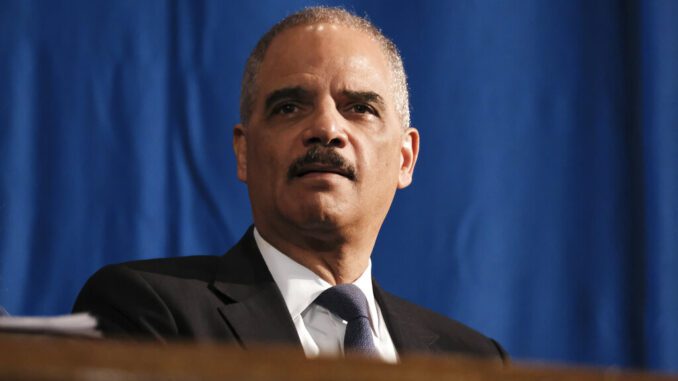

DURHAM — Activists at public hearings on redistricting are calling for “fair maps” and speaking against gerrymandering, but operatives connected to Eric Holder’s National Democratic Redistricting Committee are worried they are doing more harm than good to Democrats’ cause.

The maps, expected from the North Carolina General Assembly in October, will increase the state’s congressional representation from 13 seats to 14, due to 2020 census numbers showing the state’s growth relative to other states. Holder’s group is fighting to see that the new seat is not added to the Republican’s 8-5 advantage in the delegation.

Throughout September, North Carolinians are being given a chance to communicate their priorities for the new congressional maps during public hearings in each of the 13 current congressional districts. Members of the General Assembly’s Joint Select Committee on Congressional Redistricting are in attendance at these events to listen and note the comments.

The first hearing was held on Sept. 8 at Caldwell Community College in Lenoir, and the final one will be held on Sept. 30 at Fayetteville Technical Community College. NSJ was in attendance at the Sept. 15 Durham Technical Community College hearing. The bulk of the dozens of comments were from left-leaning activists venting anger at the legislators, calling for fair maps and denouncing gerrymandering. The speakers frequently noted court battles over the state’s congressional maps made after the last census, which had to be redrawn due to alleged partisan and racial gerrymandering.

But the comments being made at the events, according to Lekha Shupeck, state director for All On The Line, the grassroots organizing arm of the NDRC, were too vague and unhelpful.

“Y’all one thing I have to say — I am concerned that people are not making effective comments at public hearings — that they’re making comments that can be easily ignored by the redistricting committee,” said Shupeck in a Sept. 14 Twitter thread.

She went on to say that Republicans were making very specific comments about not wanting their counties split into two districts or not wanting their rural area paired with a city, comments which she believes will be useful “now and in future litigation.” She said left-leaning activists, however, need to be “making a very different kind of public comment than the vast majority of people are making at these hearings,” and instructed followers that “If you want to know how to make an effective comment, come to one of our trainings.”

Republicans at the legislature quickly fired back at Shupeck and Holder, with Sen. Ralph Hise of Spruce Pine, co-chair of the joint committee, saying, “Stop trying to sandbag the process. Let people say what they wish. He accused the NDRC of “‘Begging’ the Public to Parrot Their Canned Talking Points.” Hise’s press release also suggested that people should not be fooled into thinking NDRC and All On The Line are non-bias actors looking for simple fairness, since the stated mission in their IRS paperwork is to “favorably position Democrats for the redistricting process.”

Those speaking in Durham, while nearly united in their anger at gerrymandering and Republicans, were not united in their messaging, as Shupeck noted. Some favored eliminating the use of partisan and racial data to avoid the “targeting” courts alleged in past maps; others said without using this data, the process would be too blind and fair maps couldn’t be drawn. Some favored maintaining “communities of interest” and avoiding splitting them; others said packing these communities together would cause non-competitive districts. Some favored maintaining wholeness in counties and cities; others opposed this as a priority.

General Assembly Republicans announced in August that they are not going to consider partisan data at all in their maps, “for the first time in North Carolina history,” and instead will “use several other traditional, non-partisan redistricting criteria such as seeking to keep municipalities whole, avoiding splitting precincts, and keeping districts compact, in an effort to limit partisan considerations.”

Observers from all sides have noted that these non-partisan criteria favor Republicans at the moment, because Democratic voters are concentrated in cities. Republicans, who are more spread out across the state, have a strong advantage in the vast majority of counties, so Democrats generally run up their numbers in urban races and then lose everywhere else.

To create a map that would favor Democrats, it would have to break up the cities and create what some have called “pizza-slice” districts to dilute the advantage of GOP-leaning rural counties by adding some urban Democrats to each of the surrounding districts. But with provisions that keep cities and counties whole, this would not happen, and any map created would almost certainly favor Republicans.

When they are accused of partisan gerrymandering to get the current 8-5 maps, Republicans are quick to point to comments about the 2019 process from Democrats at the legislature, such as from current U.S. Senate candidate state Sen. Jeff Jackson (D-Mecklenburg), who said, “I feel as someone who has been a frequent critic of redistricting, I’m duty-bound to acknowledge these are the fairest maps and this was the fairest process to occur in N.C. in my lifetime,” and from state Sen. Natasha Marcus (D-Mecklenburg), who said, “I believe these Senate maps are as good as humans can draw.”

With Republican’s advantage on nonpartisan criteria in mind, Democrats are increasingly shifting to a call for evenness in the predicted future delegation, without as much focus on what process creates those results. In a state that is around 50-50 in voting behavior, Democrats argue the maps should create something closer to a 7-7 delegation, not 9-5, which would be the result if Republicans gained the new seat.