Thick as a Manhattan phone book and as confusing as a set of IKEA assembly instructions, the NCAA rules manual is a publication filled with contradictions.

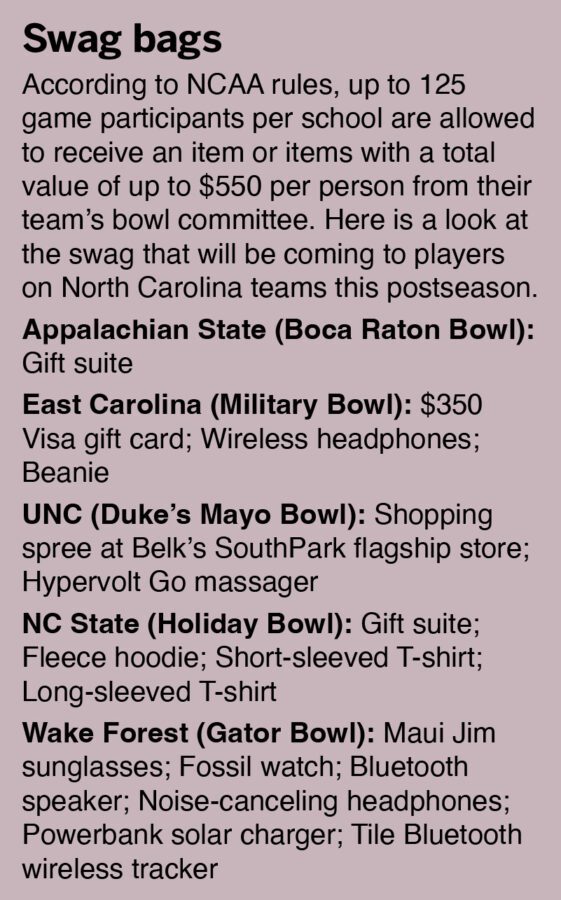

Among the most confounding are regulations that could render an athlete ineligible for accepting a free lunch yet allow postseason football bowls to lavish that same player with up to $550 in gifts just for being selected to play in their games.

At least some of the hypocrisy was eliminated last summer when the NCAA Council adopted legislation that allows college athletes to monetize their name, image and likeness. It’s a change bowl committees have quickly embraced by finding creative new ways to compensate their participants while also promoting both their events, as well as those of their corporate sponsors.

“NIL has created unique promotional opportunities for bowl games to work alongside college athletes,” said Blake Lawrence, CEO of Opendorse, a third-party company that works to enhance the endorsement value of those athletes. “The players are the most relevant, influential ambassadors available to these games.”

Each of the 43 Division I postseason games sanctioned by the NCAA this year continue to reward their participants with a variety of swag, ranging from shirts and hats with the bowl’s logo on them to gift suites stocked with popular electronics.

Some, however, have gone even further thanks to the latitude afforded them by NIL.

Charlotte’s Duke’s Mayo Bowl, for instance, has announced a program that will compensate selected members of the two participating teams — North Carolina and South Carolina — to tell the story of their experience leading up to the game at Bank of America Stadium on Dec. 30.

In addition to documenting sponsored team activities such as the traditional ride-along at Charlotte Motor Speedway and a shopping spree at Belk’s flagship store in SouthPark Mall, the players will also use their social media accounts to promote the title sponsor and the bowl.

In addition to documenting sponsored team activities such as the traditional ride-along at Charlotte Motor Speedway and a shopping spree at Belk’s flagship store in SouthPark Mall, the players will also use their social media accounts to promote the title sponsor and the bowl.

Afterward, a member of the winning team — not necessarily the game MVP — will be offered a $5,000 contract as a “Duke’s Mayo Bowl Ambassador” to continue telling the story of the event into the offseason.

“We think it’s going to be an excellent opportunity and platform to have players engaged in telling the stories about their experiences at the bowl,” said Danny Morrison, executive director of the Charlotte Sports Foundation, the organization that runs the state’s only bowl game.

“We think this can be an inside look from a players’ standpoint, so we’re excited about the possibilities. It’s a way to talk about the bowl and about Duke’s Mayo, and hopefully we’ll have fun with it as well.”

Thanks to the efforts of marketing director Miller Yoho, the Charlotte bowl has raised its profile nationally since partnering with Duke’s last year. Among its most popular gimmicks is an offer to donate $10,000 to charity if the winning coach allows himself to get doused with mayonnaise at the end of the game rather than the usual Gatorade shower.

“Our philosophy is that we take what we do every day seriously, but we don’t take ourselves too seriously,” Morrison said. “We want the game to be a bowl that has energy and shows people that it’s a fun brand and a great brand.”

Not everyone has been as quick or as decisive in implementing NIL programs.

Steve Beck, executive director of the Military Bowl in Annapolis, Maryland, said he and his staff are still in the brainstorming stage and trying to determine how best to use their new freedom to market their game, sell tickets and, most importantly, call attention to Patriot Point.

Proceeds from the bowl, which will be played on Dec. 27 between East Carolina and Boston College, go to benefit the 290-acre retreat for recovering service members, their families and caregivers on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

“I’m hoping my people get really creative as they figure out how to approach this,” Beck said. “It’s interesting and exciting to see how it might impact this next generation of fans and the connectivity they have with the players. You just have to look at each team and try to determine who has a good following and try to create a promotion that goes along with that. That’s what we’re trying to determine now.”

One idea that is strictly off the table is crossing the line into play-for-pay by offering draft-eligible stars appearance fees to prevent them from opting out. Even if it was legal, Bowl Season executive director Nick Carparelli said it wouldn’t be financially feasible for a game or its sponsor to pay the kind of money it would take to change a potential first round draft pick’s mind about playing.

Still, speculation on the subject was raised recently when UNC quarterback Sam Howell announced his decision to play in the Duke’s Mayo Bowl with a social media post featuring a gif of Homer Simpson guzzling a jar of mayonnaise.

Howell debunked that conspiracy theory by saying he “thought it would be something funny” to show his excitement about playing another game with his teammates.

“Anybody who tries to make the case that he’s playing because there’s some NIL incentives out there for his entire team is mistaken,” said Carparelli, whose organization binds all 42 postseason games into a single entity.

Because each state has different laws concerning NIL and the NCAA hasn’t yet instituted its own blanket guidelines, Carparelli said that there’s no single format for how it should be used. As such, the session on NIL at Bowl Season’s annual meeting last summer — which included a representative of Opendorse as well as other experts on the subject — drew by far the most interest among its members.

But as Gator Bowl executive director Greg McGarity notes, NIL arrangements aren’t for everyone.

“Every situation is unique,” said McGarity, whose New Year’s Eve game in Jacksonville, Florida, matches Wake Forest and Texas A&M. “It’s another tool in the tool chest, but we felt that with the teams we have this year, it’s not a wise investment for us considering the dynamics that are in play.”

NC State (Holiday Bowl vs. UCLA) and Appalachian State (Boca Raton Bowl vs. Western Kentucky) are the other state teams participating in the postseason this year.

“NIL is such a new thing for all of us in college athletics. I think we’re learning as we go,” Carparelli said. “The bowl organizations are no different than the college and universities and the student-athletes themselves in terms of figuring out what they can and can’t do, how to use it to their advantage and how the entire system works.

“We still don’t have all the answers, but it got everybody thinking. This year for us, just like everybody else, there’s going to be a steep learning curve. As we get into subsequent years, we will have a lot more to go on.”