Santa Fe, N.M. — Internet problems continue to slow down many students in the U.S. state of New Mexico, but a pilot project using TV signals to transmit computer files may help.

Last Thursday, state public-education officials distributed devices to eight families in the city of Taos that allow schools to send them digital files via television. The boxes the size of a deck of cards allow digital television receivers to connect with computers using technology called datacasting.

Many rural areas of New Mexico are too far from internet infrastructure like fiber cables and cell towers but do get TV reception.

In October, local broadcasting affiliates of New Mexico PBS finished testing the technology to make sure they could set aside bandwidth not taken up by TV show broadcasts and dedicate it to broadcast downloadable digital files.

The pilot program in Taos relies on a broadcast from northern New Mexico PBS affiliate KNME, while two others are planning to roll out pilot programs in the cities of Silver City and Portales.

Remote learning during the pandemic highlighted the digital divide for New Mexico students, many of whom had to learn using paper packets while their peers could participate in virtual lessons via video chat.

Even with schools back to offering in-person classes, internet inequality persists after class when students do homework, and for students being quarantined due to virus concerns.

Even where families are in internet coverage areas, it’s not always enough for the entire household.

“It’s very slow and I have a lot of students,” said Ofelia Muñoz, a mother of four in Ranchos de Taos who has a monthly subscription to a cable internet service. “It’s bad when they have to do homework.”

One of her children is a university student, who takes most of his classes online, and won’t be connected through the TV broadcast. But if his younger siblings can access a virtual library of school materials through the new device, it will lower the overall burden on their bandwidth.

“It’s easier when they can work at the same time,” she said.

New Mexico isn’t the first state to experiment with datacasting. Some schools in South Carolina were using it last year.

There are limitations to the technology that won’t allow it to replace the internet. For one, the datacasting is currently one-way and won’t allow students to send data back to schools. That means no video chats with teachers or access to email.

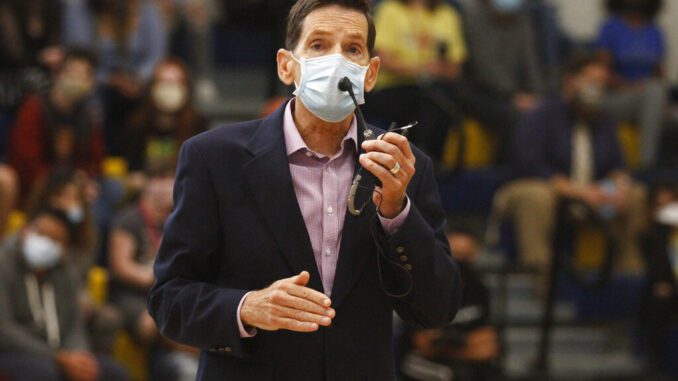

“Until fiber optic cables bring broadband internet to every corner of New Mexico, we’re going to need a patchwork of solutions, and it sure looks like datacasting could be one,” New Mexico Education secretary Kurt Steinhaus said.

Earlier this week, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham named an adviser for the newly formed state office of broadband. A deputy representing the adviser at the meeting said that in an optimistic scenario getting all New Mexico residents access to high-speed internet would take three years.

The pandemic left education officials around the world scrambling to make remote learning possible, often in areas with limited or no internet access. Some nations — including Mexico and Thailand — broadcast lessons on public television channels, but they didn’t set up ways to transmit files.

UNICEF has said globally about 131 million children have missed out on three-quarters of their in-person instruction since March 2020, and nearly 77 million of them have missed almost all of it.