NEW YORK — The voice on the phone is steady and clear. “It is unnatural to kill anything,” the man says. “But once you’ve done it the first time, it becomes easier each time.”

That chilling insight comes from inside Red Onion State Prison in Virginia. The voice is owned by Lee Malvo, half of a two-man sniper team that killed 10 and terrorized the Washington D.C., region in 2002.

Malvo’s account of how he ended up shooting strangers while hiding inside a Chevy Caprice trunk is at the heart of “I, Sniper,” a superb documentary series on Vice TV that starts Monday. “I was a thief. I stole people’s lives,” Malvo told the filmmakers. “What inside me made that possible?”

The eight-episode series is a nuanced and expertly researched attempt to answer that question, with dozens of interviews, from relatives of the snipers and their victims, law enforcement, journalists and everyday people who encountered the pair.

But perhaps the most astounding interview is of Malvo himself: candidly revealing every detail of his horrific crimes from periodic phone calls behind bars.

“I, Sniper” producer Mary-Jane Mitchell coaxed Malvo to examine his life over 17 hours of calls that spanned years — all in 15-minute chunks, per prison rules.

“As you can imagine, trying to get to that place emotionally at 15 minutes at a time — when you never know when the next call is going to come in — is a dance that you have to do,” she said.

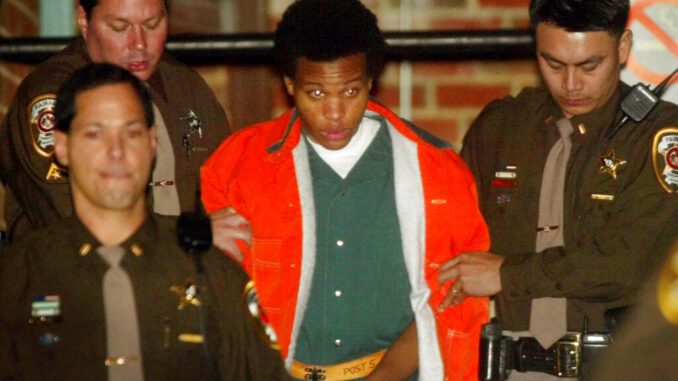

Malvo was 17 when he and John Allen Muhammad, then 41, went on their sniper spree. They picked off victims going about their daily business: shopping, getting gas and mowing the lawn.

He and Muhammad were convicted of two murders in Virginia and six murders in Maryland. Malvo was given life sentences without parole; Muhammad was sentenced to death and executed in 2009.

“I, Sniper” starts with a murder by Malvo in Tacoma, Washington, nine months before the Capitol sniper attacks, and follows the pair as they crossed the country, robbing and murdering along the way. The filmmakers used 911 calls, TV news footage and even X-rays to tell their stories.

Isa Nichols, the aunt of Malvo’s first victim, Keenya Cooke, has long shied away from projects that sought to sensationalize her family’s death, but the “I, Sniper” filmmakers won her over with their transparency, patience and ability to listen.

“They allowed me to honor my niece,” Nichols tells The Associated Press. “They really did a wonderful job. Letting me work through this process.”

Malvo claims he was a victim of manipulation by the older man. “Muhammad was master puppeteer,” he says in the film. “I was an instrument.” Muhammad had lost custody of his kids and Malvo said he wanted to punish the nation, planning on killing six to nine people a day. “The plan was psychological devastation,” Malvo says.

Mitchell had been in Washington, D.C., during the gunmen’s 23 days of terror and later corresponded with Malvo. Initially, she said, he “didn’t have the kind of insight and maturity to do the work for a film like this.” That changed about five years ago.

“I felt that he had done so much work on his own in solitary by the time we got to 2016 to try and understand — to own the harm that he’d done, to try and make some reparations — that he was in a moment where he was just really looking inward. There was no bravado in it. I thought it was a very genuine attempt to understand,” she said.

The 15-minute interviews with Malvo continued even as the filmmakers spoke to a wide variety of sources, including the man who sold the duo their car, Malvo’s teacher, a woman spared by the gunman, Mohammed’s ex-wife and Malvo’s mitigation specialist in court.

That meant the filmmakers could go back to Malvo to explain something a witness brought up or tease out a memory. In one remarkable moment, a robbery victim who survived five gunshot wounds wondered why he was picked. “Who was I to him?” he asks in the film. Malvo soon supplied the chilling answer: “Money. Training. And that’s it.”

“It was a living edit,” said John Smithson, the film’s creative director. “Normally an edit is a past tense process, cutting material that you’ve already shot. With this, a crucial creative element was coming in until we virtually locked the film.”

Nichols, who has written a book about her niece’s death, said the filmmakers’ extensive research led her to understand better the man who brought such sadness to her family.

“The things that they found out gave me more insight in terms of who this young man really was,” she said. “The research they did allowed me to see how Lee was no different than any other inner-city young male out in the street who doesn’t really have the guidance that they need to have.”

The filmmakers said they were always careful to not exploit the tragedy and include voices that were both sympathetic toward Malvo and not. “It was never, ever, ever seeking to exonerate him or forgive him. But we certainly sought to understand him in as much as we could,” said Smithson.

One person who won’t be seeing “I, Sniper” is Malvo. “He won’t be able to, I wouldn’t imagine,” said Mitchell. “He’s not overly concerned with seeing it. For him, it was something he felt he needed to do and he’s done it.”