes 55% Republican and whose southern half votes 65% Democratic. If you divide the districts by a north-south line, you’ve got two 55% Democratic districts. An east-west line gives you one Republican and one Democratic district. Which plan is fairer? It sort of depends on which party you favor, doesn’t it?

What happens if opinion shifts 10 points away from the Democrats, as has happened frequently and may have happened since November 2020? Then the north-south line produces two Republican districts, but the east-west line still produces one district for each side.

Which plan is fairer? You can make arguments either way.

The situation in states with multiple districts is not so simple, except maybe in New Hampshire, which has not changed the boundaries of its two districts much since 1881 but may this time, but the principle is the same. One corollary is that there is no truly nonpartisan way to draw district lines. A redistricter with no knowledge of partisan patterns — and no one interested enough in the issue lacks all such knowledge — will draw lines that will favor one party more than the other and one party’s factions more than their rivals.

But as our second hypothetical shows, the boundaries may not favor the intended party when opinion changes. Districts full of college graduates who favored Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) in 2012 were voting Democratic in 2018 and 2020. Districts full of noncollege white voters who favored President Barack Obama in 2012 were voting Republican in 2016 and 2020.

Redistricters who drew the boundaries in 2011 and 2012 didn’t and couldn’t foresee those changes. Redistricters drawing boundaries in 2021 and 2022 do not and cannot know how different groups’ political views will change by 2030 — and maybe even by 2024.

The concentration of a party’s votes also makes a difference, putting it at a disadvantage in equal-population districting, for reasons suggested by our square state hypothetical. In recent elections, Democratic voters have been heavily concentrated in central cities, sympathetic suburbs and university towns, while Republican voters are spread more evenly around the rest of the country.

This enabled Donald Trump to win one presidential election and nearly win a second despite trailing Democrats in popular votes. But Republicans haven’t always had the advantage here. George W. Bush and Obama both won 51% of the popular vote when they were reelected. But Obama’s 51% gave him 332 electoral votes, while Bush’s gave him only 286.

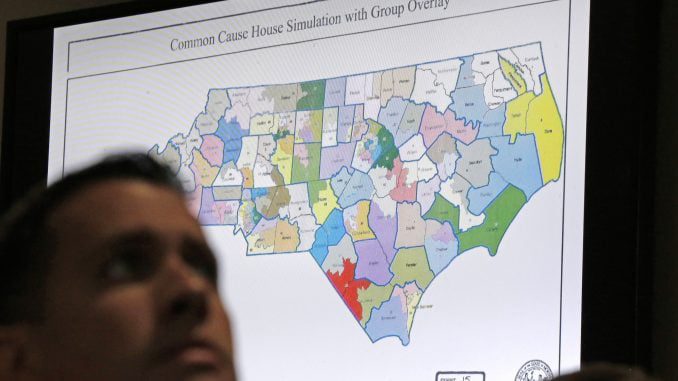

Democrats’ demographic concentration means that Democratic redistricters have to draw more grotesquely shaped districts than Republicans. Cook Political Report’s ace redistricting expert David Wasserman noted that Florida, Ohio and New York all have anti-gerrymandering provisions in their state constitutions, but only in Democratic New York was a redistricting plan thrown out for 2022 on those grounds.

But then, take a look at the maps. The New York Democrats’ plan had multiple districts as uncompact as Elbridge Gerry’s 1812 masterpiece, from which the term “gerrymandering” comes. The Florida and Ohio Republicans’ districts, on the other hand, have relatively compact shapes and clean lines.

Wasserman correctly noted that the New York court’s decision tilts the total effect of redistricting toward Republicans. But the Democrats’ advantage that he was among the first to spot, and that I failed to foresee, was produced by partisan state courts in Pennsylvania and North Carolina. Also, a supposedly nonpartisan commission in California produced a partisan gerrymander as grotesque as anything produced by the late Rep. Phillip Burton (D-California). Liberals who have been screaming that partisan redistricting means the end of democracy didn’t have much to say about these plans, apart from gloating.

Since the Supreme Court’s 1964 decision, neither party’s redistricting advantages have proved permanent. Liberals seldom complained about the Democrats’ significant redistricting advantages in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. They only spied a threat to democracy when Republicans developed similar advantages in the 2000s and 2010s. The 1990s were a wash in partisan terms, and the 2020s look to be close to a wash as well.

Neither party has had a large enough redistricting advantage to retain majorities in the House for a full inter-census decade since the 1980s, the heyday of Burton, who was succeeded in 1983 by his widow and in 1987 by Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-California). Despite Republican redistricting plans, she is now serving her eighth year out of the last 16 as speaker of the House. Partisan redistricting is not a threat to democracy; it’s just a marginal and unavoidable factor in a system that links representation to population.

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and longtime co-author of The Almanac of American Politics.