COLUMBUS, Ohio/RALEIGH — For many, it’s not Christmas without the dance of Clara, Uncle Drosselmeyer, the Sugar Plum Fairy, the Mouse King and, of course, the Nutcracker Prince.

But this year the coronavirus pandemic has canceled performances of “The Nutcracker” around the U.S., eliminating a major and reliable source of revenue for dance companies already reeling financially following the essential shutdown of their industry.

“This is an incredibly devastating situation for the arts and in particular for organizations like ours that rely on ticket sales from the Nutcracker to fund so many of our initiatives,” said Sue Porter, executive director of BalletMet in Columbus, Ohio.

“The Nutcracker” typically provides about $1.4 million of the company’s $2 million in annual ticket sales, against a $7 million budget. That money goes to school programing and financial aid for dance class students, Porter said. It’s the first year since 1977 that the company isn’t staging the ballet in Ohio’s capital.

The cancellations have meant layoffs, furloughs and salary cuts, with companies relying heavily— sometimes exclusively — on fundraising to stay afloat. Beyond their financial importance, “Nutcracker” performances are also a crucial marketing tool for dance companies, company directors say.

Children often enroll in classes for the chance to dance in the performances as mice, young partygoers and angels, among other supporting roles. For adults, the shows are sometimes their initial experience watching live dance.

“It tends to be the first ballet that people see, the first time they experience attending a production, that thrill when the curtain goes up, the hush of the crowd,” said Max Hodges, executive director of the Boston Ballet. “So for that reason it’s a key part of the pipeline in welcoming audiences into the art form.”

After deciding to cancel this year’s live performances, the Boston Ballet will use archived footage of past performances for a one-hour version to be shown on television in New England. The annual $8 million in “Nutcracker” ticket sales accounts for about 20% of the company’s annual budget.

The pandemic has cost the arts and entertainment industry about 1.4 million jobs and $42.5 billion nationally, according to an August analysis by the Brookings Institution.

The economic vulnerability inherent in arts organizations is exacerbated when they rely on a major seasonal event — like “The Nutcracker” — for large portions of revenue, said Amir Pasic, dean of the School of Philanthropy at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

Other cancellations this year include performances by the New York City Ballet, the Charlotte Ballet, the Milwaukee Ballet, the Sacramento Ballet and the Kansas City Ballet, which is forgoing about $2.2 million in ticket sales.

Making it through this season is tough enough, but “if this goes beyond next year, then I think we’ve got some serious issues to attend to,” said Jeffrey Bentley, the Kansas City Ballet’s executive director.

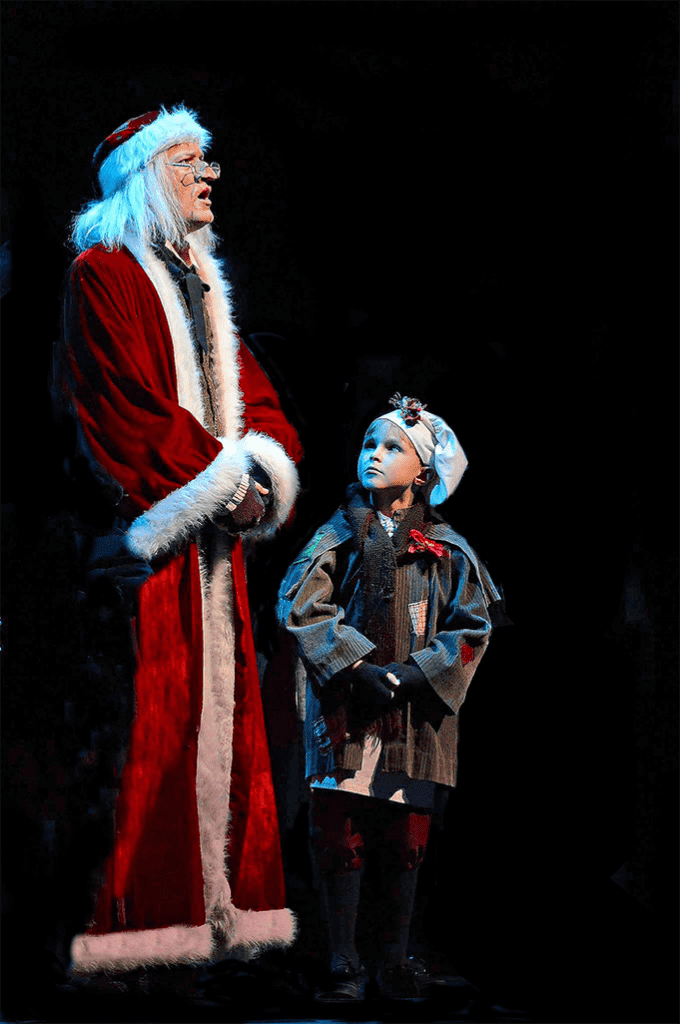

Raleigh’s Theatre in the Park is home to Ira David Wood, III’s “A Christmas Carol”, which has been performed annually since 1974 and named one of the “Top 20 Events in the Southeast.” In a recent press release, the company announced that the musical comedy adaptation of the Dickens classic will not be presented live in 2020, and instead will be transformed into a streaming event.

For its part, the Carolina Ballet company in Raleigh, has undertaken a “virtual season” this fall. Patrons and supporters can access classes and rehearsals of performances that had been slated to take place live. At this time, the company is still optimistic about offering their flagship performance of the Nutcracker, featuring live orchestra music with members of the North Carolina Symphony; however, they note that a virtual rehearsal and performance schedule is being planned as an alternative and will be announced at a later date.

Still others are proceeding, for now, with solid plans for live performances. The Eugene Ballet in Oregon canceled its normal four-state tour but expanded its stage offerings from four to 10 performances, with a socially distanced audience of 500 in a 2,500-seat auditorium. The company is shortening performances to 70 minutes, reducing the number of student participants and going without a live orchestra.

“We’re just all trying to be resilient, and our dancers are champing at the bit to get in the studio and start rehearsing things,” said Eugene Ballet Artistic Director Toni Pimble.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.