The first thing Vince Lombardi told the Green Bay Packers when he became head coach was a deceptively simple lesson.

“Gentlemen,” he famously said. “This is a football.”

Six decades later, defenses still frequently get that basic fact of the game wrong.

During UNC’s win over Virginia last month, Sam Howell took the snap, turned and stuffed the ball into the waiting arms of Caleb Hood.

The freshman running back tried to make a move, but Virginia linebacker Noah Taylor had already broken through the line and hit him from one side. Taylor wrapped Hood up and threw him to the ground, landing on top of him.

As Taylor knelt astride Hood’s body, he took his arms and waved them in front of him, like a referee signaling “no good” on a shanked kick or incomplete pass.

His celebration was cut short, however, when he suddenly realized he was nowhere near the ball. Hood didn’t have it. Howell had kept it when he faked the handoff and was running it around the opposite end of the line.

Taylor jumped to his feet and tried to pursue the ball, but the play was over long before he got there.

A week later, late in Duke’s blowout win over Kansas, backup quarterback Jordan Moore faked a handoff to running back Jaylen Coleman. The Jayhawks’ defender, who, like Taylor, had also penetrated the backfield, grabbed Coleman around the neck and swung him.

He might have been flagged for a horse-collar tackle penalty —had Coleman actually had the ball. But Moore had kept it and was making his way downfield.

Whether it’s a run-pass option (RPO) or a straight play-action pass, the run fake has returned to football in a major way.

“I’ve always loved play fakes,” said Duke coach David Cutcliffe. Up the road, UNC offensive coordinator Phil Longo is also a big fan. The Tar Heels may run play action more than any other team in the ACC, and some of Howell’s biggest highlights have been long touchdown passes that were set up by a quick, but effective, play fake.

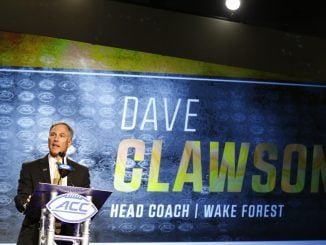

Across the state, Wake Forest’s Dave Clawson’s offense is built around the RPO, featuring a play fake (or “RPO mesh,” as they call it) that often seems longer than a Yankees-Red Sox game before the quarterback finally hands off the ball to the running back — or did he?

“One of the hardest things to do as a defensive lineman is, in play-action, to transition from playing run to pass,” Clawson explained. “It really slowed down pass rushes. It made defensive linemen play run before pass.”

That’s the goal of Howell and Longo’s play fakes as well — to slow down the defenders, perhaps for a step or two, perhaps for an entire phantom tackle. But if a defense is headed in the wrong direction, it buys time for the deep ball.

“We want to get linebackers sucked up,” said Duke assistant Zac Roper, who has coached both quarterbacks and running backs as well as serving as offensive coordinator. “Maybe get the secondary’s eyes in the wrong place, certainly, at times, get the secondary to step forward. Maybe if the secondary is really disciplined (and continues defending the pass instead of falling for the fake), maybe you get the linebackers to fit their gaps (come forward to the line to stop the run) and you get routes in between linebackers and secondary.”

It’s a game of inches, and normally the fakes are good for a step or two in the wrong direction. Occasionally, though, an offense gets the perfect storm and a defender begins to celebrate tackling a guy who isn’t carrying the ball.

“Rarely do you get a defender to completely bite and get into the line of scrimmage,” Roper said. “It’s great when you can do it. And when you can, that’s when you get balls behind the defense.”

The trick is … well, the trick. A quarterback needs to be able to fool a defense into thinking they actually got rid of the ball.

“I think that it’s a rhythm,” Cutcliffe said while stepping away from his podium to mime handoffs. “If you look at most really good quarterbacks that are great ball handlers. The run and the fake have the same tempo. And then Sam Howell has got really quick hands. He can get it out.”

He’s also a skilled actor, as are the UNC running backs.

“They (the defense) have to see what they would normally see on a handoff,” Roper said. “So the ball being into the belly of a running back. The eyes of the quarterback being into that mesh and really making that run fake look like run. So if a quarterback is trying to peek at coverage, you may not get the same run sale that you’re trying to get in order to do whatever you’re trying to do.”

Any great actor needs a supporting cast, and the quarterback gets help selling the fake from a very unlikely source — the offensive line.

“We want it to look and sound like run,” Roper said. “From an offensive line standpoint — low pad level, creating contact at the line of scrimmage.”

That’s what Duke linebacker Shaka Heyward says he uses to tell a true run from a fake.

“If I don’t get any pads popping, if I don’t see them coming off to kind of get somebody, then I’m not gonna bite on the run fake,” he said.

Heyward also isn’t worried about tackling the wrong guy.

“You always just want to do your job, your assignment. So get that squared away first,” he said. And if he’s assigned the running back, then tackling him is part of Heyward’s job. “So that’s not a big mistake. If you have to, you’d rather be safe.”

In the end, defending the play fake comes down to the same thing as running one successfully — attention to detail, the fundamentals.

Things like, “Gentlemen, this is a football.”