RALEIGH — John Hood, president of the John William Pope Foundation, who has spent his career writing about history and economics and leading conservative North Carolina non-profits, decided recently to try something completely different: writing a historical fantasy series. Hood spoke with NSJ on Dec. 17 to explain his motivation for going in this new direction, his process for writing a novel and how his work is being received now that it’s published.

“I had never really anticipated writing a novel,” Hood said. “I wrote nonfiction books, and I wrote a lot of them, and I wrote lots of journalism. I wasn’t convinced that I could translate my writing capacity over to fiction. Of course, my critics have always said that I wrote fiction. But I mean intentionally writing fiction seemed a bit of a stretch.”

Another potential hurdle was that after writing so many nonfiction books, John’s wife had told him, after a 2015 biography of former Gov. Jim Martin, “No more books.” He said she wanted him to spend less of his home hours buried in historical research and more with family. Hood mostly agreed to these terms, but he also felt the pull of an image in his mind, the image that would give birth to “Mountain Folk” and the subsequent books in the series.

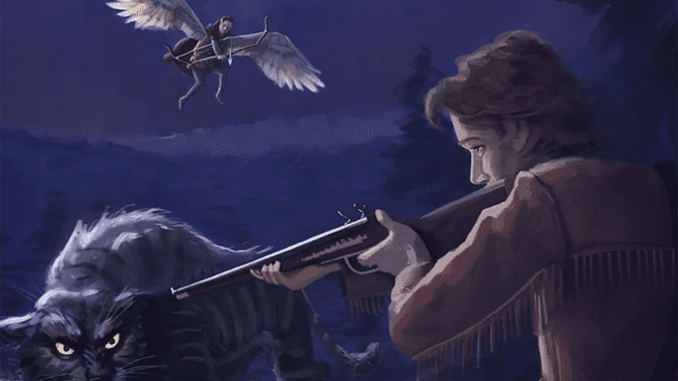

“So I had this idea, this image, that had been nagging me for years — this image of a young Daniel Boone coming down to North Carolina from Pennsylvania with his family… And I just had this image of him going hunting one night and encountering magical creatures.”

Other authors, like JRR Tolkein, who wrote the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy and “The Hobbit,” also report that their creative process started with a single image. For Tolkein, he said he was grading papers at Oxford University and wrote on a student’s paper, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” He then spent years creating “Middle Earth” around that hobbit and his hole.

“It wasn’t ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit,’ but it was very similar,” Hood said when asked about the connection. “I had a young Daniel Boone, teenage Daniel Boone, buckskin shirt, old hunting rifle. It’s dark. He’s traipsing up a mountain. There’s a winged fairy. A giant monster cat attacks. That’s basically what I had. I didn’t know what else I had. But that’s what I had.”

Hood did his best to ignore this image and keep to his promise to write no books, but then he got very sick around the Christmas of 2019.

“I’m not a very good sick person. I’m not a very good patient,” Hood said. “So I said, you know, I’m kind of bored. I’ll write a little story like this and hand it off to my wife and my brother, and they’ll get a kick out of it. So that’s what I did. It took the better part of an afternoon maybe, and I handed it off to Mrs. Hood and to my brother, who lives in Hickory, and went back to bed.”

Hood said about an hour later, his wife came into the room where he was sleeping and looked at him for a minute and then just said, “Where’s Chapter Two?”

“So the judge had modified her order,” Hood said on how he understood the implication of his wife’s question. “I was not allowed to write any more nonfiction books. But, apparently, I was not enjoined from writing fiction books. So I proceeded to write a heavily researched historical fantasy novel. Probably more research than I’ve done for any book.”

And while Hood initially worried that his journalism and more-academic writing style wouldn’t translate into novel writing, especially when creating dialogue, he found that it wasn’t as foreign as he anticipated. Part of it, he said, was getting into the “right frame of mind,” returning to some of the lessons he had learned in theater and performance.

“What I needed to do was create a situation in my imagination and then sort of let the characters say their lines in my head and then write them down, instead of trying to actively write dialogue,” he said.

He said the key for him was creating well-developed characters and a basic plot, and then just allowing the characters to decide what happens from there, even if you had planned on them doing something completely different.

“In fact, about half-way through, I was trying to get my characters to do things that were in my plot outline and they refused, of course metaphorically speaking,” Hood recalled. “So, you will find this also kind of flighty and silly, but towards the end, there is a climactic episode that corresponds to the Battle of Yorktown. And as I was writing that next to last chapter, I genuinely wasn’t sure the fate of certain characters, and I was kind of on the edge of my seat.”

But Hood said he only allowed the characters to rule so much, since he wanted the historical conclusions of the battles and events to be accurate, even if the mythical creatures added extra context that isn’t in the official record. The point of making the setting of the fantasy story in real history, and then staying true to the bigger picture of that history, is, for Hood, a way to teach important lessons and events in a digestible format for the average person.

“Having spent most my life in public-policy work and journalism, I want to think that a carefully researched white paper or a really, really fabulous speech, or a persuasive op-ed is going to change how people think about a political issue, and my somewhat reluctant conclusion is that those expectations are unrealistic,” Hood said. “I’m in favor of doing all of those kinds of activities, and I continue to do those kinds of activities, but they’re not sufficient. Most people have learned what they know about politics and government in ways other than policy analysis or serious journalism. They learned it by reading books, watching movies, telling stories.”

Hood said that it’s likely more people have learned about totalitarianism from reading George Orwel than they have from reading “some lengthy history of the Soviet Union or Hitler’s Germany” or the Federalist Papers. There are also major life lessons learned from non-historical stories like the “Lord of the Rings,” which can teach you about the temptations of power, among many other things, even if the events never occurred.

“Narrative is so important,” Hood said. “We are creatures who tell stories around the campfire, and that long predates any writing system or social science or anything like that. We taught each other important things about life, death, freedom and danger by telling stories around the campfire. So, I’m convinced that if I want to do my part to defend America’s traditions of freedom and order and constitutional government, then I need to be willing to tell stories, including imaginative stories, in order to reach people where they are.”

In terms of the narrative of the book itself, as Hood sums it up, “It’s got lots of thrilling escapes, confrontations with magical monsters, battles of the Revolutionary War, and Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson debate banking regulations. I mean, what more could you ask for?”

There are also “fairies,” which Hood means in the broader sense of all “wee folk” — dwarves, pixies, elves, etc — who live in hidden places among us, where time is slower, as opposed to humanity’’s faster pacing of time, which they call “the Blur.” These fairies interact with the key historical figures like Boone and Washington and have to decide how to respond to or even participate in the Revolutionary War. The Cherokee Nation, also observing the war brewing, plays a large part in the story and has to weigh the same questions as well.

Hood said he has heard from history teachers that “Mountain Folk” has been a way to make the stories come alive a little bit more, especially for those who have seen the subject as mostly memorizing dates.

“I’ve also heard from parents — homeschooling parents or parents who just don’t think their children get enough into history,” Hood said. “They’ve either handed the book off to a kid or they’ve been reading it [together]. One mother has been reading from the book every night, which is great.”

The second book, “Forest Folk,” comes out in April, and Hood also has plans for two more, “Water Folk” and “Valley Folk,” the last of which takes place during the Civil War.