On Dec. 24, 1776, a beleaguered General George Washington was looking for some way to inspire his Continental troops after suffering crushing defeats in New York. His undermanned Continental Army was facing the British army, strengthened with Hessians, under the command of General William Howe, encamped across the Delaware River in Trenton, New Jersey.

On Dec. 24, 1776, a beleaguered General George Washington was looking for some way to inspire his Continental troops after suffering crushing defeats in New York. His undermanned Continental Army was facing the British army, strengthened with Hessians, under the command of General William Howe, encamped across the Delaware River in Trenton, New Jersey.

It was cold and snowy; his troops lacked provisions and many of them were about to leave the army when their enlistment was up on Dec. 31. It was Christmastime and the last thing they wanted to do was embark on a secret attack across an icy river in the dead of night on Christmas Eve.

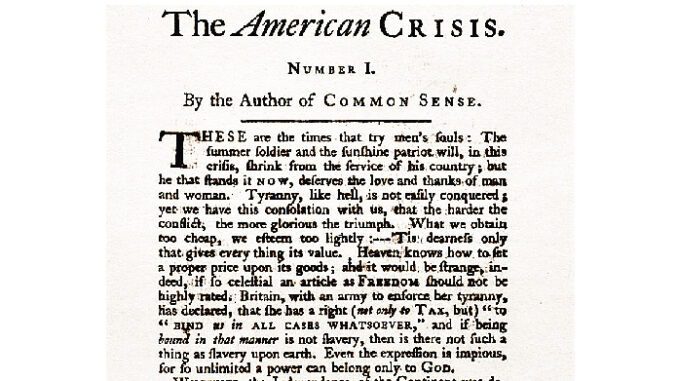

General Washington found the inspiration needed to rouse his troops in “The American Crisis,” a pamphlet published five days earlier by Thomas Paine. Paine’s “Common Sense,” published earlier in the year on Jan. 9, had been the spark that lit the flame of independence from Great Britain six months before the Declaration of Independence.

General Washington ordered the 3400-word pamphlet to be read aloud at McConkey’s Ferry to his troops, which included future American office-holders Supreme Court Justice John Marshall, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, President James Monroe and Vice-President Aaron Burr.

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.

“Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value…

These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.

“Britain, with an army to enforce her tyranny, has declared that she has a right (not only to tax) but ‘to bind us in all cases whatsoever’ and if being bound in that manner, is not slavery, then is there not such a thing as slavery upon earth. Even the expression is impious; for so unlimited a power can belong only to God….

“I have as little superstition in me as any man living, but my secret opinion has ever been, and still is, that God Almighty will not give up a people to military destruction…who have so earnestly and so repeatedly sought to avoid the calamities of war… Neither have I so much of the infidel in me, as to suppose that He has relinquished the government of the world, and given us up to the care of devils; and as I do not, I cannot see on what grounds the king of Britain can look up to heaven for help against us: a common murderer, a highwayman, or a house-breaker, has as good a pretense as he…

“(I)n the fourteenth century the whole English army, after ravaging the kingdom of France, was driven back like men petrified with fear; and this brave exploit was performed by a few broken forces collected and headed by a woman, Joan of Arc. Would that heaven might inspire some Jersey maid to spirit up her countrymen, and save her fair fellow sufferers from ravage and ravishment!

“I thank God, that I fear not. I see no real cause for fear. I know our situation well, and can see the way out of it…Look on this picture and weep over it! and if there yet remains one thoughtless wretch who believes it not, let him suffer it unlamented.”

That Christmas Eve night, after adopting the motto “Victory or Death,” the newly-inspired troops crossed the Delaware River and attacked a sleeping, and probably slightly inebriated, Hessian garrison at Trenton on Christmas Day to provide the first real victory for the Revolutionary Army in the War for American Independence.

Times may change. Americans will always have days when our souls are tried.

The only thing that matters, that which history will remember, is how we, as individual Americans, respond to such travails.