VATICAN CITY — A fraud and embezzlement trial over alleged mismanagement of the Holy See’s investments began Tuesday in Vatican City, with a once-powerful cardinal among the 10 defendants saying he remains “obedient” to Pope Francis, who stripped his privileges to bring him before the tribunal.

”He wanted me to be on trial, and I’m coming to the trial. I’m serene. I feel tranquil in my conscience,” Cardinal Angelo Becciu, one of two defendants who attended the largely procedural, seven-hour session, told reporters afterward.

Becciu, a former longtime Vatican diplomat, is charged with embezzlement, abusing his office and with pressing a monsignor to recant information he gave to prosecutors about the handling of disastrous real estate deal involving properties in London.

The 73-year-old prelate, who was elevated to cardinal by Francis in 2018 but later dismissed by the pope from his later post in charge of the church’s saint-making office, has denied any wrongdoing.

During the first day of the trial, defense lawyers lamented they hadn’t had time to digest about 28,000 pages of documents recently released by Vatican prosecutors. They noted that much of the evidence from the July 3 indictments hadn’t been made available to them, apparently due to logistical problems.

Chief Judge Giuseppe Pignatone agreed, setting the next hearing for Oct. 5. A former Rome chief prosecutor, Pignatone earlier had spent years investigating the Mafia in Sicily and criminal economic activity.

The Vatican, an independent city state, has a tiny courtroom, as well as its own jail. But to accommodate all the defendants, lawyers and journalists for what is the largest trial in the Holy See’s modern history, the case was moved to a hall that is part of the Vatican Museums.

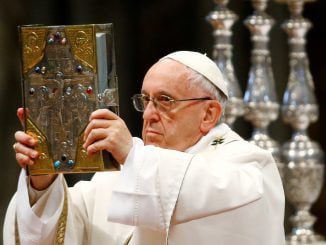

The makeshift courtroom is adorned only with a crucifix, and, just behind where the three-member prosecution team sits, a photo of Francis in his white robes.

Not waiting for a verdict, Francis has already removed Becciu’s rights as a cardinal. So Becciu showed up in court wearing a plain black clergyman’s suit and a large, pectoral cross instead of the prestigious red garb reserved for the so-called ”princes of the church.”

Asked by a reporter why he showed up for his day in court while most of his fellow defendants did not, Becciu said: “It’s important to be here.”

Also in court was Monsignor Mauro Carlino, who is charged with embezzlement and abuse of office. He was a top aide to Becciu when the prelate was a chief of staff in the Vatican’s Secretariat of State. The two men chatted during breaks.

All the defendants face prison or fines or both if convicted. They have denied wrongdoing.

Just less than three months ago, it would have been impossible for a cardinal to be in the dock in the Vatican City State, which has its own justice system and even a jail. But, as alluded to in Becciu’s comments, Francis had a law changed so that Vatican-based cardinals and bishops can be prosecuted and judged by the Holy See’s lay criminal tribunal as long as the pontiff signs off on it. Previously, Vatican cardinals could only be judged by their peers, a court of three fellow cardinals.

The defendants are alleged to have had a hand in actions that effectively cost the Holy See tens of millions of dollars in donations collected at Mass from rank-and-file Catholics. The prosecution contends that the heavy losses resulted from poor investments, dealings with shady money managers and purported favors to friends and family.

At the heart of the two-year probe is the London real estate deal approved by the Secretariat of State. An initial 200 million euros (now nearly $240 million) was sunk into a fund operated by an Italian businessman. Half the money went into the real estate venture in the swank Chelsea neighborhood, an investment that eventually cost 350 million euros. By 2018, the original investment was losing money, and the Vatican scrambled to find an exit strategy.

Among the defendants is Italian broker Gianluigi Torzi, whom the Vatican engaged to help it acquire full ownership of the London palazzo from another indicted money manager, who handled the initial investment in 2013. The Vatican contends it lost money on unwise investments.

The judge said Torzi alone had a “legitimate impediment” to attending the trial. His lawyers noted that Torzi cannot leave London, where he is based, because he is awaiting British judicial developments following an extradition request from Italian authorities in another financial probe.

Also absent was Cecilia Marogna, who was hired by Becciu as an external security consultant. Prosecutors allege she embezzled 575,000 euros in Vatican funds that Becciu had authorized for use as ransom to free Catholic hostages abroad. Marogna has contended that charges she ran up were reimbursement of her intelligence-related expenses and other money was her compensation.

Her lawyer told the court she couldn’t attend because an Italian intelligence agency is obliging her to secrecy and Marogna doesn’t want to violate that order.

Vatican law, as does the Italian legal system it partially mirrors, permits plaintiffs to join a trial in hopes of winning monetary compensation, to press for justice and to be able to address the court.

“This trial has a strong moral connotation,” said Paola Severino, a former Italian justice minister who represents the interests of the Holy See and the Vatican bank at the trial.