Airbnb proved its resilience in a year that has upended global travel. Now it needs to prove to investors that it sees more growth ahead.

The San Francisco-based home sharing company made a triumphant debut on the public market Thursday, with its shares more than doubling in price to open at $146. Airbnb had priced its shares at $68 apiece late Wednesday. The shares are trading on the Nasdaq Stock Market under the symbol “ABNB.”

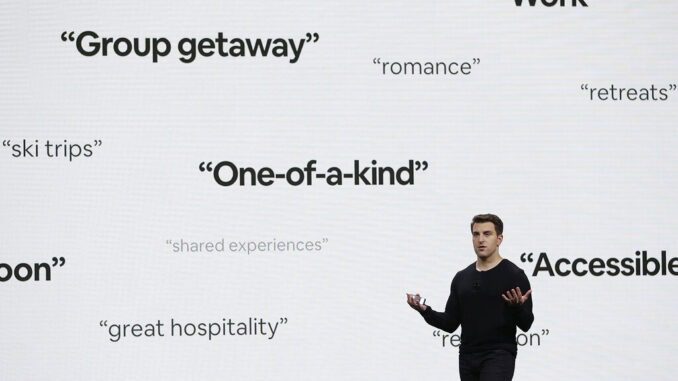

Instead of the traditional ringing of the bell prior to the trading day, Airbnb presented a video of Airbnb hosts from around the world ringing their doorbells. In a video message, CEO Brian Chesky also thanked the millions of guests who have stayed at its listings.

“You gave us hope that the idea of strangers staying together, in each others’ homes, was not so crazy after all,” Chesky said. “Airbnb is rooted in the fundamental idea that people are good and we’re in this together.”

Airbnb raised $3.7 billion in its offering, making it the biggest U.S. IPO this year, according to Renaissance Capital, which tracks IPOs. The company had initially set a price range of $44 to $50 for it shares, but raised that to a range of $56 to $60 earlier this week indicating rising investor demand.

Airbnb’s listing comes a day after another San Francisco-based company, DoorDash, soared through it initial public offering, the second largest after Airbnb’s. DoorDash’s stock jumped 85.8% to close at $189.51. The meal delivery app raised $3.4 billion with its offering.

Airbnb wants to add more hosts and properties, expand in markets like India, China and Latin America and attract new guests.

First, it will need to recover. Airbnb — which has never posted an annual profit — said its revenue fell 32% to $2.5 billion in the first nine months of this year as the coronavirus forced travelers to cancel their plans. The company delayed its IPO — initially planned for the spring — and funded operations with $2 billion in loans. In May, Airbnb cut 1,900 employees — or 25% of its workforce — and halted programs not related to its core business, like movie production.

But in the months since, Airbnb’s business rebounded faster than hotels as travelers felt safer booking private homes away from crowded downtowns during the pandemic. In Miami, for example, short-term rental occupancy reached 83% in October, while average occupancy for hotels was 42%, according to STR, an accommodations data firm.

Airbnb said the number of nights and experiences booked, which plummeted 72% in April compared to year-ago levels, were down 20% in September. Airbnb debuted experiences — from cooking classes to surfing lessons — in 2016.

Airbnb now has 7.4 million listings, from castles to treehouses, in 220 countries. They are operated by 4 million hosts. The company controls around 39% of the global short-term rental market, according to Euromonitor. It’s the market leader in Europe but trails VRBO, a vacation rental company owned by Expedia, in North America.

Looking ahead, Airbnb thinks it could see a surge in business from people who are able to work remotely.

“We believe that the lines between travel and living are blurring, and the global pandemic has accelerated the ability to live anywhere,” Airbnb said in a recent financial filing.

It could also expand its offerings further into boutique hotels, as it signaled with its 2019 purchase of last-minute hotel room supplier Hotel Tonight.

Still, Airbnb acknowledges it will be difficult and expensive to attract new hosts and guests. Its revenue growth rate was already slowing in the years leading up to the pandemic.

“I do think the company will benefit from the pent-up travel demand once the vaccine is widely distributed, but why would someone want to buy into a travel-related, unprofitable business with slowing growth?” said Scott Rostan, the CEO of Training the Street, which advises Wall Street analysts.

Airbnb was born 13 years ago in the San Francisco apartment shared by Brian Chesky — now the company’s CEO — and Joe Gebbia, who leads its design studio and Airbnb.org, its charitable arm.

Chesky and Gebbia were looking for a way to subsidize their apartment. When they learned a design conference was coming to town and hotels were full, they set up a website — AirBedandBreakfast.com — and rented out air mattresses. They got three takers. In 2008, they formed a company with Nate Blecharczyk, a software engineer.

Home sharing wasn’t new. VRBO was launched in 1995. Booking.com, another older rival based in Amsterdam, mainly offers hotel rooms but has also branched into vacation rentals.

What Airbnb did differently was focus on affordability, letting hosts rent out spare rooms and sofa beds, said Tarik Dogru, an assistant professor in the Dedman College of Hospitality at Florida State University who studies Airbnb. Guests strayed further into neighborhoods than they would if they stayed at a hotel.

“Airbnb offered that feel of authenticity for those who are looking for it,” Dogru said.

That has sometimes been a problem. The company has angered some cities, which accuse it of promoting overtourism and making neighborhoods less affordable by taking housing off the market. Los Angeles, Paris and even Airbnb’s home city of San Francisco have passed laws restricting its rentals.

Airbnb’s rapid growth — the number of hosts and active listings grew more than 20% in both 2018 and 2019 — has also made it difficult for the company to ensure quality. Last November, Airbnb promised to verify all its listings to make sure they match the photos on its site. It also spent the last year removing party houses and tightening rules for guests after a deadly 2019 shooting at an illegal Airbnb house party in California.

Relationships with hosts and guests have been rocky at times. After multiple reports of racist behavior targeting guests, Airbnb instituted a nondiscrimination statement that all guests and hosts must sign. It won’t display a guest’s profile photo until a property is booked, so a host can’t deny a room based on a guest’s race.

And earlier this year, hosts revolted after the company let guests cancel bookings and get full refunds due to the pandemic. Airbnb responded by promising $250 million to hosts to help make up the shortfall.

Cary Gillenwater, a university professor and Airbnb host in Duivendrecht, The Netherlands, said the company didn’t provide much financial assistance to him, even though he let many guests cancel without penalties.

Gillenwater usually makes more than $21,000 each year renting out a room on his property with its own entrance. This year, he’ll be lucky to make $2,500. He’s looking into renting the room to office workers to use during the day.

Despite his experience, he’s considering investing in Airbnb and thinks it will continue to grow. Home sharing is invaluable for his family of five, he said, because it’s difficult to find hotel rooms that are large enough.

“I feel like there is a future for them, but we have to get through all this first,” he said.