WASHINGTON, D.C. — For 50 years the Minuteman missile has been armed and ready, day and night, for nuclear war on a moment’s notice. It has never been launched into combat from its underground silo, but this year it became the prime target in a wider political battle over the condition and cost of the nation’s nuclear arsenal.

Minuteman was not intended to last half a century, so it’s overdue to be replaced or refurbished. Some see this as a moment to push for scrapping it altogether, abandoning one leg of the traditional nuclear “triad” — weapons that can be launched from land, sea and air. Most in Congress favor keeping the land-based leg by replacing Minuteman with a new missile; President Joe Biden’s position is not yet clear.

The outcome of the fight likely will steer nuclear policy and strategy for decades to come. It could influence how U.S. allies in Europe and Asia view the reliability of America’s nuclear “umbrella” — the security net that has allowed most of them to forgo developing nuclear weapons of their own. Some argue that it could make the difference between war and peace in an era of rising Chinese military power.

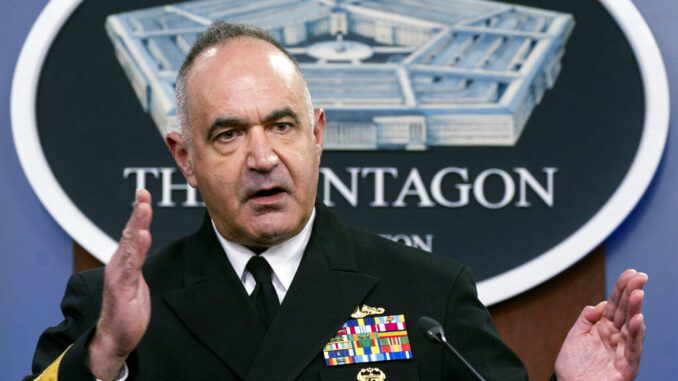

Navy Adm. Charles Richard, who as head of U.S. Strategic Command is in charge of nuclear warfighting plans, says Minuteman is so old that Air Force technicians have had to perform magic to keep it fully functional while coping with severely limited spares for components such as missile launch switches.

“I’m afraid there’s a point where they won’t be able to pull the rabbit out of the hat and the system won’t work,” he told a House hearing April 21. Asked later by a reporter if he meant Minuteman had become unreliable, Richard said it’s safe and dependable for now but with “no more margin” for delay in replacing it.

Stephen Schwartz, a nonresident senior fellow at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, says Richard’s statements are reminiscent of alarming claims made during the Cold War about needing new weapons.

“Time and again, officials have warned us ‘the sky is falling,’ and it is never true,” Schwartz said. “Congress should critically examine the historical record and apply some healthy skepticism to such testimony.”

Richard applauds a bipartisan push in Congress to preserve and modernize the entire nuclear arsenal at a cost, depending on how you define it, of more than $1 trillion. Opponents include a former defense secretary, William Perry, who has become an outspoken critic of Minuteman. The Pentagon’s current leader, Lloyd Austin, has been publicly noncommittal on Minuteman but favors preserving the nuclear triad.

The consensus in Congress is that age is eroding the three main pillars of U.S. nuclear strength — long-range bomber aircraft like the 1960s-era B-52, submarines armed with Trident ballistic missiles, and the Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs. Relatively few oppose building new-generation bombers and submarines. The most contentious debate is over whether, when and how to replace Minuteman.

Arguments over Minuteman boil down to this: Given its age and the nuclear challenges posed by Russia and China, should it be phased out in favor of a new-generation ICBM? Or should it be refurbished at lesser cost, to be replaced later? Or should it be phased out, period, with no replacement?

The debate reveals a longstanding American divide. On one side is the view that ICBMs are indispensable to the strategy for deterring any adversary from attempting a nuclear attack upon the United States or its allies. A key piece of the argument is that ICBMs in their 400 underground silos in five Great Plains states act as a “warhead sink,” or sponge, to absorb the first blow in a nuclear war; the argument is that an attacker would need to expend so many weapons destroying these silos that he would see little chance of winning and thus would be deterred from attacking in the first place.

The opposing view is that ICBMs are overkill, given the large amount of firepower in the more elusive sea- and air-based segments of the nuclear arsenal, and that ICBMs make nuclear conflict more likely because an American president might feel compelled to launch one upon a warning of attack that turned out to be a false alarm. Once it’s launched from its silo, an ICBM cannot be recalled.

These differences are more stark in light of expected stagnant defense budgets.

Among those eager to build a successor to Minuteman, some see political opportunity in its occasional slipups. For example, when a routine flight test was aborted shortly before launch last week, Rep. Don Bacon tweeted that the incident was evidence that Minuteman must be modernized “before it’s too late,” although the Air Force has yet to determine what triggered the abort. Bacon is a Republican from Nebraska — home to Strategic Command headquarters and to some Minuteman silos.

Biden has not publicly addressed the issue. In March the White House released interim national security guidance promising to “take steps to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy” but offering no details.

As a candidate in 2019, Biden said he believed the nuclear arsenal could be modernized for less than the projected $1 trillion price tag, but was not specific. Some interpreted this as him doubting the need for new ICBMs, but thus far his administration has given no indication of abandoning the plan it inherited to replace Minuteman with a successor dubbed the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent, starting in 2029.

Last September, Northrop Grumman won a $13.3 billion contract to develop the successor. The estimated cost of fielding the full system is $95 billion, rising to $264 billion counting sustainment costs over the weapon’s expected lifetime into the 2070s.

Signs of the Biden administration’s nuclear path may emerge in the 2022 budget to be presented to Congress soon. The Pentagon also plans a formal review of its nuclear “posture,” which likely will affirm the need for nuclear modernization but might not decide certain details.

Rep. John Garamendi, a California Democrat, is unconvinced by arguments that Minuteman is just too old to undergo a life extension — a refurbishment to keep it in service for decades to come.

“I need a new one,” Richard, the Strategic Command chief, retorted in a heated exchange with Garamendi last month.

Richard says there is no room for delay. But a new report by the Government Accountability Office suggests delays are almost inevitable. It concluded that every part of nuclear modernization “faces the prospect of delays” due to limitations in the workforce, infrastructure and supply chain.