We have this trinity of “holy” civic documents underlying our collective life together in America: the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution  and the Gettysburg Address.

and the Gettysburg Address.

We have the Fourth of July as our high-holy civic “Christmas” commemorating the birth of our republic through the Declaration. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address makes sure July 4 will be forever intertwined with Thanksgiving, which essentially is our civic “Easter” for its role in the resurrection of freedom for all Americans.

Thanksgiving should be celebrated more as a memorial and covenant to the “born again” America that Lincoln talked about at Gettysburg than solely being remembered for Squanto’s kindness towards the Puritans.

American history can be divided metaphorically into the “Old Testament” — life when slavery was allowed under the Constitution — and the “New Testament” under the amended Constitution after slavery had been defeated. It was at Gettysburg 158 years ago that Lincoln announced the philosophical and spiritual “Good News” for what America was going to become after the horrendous conflict was over.

Author Gabor Boritt wrote “The Gettysburg Gospel” to explore the profound religious undertones and themes easily recognizable to 19th century Americans, which Lincoln adroitly deployed in his understated, yet immaculate Gettysburg Address.

He gave his address on Nov. 19, one week before the first national day of Thanksgiving while suffering from variola, a mild form of smallpox. Two months earlier, he had declared the last Thursday of November “as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens” for the Union victory at Gettysburg.

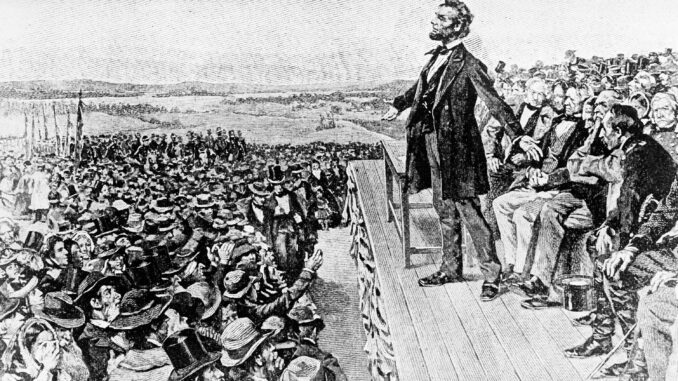

Lincoln was routinely derided as a hick from the Illinois sticks for his lack of formal education and awkward appearance and gait. But he knew exactly what he was doing when he delivered his 271-word speech around 3 p.m. on a clear crisp late autumn afternoon at the new Soldiers National Cemetery on the Gettysburg battlefield, still-bloodstained four months after the previous July 4 weekend battle.

Lincoln used every literary tool in his arsenal of memorized quotations, themes and rhythms from the King James Bible; every Shakespearean play and Pericles’ “Funeral Oration” to paint a sublime portrait of the new “Born-Again” America to come.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

“Fourscore and seven” was a familiar reference from Psalms 90. “Brought forth,” “conceived” and “shall not perish” in the closing line evoked biblical images of physical and spiritual birth, death and eternal life.

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

“But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

“The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.”

Lincoln wanted the American people to look beyond the horrors of war and recognize the “unfinished work” they would have to accomplish together as free people, both North and South, white and black alike, in order to form “a more perfect Union” “with malice toward none, with charity for all.”

Lincoln knew about an 1858 lecture by transcendental abolitionist minister Theodore Parker of Massachusetts, who wrote: “Democracy is direct self-government, over all the people, for all the people, by all the people.”

In Lincoln’s word construction, Parker’s observations became the closing line of one of the most powerful speeches in human history.

“It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Give thanks this Thanksgiving for the blessings of the rebirth of freedom in 1863. Pray for a new rebirth today. Amen.