Stick to sports.

This year’s Newcomer of the Year shouldn’t be eligible for the honor. The farthest thing from a newcomer, it’s been around forever. It just tends to get shouted down and ignored when it begins to make headlines.

Usually with a line like, “Stick to sports.”

The Brooklyn Dodgers didn’t stick to sports in 1947 when they signed a kid named Robinson and changed the world. Muhammad Ali and a host of other athletes in the 1960s didn’t stick to sports either, making their views on the war in Vietnam and social issues in the U.S. known. More recently, LeBron James and Colin Kaepernick have refused to stick to sports, earning public scorn — and in the latter’s case, banishment — for the decision.

Throughout the years, athletes have been in a precarious position — among the most recognizable and respected people in the public eye but unable to use their voice to help improve society.

Because they should stick to sports.

2020 was the year that all changed. Perhaps it was because sports were taken away from several months. After a lifetime of daily updates, transactions and rumors, suddenly, it all went away. And if we can’t depend on sports, the reasoning went, then why should we have to stick to them? And so we didn’t. Everyone — athletes, journalists, fans, teams and leagues — was ready to speak out and make their feelings, beliefs and causes known.

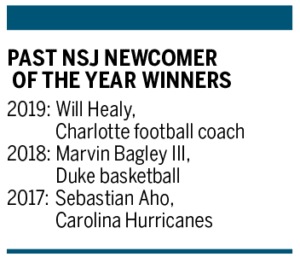

So, when the games finally returned, our choice was clear: Social justice in sports, or, perhaps more accurately, the acceptance of social justice in sports, is North State Journal’s Newcomer of the Year for 2020.

The movement for social justice, which filled the streets of our cities across the state and country, touched every area of the sports industry.

Teams took knees before games. The NBA played on a court displaying the message “Black Lives Matter,” and players wore social justice messages in place of nameplates on their jerseys.

Basketball teams in the state — most noticeably Duke and North Carolina — adopted the NBA practice, wearing social justice plates urging “unity” and “equality” on their jerseys. UNC’s football team also wore social justice nameplates for their game against Notre Dame.

It was more than just a patch or sticker on the floor, though. In large numbers, players took to the streets themselves to help support protests.

Duke sophomore Wendell Moore Jr. organized a march in his hometown of Charlotte. Back on campus, Duke assistant Nolan Smith took on an active role, helping to organize a campus-wide demonstration. Coach Mike Krzyzewski, often rumored to be conservative-leaning in politics, was extremely outspoken in favor of the Black Lives Matter movement and organized a midseason tournament involving HBCU Howard University.

The Carolina Panthers cut ties with a longtime sponsor — home security firm CPI, which had featured former coach Ron Rivera, former linebacker Luke Kuechly and current running back Christian McCaffrey in their TV commercials — when its CEO spoke out against the movement.

The Panthers also took down the statue of former owner Jerry Richardson that had stood in front of the stadium. Richardson was forced to sell the team amid accusations of racism and sexism.

Michael Jordan, who once defended staying out of social justice debates because “Republicans buy sneakers too,” announced that his Jordan Brand shoe and apparel company would be donating $100 million to organizations that promote racial equality and social justice. The money will be distributed over the next 10 years with the stated goal of “ensuring racial equality, social justice and greater access to education.”

“Black lives matter,” he said. “This isn’t a controversial statement. Until the ingrained racism that allows our country’s institutions to fail is completely eradicated, we will remain committed to protecting and improving the lives of black people.”

Jordan also crossed sports boundaries and became the first black principal owner in the NASCAR Cup Series, bringing diversity to a sport that sorely needed it. This was also the year that NASCAR banned Confederate flags from its events.

One of the sport’s few black drivers, Bubba Wallace, found himself at the center of social justice’s arrival to NASCAR, when a member of his team found a noose hanging in their assigned garage at Talladega.

In a moving display of support, the other drivers and crews walked behind Wallace prior to the race that weekend, helping push his car to the starting line. Along with the other 39 drivers and their teams, North Carolina NASCAR legend Richard Petty walked alongside his driver. The 82-year-old King made a rare public appearance in support of Wallace, releasing a powerful statement of how “enraged” he was and calling the noose a “despicable act.”

In a moving display of support, the other drivers and crews walked behind Wallace prior to the race that weekend, helping push his car to the starting line. Along with the other 39 drivers and their teams, North Carolina NASCAR legend Richard Petty walked alongside his driver. The 82-year-old King made a rare public appearance in support of Wallace, releasing a powerful statement of how “enraged” he was and calling the noose a “despicable act.”

An FBI investigation found that the noose was not directed at Wallace, leading to social media backlash calling the event a “hoax.”

In previous years, that might have been enough to send social justice back to the shadows, but, in 2020, Wallace and the increasingly diverse organization stood strong against the criticism.