WINSTON-SALEM — Early in the coronavirus pandemic, learning the true extent of the virus’ spread was a critical component of decisions made for treatment, limiting the spread and learning how many people had truly been infected.

On April 13, 2020, the N.C. General Assembly gave $100,000 in seed funding towards an initiative Wake Forest Baptist Health and Atrium Health began to test a representative sample of the population. At the time, Senate Leader Phil Berger (R-Eden) said the study would help fill a critical data gap.

Nearly one year later, the study has enrolled over 23,000 individuals to log daily symptoms, and nearly 11,000 of those enrolled have taken at least one antibody test.

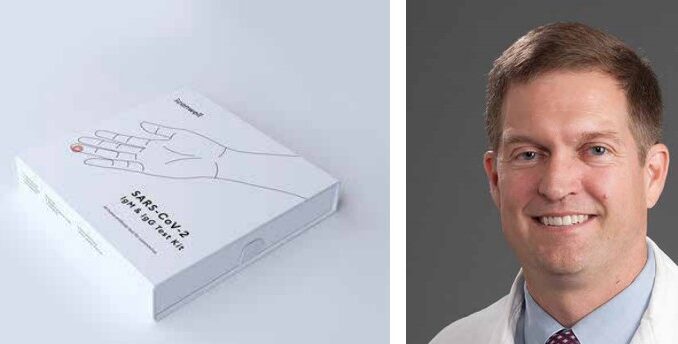

Dr. John Sanders, chief of infectious diseases within the internal medicine section at Wake Forest Baptist Health, has helped lead the study. A graduate of Tulane University’s School of Medicine who earned his undergraduate degree from N.C. State, Sanders told North State Journal in an interview that the antibody study has produced some answers, but also many more questions, about COVID-19 in the past 11 months.

“We entered this study with some basic assumptions about being able to look at antibodies and determine immediately the scope of the epidemic in the region and be able to track that epidemic with the antibodies,” said Sanders. “It’s been a real challenge.”

Antibodies are proteins created by a person’s immune system soon after they have been infected or vaccinated. They help fight off infections and can protect the person from getting that particular disease again, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Sanders said the Community Research Partnership study has been unique in that it has been an ongoing, enrollment-based, repeated sample where scientists can see trends over time. However, he says, the study also has to take into account mathematical adjustments based on participants dropping out, joining at different times, not logging symptoms or logistical issues related to tests.

“You end up taking the data over time and putting it into mathematical models and adjustments. We haven’t made that public, which makes it hard for someone just checking the website to make sense of it.”

Sanders added that many of the antibody studies performed and published have not lined up with projected models of COVID-19’s spread, which makes being able to see trends over time important. But they must still make some mathematical adjustments.

“There haven’t been many studies of large numbers and repeated checks like ours. Our data is accumulating very quickly, and will be more important in the next phase of the epidemic,” he says.

Antibodies are just one part of our immune response to viruses, Sanders said, adding that there are many more that are important. He said scientists are still determining if there are biological markers that correlate or predict immunity.

“Don’t assume you’re getting all of your immunity from this one test,” he says. “There is good evidence to suggest if you have that [antibody], you got some good protective immunity. We don’t have good evidence that if you don’t have that antibody, did you lose protective immunity? We’re still trying to work that out.”

He added, “When you get national infection, you see the spike protein but also the rest of the virus. You’re making a broader portfolio of immune response.”

Sanders also outlined some of the things he’s learned about COVID-19 he said he likely wouldn’t have known if he weren’t leading the study.

He said he was surprised at how quickly an antibody test can go from positive to negative.

“That doesn’t mean people have lost immunity, it just means using a relatively simple test, how quickly we are no longer able to detect it. Every test has a certain threshold and protection level. Their antibody may still be there, but it’s circulating a level below detection.”

“We’ve shown using a very simple at-home test, about 50% of people positive after a natural infection become negative on a subsequent test in a little over a month,” he said.

Sanders said this is called “antibody decay.”

This is part of the reason, he says, the study and the World Health Organization (WHO) have had a hard time using antibody tests to determine who may have been infected by COVID-19.

He went on to say that the General Assembly-funded cohort within the study use a simpler, but not as sensitive, test. They also have a CDC-funded area using a test that’s highly sensitive but takes more effort on the part of the participant.

“We are in the process of collecting data on how much longer this group can detect antibodies versus the more convenient test,” said Sanders.

Another aspect Sanders mentions when discussing COVID-19 is that he, scientists, and everyone must think about the virus differently, because we saw it in a wave, not a trickle.

He said that COVID-19 is an “interesting” virus partly because they’re learning, and seeing it, all at once.

“The human condition is that we try to make patterns out of things. So if I see three COVID patients with certain conditions, I think, ok, COVID presents with this… I’m not sure we can say that about this virus yet. I’m not sure we’ve gone through enough cycles to say what the seasonal implications are.”

He pointed to an example with influenza, and how recent years have found more summer influenza as diagnostic tests have gotten better.

“Truthfully, we have to guard against making dogmatic statements like ‘this virus is appreciably different than other respiratory viruses,’ because we haven’t had it long enough. There are other coronaviruses that annually cause colds, respiratory infections, and we consider them ‘minor viruses.’ But they’re not minor viruses. There are people every year that get very sick from them,” Sanders said.

“So, is COVID-19 that different? Partly, we think that because we saw so much all at once. If we go back 100, 150 years, the last time it popped out of an animal and infected humans, we might think that as well. So why have we still seen so much COVID? It’s because we have some degree of population protection to those other viruses and that is what drives the efficiency of spread so low. We did not have base population immunity to COVID-19 or existing immunity to drive the spread down,” he added.

Sanders also made the case for reaching a level of herd immunity, or population protection, soon.

“I did not expect us to have effective vaccines within the time frame we’ve been able to get them. So thank you to the scientists and government choices. I first thought it would take 2-4 years to get a half-decent vaccine and 1-3 years of natural infection and attenuation,” Sanders said. “I predicted we’d see this cycle and become similar to other respiratory viruses and cause colds and infections and for a few of us, we’d end up with a viral pneumonia. That’s what we see with other human coronaviruses, and respiratory viruses. Now, I’m having to reconsider that because we have great vaccines.”

Sanders said if vaccinations are pushed out broadly enough, COVD-19 can be suppressed to the point where it is sporadic, and not an annual event, even if it never goes away completely.

“As viruses circulate, they get weaker. To personify it, their intent is to get in us, replicate and spread to others. The virus doesn’t want to kill us quickly. They would rather us sputter and cough and spread that virus to other people. We saw very low levels of antibodies in the spring and summer, and then they really went up high over the holidays. Combined with vaccinations, we’re moving very quickly into where we are close to providing some population protection. Fortunately after a year of natural infection and vaccines, we are approaching hopefully a protective level of population immunity,” he said.