Growing up in Atlanta, I spent a lot of warm summer nights during the 1970s going to the ballpark with my homeroom buddy Steve Fritts to watch the Braves play baseball.

Being a Braves fan wasn’t as much fun or as cool back then as it is now.

The team was terrible, losing 90 or more games five times during the decade. But tickets were cheap and plentiful, it only cost a quarter to ride the MARTA bus to the stadium, and teenagers were afforded much more freedom from their parents than they have today.

The team was terrible, losing 90 or more games five times during the decade. But tickets were cheap and plentiful, it only cost a quarter to ride the MARTA bus to the stadium, and teenagers were afforded much more freedom from their parents than they have today.

Even though those Braves were usually eliminated from pennant contention by Memorial Day, there were still two compelling reasons to go watch them play beyond the fact that it gave us something to do.

Phil Niekro and Hank Aaron.

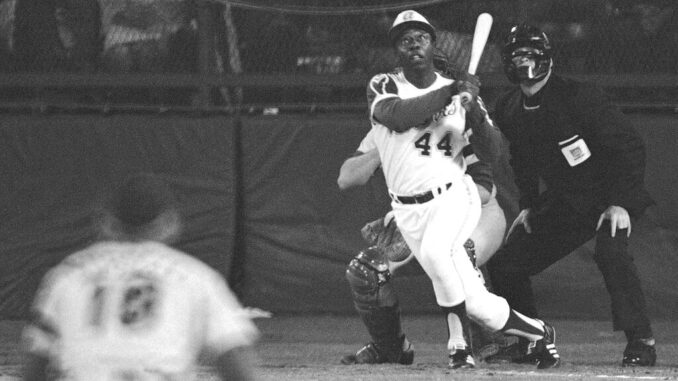

The former was a workhorse pitcher whose baffling knuckleball gave the team a chance to win whenever he was on the mound. The latter was capable of making history every time he swung the bat as he chased Babe Ruth to become baseball’s all-time home run king.

Sadly, both heroes from my childhood — along with longtime Braves broadcaster and fellow Hall of Famer Don Sutton — have passed away over the past few weeks.

Aaron’s death last Friday was especially heartbreaking,

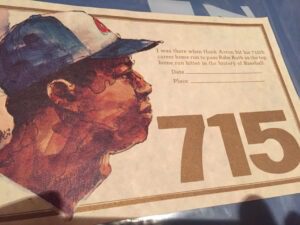

I still have vivid memories of April 8, 1974, the night the man known as “The Hammer” passed Ruth by hitting his 715th career home run.

Most nights, my friends and I were able to sit anywhere we wanted in the nearly empty stadium because of low attendance. Usually that meant sitting directly behind home plate or strategically fanned out along one of the foul lines poised to chase foul balls.

This time, however, we were relegated to the highest reaches of the upper deck. That is until most of the 55,000 in attendance headed home shortly after Aaron broke the record.

Because we were sitting in left field and had a somewhat obstructed view, I didn’t actually see the ball go over the fence. But the roar of the crowd and the fireworks that went off as the great man circled the bases left no doubt as to what had happened.

Thankfully, I thought enough to keep the commemorative certificate they handed out as everyone was leaving the stadium.

As awe-inspiring an event as it was at the time, it wasn’t until years later — after Aaron began to publicly disclose the details of what he went through during his home run chase — that I fully understood the magnitude of his accomplishment and the courage it took for him to pursue it.

It also put a much different focus on another childhood memory of Aaron.

This one happened after a random game during the summer of 1973, a time in which it no longer seemed a matter of if he’d catch The Babe, but rather when it would happen.

This one happened after a random game during the summer of 1973, a time in which it no longer seemed a matter of if he’d catch The Babe, but rather when it would happen.

One of our postgame rituals was to hang around the tunnel where the players left the stadium so we could get autographs of our favorites.

Aaron, of course, was the biggest prize.

The problem was that unlike the other players, the team’s brightest star would already be in a car as he left the stadium.

We thought he was simply being aloof. As it turns out, his efforts to avoid us were motivated by the constant stream of hate mail and death threats he and his family were receiving from racists upset that a black man was about to break one of the game’s most revered records. One set by an iconic white man.

Imagine then, the uneasiness Aaron must have felt the night my friend Steve — noticing who was sitting in the back seat — thrust the ball and pen he was holding into a half-open window while the car was stopped to let a group of autograph seekers clear its path.

Steve eventually got the autograph, but not before running about 200 yards alongside the car as it began driving away.

That incident was benign compared to the sight of two fans charging onto the field to congratulate him a year later during his historic 715th home run trot.

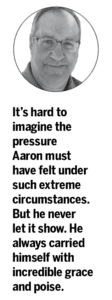

It’s hard to imagine the pressure Aaron must have felt under such extreme circumstances. But he never let it show. He always carried himself with incredible grace and poise.

That was his nature.

Whether it was his play on the field, which was never truly appreciated until late in his career, his involvement with the civil rights movement, his groundbreaking work with the Braves front office, his performance as an ambassador to the game he loved or the way he reacted to Barry Bonds’ controversial breaking of his home run record, Aaron did it with class, humility and a quiet confidence that served as an example to all.

Especially a once-young baseball fan who now realizes how lucky he was to be a Braves fan growing up in Atlanta during the 1970s.