The central question we face today is: Who decides?

No one doubts that the COVID–19 pandemic has posed challenges for every American. Or that our state, local, and national governments all have roles to play in combating the disease. The only question is whether an administrative agency in Washington, one charged with overseeing workplace safety, may mandate the vaccination or regular testing of 84 million people. Or whether, as 27 States before us submit, that work belongs to state and local governments across the country and the people’s elected representatives in Congress.

This Court is not a public health authority. But it is charged with resolving disputes about which authorities possess the power to make the laws that govern us under the Constitution and the laws of the land.

I start with this Court’s precedents. There is no question that state and local authorities possess considerable power to regulate public health. They enjoy the “general power of governing,” including all sovereign powers envisioned by the Constitution and not specifically vested in the federal government. And in fact, States have pursued a variety of measures in response to the current pandemic.

The federal government’s powers, however, are not general but limited and divided. See McCulloch v. Maryland, (1819). Not only must the federal government properly invoke a constitutionally enumerated source of authority to regulate in this area or any other. It must also act consistently with the Constitution’s separation of powers. And when it comes to that obligation, this Court has established at least one firm rule: “We expect Congress to speak clearly” if it wishes to assign to an executive agency decisions “of vast economic and political significance.” We sometimes call this the major questions doctrine.

OSHA’s mandate fails that doctrine’s test. The agency claims the power to force 84 million Americans to receive a vaccine or undergo regular testing. By any measure, that is a claim of power to resolve a question of vast national significance. Yet Congress has nowhere clearly assigned so much power to OSHA. Approximately two years have passed since this pandemic began; vaccines have been available for more than a year. Over that span, Congress has adopted several major pieces of legislation aimed at combating COVID-19. But Congress has chosen not to afford OSHA — or any federal agency — the authority to issue a vaccine mandate. Indeed, a majority of the Senate even voted to disapprove OSHA’s regulation. It seems, too, that the agency pursued its regulatory initiative only as a legislative “work-around.” Far less consequential agency rules have run afoul of the major questions doctrine. It is hard to see how this one does not.

What is OSHA’s reply? It directs us to 29 U. S. C. § 655(c)(1). In that subsection, Congress authorized OSHA to issue “emergency” regulations upon determining that “employees are exposed to grave danger from exposure to substances or agents determined to be toxic or physically harmful” and “that such emergency standard[s] [are] necessary to protect employees from such danger[s].” According to the agency, this provision supplies it with “almost unlimited discretion” to mandate new nationwide rules in response to the pandemic so long as those rules are “reasonably related” to workplace safety.

The Court rightly applies the major questions doctrine and concludes that this lone statutory subsection does not clearly authorize OSHA’s mandate. As the agency itself explained to a federal court less than two years ago, the statute does “not authorize OSHA to issue sweeping health standards” that affect workers’ lives outside the workplace.

Yet that is precisely what the agency seeks to do now — regulate not just what happens inside the workplace but induce individuals to undertake a medical procedure that affects their lives outside the workplace. Historically, such matters have been regulated at the state level by authorities who enjoy broader and more general governmental powers. Meanwhile, at the federal level, OSHA arguably is not even the agency most associated with public health regulation. And in the rare instances when Congress has sought to mandate vaccinations, it has done so expressly. We have nothing like that here.

The question before us is not how to respond to the pandemic, but who holds the power to do so. The answer is clear: Under the law as it stands today, that power rests with the States and Congress, not OSHA.

In saying this much, we do not impugn the intentions behind the agency’s mandate. Instead, we only discharge our duty to enforce the law’s demands when it comes to the question who may govern the lives of 84 million Americans. Respecting those demands may be trying in times of stress. But if this Court were to abide them only in more tranquil conditions, declarations of emergencies would never end and the liberties our Constitution’s separation of powers seeks to preserve would amount to little.

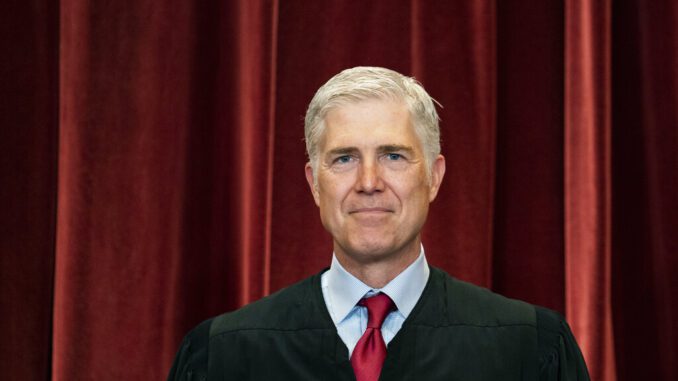

This is an abridged version of Justice Gorsuch’s concurring opinion in the NFIB v OSHA case decided on Jan. 13, 2022. The full court opinion can be read here.