The former major leaguer sat in front of a plate of barbecue, making eye contact with me across the table.

His eyes darted hard to the left. After returning his gaze to me, he cut them left again.

Assuming someone attractive must have entered the restaurant, I casually looked over my shoulder, dipping my head slightly as I did so.

“That’ll get you hit in the neck,” he said, then put a fork full of greens into his mouth.

That was lesson one on how to steal signs.

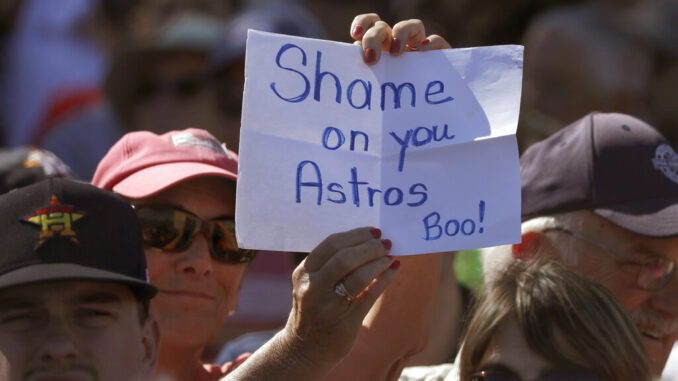

With the Houston Astros advancing to the ALCS, one step away from a return trip to the World Series in a year when they’re serving their penalty for a high-tech sign-stealing scheme, the issue is once again at the forefront of baseball debate.

It’s as old as the game itself and as diverse as the people who have played it.

The big leaguer, who played for four seasons in the majors and 14 as a professional, was demonstrating one of the ways the art could be used.

The technique he was teaching was one he used when he got to first base. The idea wasn’t to then communicate any stolen information to the batter. His teammate at the plate was on his own. He planned to use whatever he stole for his own benefit.

When stealing second, a baserunner would prefer to go on an off-speed pitch, such as a curve or change-up. As the name implies, those pitches don’t reach the plate as quickly as a fastball, giving him a few fractions of a second more to slide in safely ahead of a catcher’s throw.

He also preferred to run on pitches aimed at the lower part of the strike zone because they had a higher likelihood of ending up in the dirt, which would render the catcher nearly helpless in throwing him out.

So, while leading off from first base and watching the pitcher intently to determine if he was going to throw to first in a pickoff attempt, he would try to peek in at the catcher’s signs.

“You can’t move your head at all,” he cautioned.

There are rules about sign-stealing that are as old as the game itself, and they’re enforced strictly. A pitch in the neck your next time up appears to be the maximum sentence, and it can be rendered even if a defendant is only suspected of the crime.

His head remains locked in place, giving the illusion that his attention is focused entirely on the pitcher. Meanwhile, his eyes dart two, maybe three times toward the catcher, hoping to time it for when he was flashing signs to the pitcher — certainly no more than that. Otherwise …

“That’ll get you hit in the neck,” he said.

Even taking all the precautions, he sometimes got busted.

“There were a few times I’d look in and see this,” he said, hanging his hand down between his knees, like a catcher giving signs to a pitcher, and flipping an upside-down bird to the baserunner who’d better watch his neck the next time at-bat.

The actual stealing of a sign isn’t all that difficult. He offered to attend a college game with me — before the pandemic wiped out the season — claiming he could teach me before the day was over.

Signs have to be relatively simple, he explained, “because pitchers are dumb and need to be able to remember them.” It’s why interns watching a video feed could decode the signs fast enough to communicate what was coming to the dugout.

Signs coming from a coach or manager in the dugout are more complex, with indicators that need to be identified and dozens of false movements to camouflage the actual message. With some patience, however, they can be cracked as well, particularly if, as he often jokes about his own MLB career, you spend a lot of time on the bench watching.

There are other ways to tell what pitch is coming, though, short of actually decoding the signals. It’s what complicates the whole unpleasant business around the Astros. Far from binary, sign-stealing is a continuum. At one end is just being observant of the world around you — what old-schoolers would call “heads-up baseball” — and at the other are cameras and trash cans. Somewhere in the large, gray area in the middle, you might get hit in the neck.

“If you’re a right-handed batter,” he explains, “and before the pitch comes, you see the shortstop or second baseman taking a couple steps to his left, do you think maybe the pitch might be on the outside part of the plate?”

A righty is more likely to hit an outside pitch toward the first-base side of the field — his “opposite field” — so, after seeing the catcher’s sign, an infielder may take a few steps in that direction in anticipation of that happening.

“Now, in the majors, or even anything above the very low minor leagues, the infielders are going to wait to move until the pitch is on its way,” he added. “But in college, you might see that.”

No one could say that the batter is cheating by noting this movement and preparing for an outside pitch, but technically, he’s “stolen” the sign.

So, while there may be no one watching video of the signs or banging cans in the dugout this postseason, you can rest assured that players all over the field are still doing what they can to try to figure out what’s coming.

And if you see a pitch headed toward the neck of an Astros batter, you’ll know why.