WELLINGTON, New Zealand — The leader of the University of the South Pacific and his wife were asleep at their Fiji home when a ruckus awoke them around midnight.

About 15 plain-clothed government agents had surrounded their house in the capital Suva, Vice-Chancellor Pal Ahluwalia said. After an argument at the door, four of the agents chased him through the house as he frantically tried to use his phone, he said. The agents confiscated all their devices, even their smart watches, and gave them minutes to pack.

The professor had vowed to root out corruption since beginning his job two years earlier at the university, which is considered a beacon for regional cooperation. Now, he’s at the center of a bitter dispute threatening to tear apart South Pacific regional relationships.

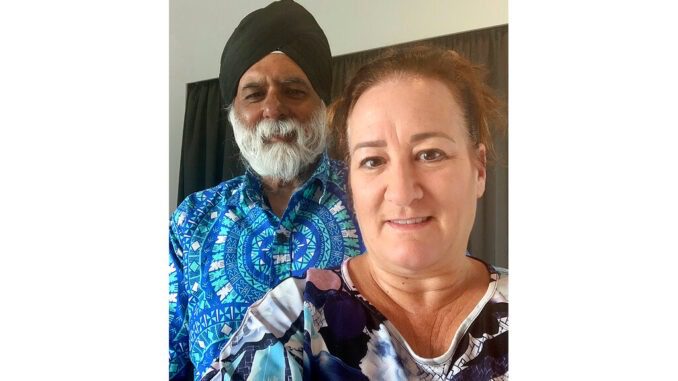

In his haste to meet the agent’s demands, Ahluwalia, who is diabetic, forgot some of his medicine. He and his wife, Sandy Price, a lecturer in nursing and midwifery at Fiji National University, were driven across the island to the international airport, put in a waiting room and bundled onto a plane just before 10 a.m. Thursday, with their devices returned to them as they left. About 10 hours after they were awakened, they were deported to their home country, Australia.

“We were in shock. We’re still in shock,” Ahluwalia said Friday in a phone interview with The Associated Press from his quarantine hotel in Brisbane. “We’re figuring out that whistleblowers aren’t treated well in Fiji.”

Their deportation was a dramatic escalation in a management dispute at the South Pacific’s top educational institution. Serving more than 28,000 students, the university is jointly owned by 12 countries, which each have their own campuses. The university is unusually structured for the scattered region that stretches over a geographic area three times the size of Europe.

Ahluwalia, who got his doctorate from Flinders University in Australia and was once a professor at the University of California, San Diego, said he became concerned about corruption soon after he started at USP. In March 2019, he submitted an 11-page report, along with hundreds of pages of evidence, to the university council’s executive committee.

The report documents a raft of extraordinary allegations: One manager’s salary increased more than eightfold over nine years, and an institute director was paid his own salary plus half the salary of an unfilled deputy position. It documented how one official took 28 days of paid professional development leave over six weeks and later was paid for another 117 such days.

By shaking up the university, Ahluwalia found himself in conflict with other administrators, some of whom have deep ties with Fiji’s government. In particular, Ahluwalia clashed with Pro-Chancellor Winston Thompson, a former Fijian diplomat.

Thompson, who could not immediately be reached for comment, told radio station RNZ last year that the university had been plagued by a governance crisis and that the management wasn’t fulfilling its duties. A committee led by Thompson briefly suspended Ahluwalia last year before he was reinstated to his role by the university council.

Jonathan Pryke, the director of the Pacific Islands Program at the Lowy Institute, an Australian think tank, has followed the dispute closely but was taken aback by this week’s developments.

“The whole thing is shocking, and the repercussions will be felt for years to come,” Pryke said. “I hope USP isn’t fatally damaged.”

He said not all the information has been made public, but it seems Ahluwalia had the right intentions.

“He could have played his cards better, given the cultural environment,” Pryke said. “He was trying to clean things up, and clearly pushed too hard. The old guard has enough domestic political backing to turn this thing into a real fight. Now they’ve gone nuclear.”

Fiji’s government is led by Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, who initially seized control in a military coup before being democratically elected. It said both Ahluwalia and his wife had to leave because they violated an immigration law that says foreigners cannot breach the peace, public morality or good government of Fiji.

“As a sovereign nation, Fiji will continue to enforce a zero-tolerance policy towards any breaches of its immigration law,” the government said.

The government’s statement has prompted more than 1,000 responses on Facebook, with many Fijians asking for specifics about what the couple did wrong. But the government hasn’t elaborated.

Pryke said Fiji tends to see the university as a national institution because it’s based there and its largest cohort is Fijian students. He said Bainimarama and his colleagues are likely frustrated they can’t exert total control. But he said other countries view it much more as a regional institution and are watching on with consternation.

He said the timing of the deportation couldn’t be worse, as the region has also been scrapping over the leadership of the Pacific Islands Forum, another organization which relies on regional cooperation.

Australia and New Zealand, which provide some funding for the university, have so far offered only bland responses.

“Look, there have been a number of issues in relation to the University of South Pacific, which have been the topic of much discussion among Pacific leaders and Pacific countries,” said Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison on Friday. “I’m not going to say anything here that would seek to add to or seek to complicate that.”

Meanwhile, Ahluwalia remains defiant. He said that while Fiji has forced him to leave it can’t force him to relinquish his job, which he intends to continue doing. But that remains uncertain. He was locked out from a virtual meeting of the university council on Friday and awaits his fate.