LOS ANGELES — Athletes Stephen Scherer, Jeret Peterson and Kelly Catlin have two things in common: They all reached their dream of becoming Olympians, and they all died by suicide.

Olympians are known for pushing their bodies to the extreme but much less understood are the mental and emotional rigors paving their road to greatness. Michael Phelps, the most decorated Olympian in history, says he had suicidal thoughts even at the peak of his remarkable swimming career and calls depression and suicide among Olympic athletes an “epidemic.”

Phelps is opening up about his mental health struggles in “The Weight of Gold,” a new documentary that premiered last week on HBO. The film explores depression and suicide among the world’s top athletes and what should be done to address the problem.

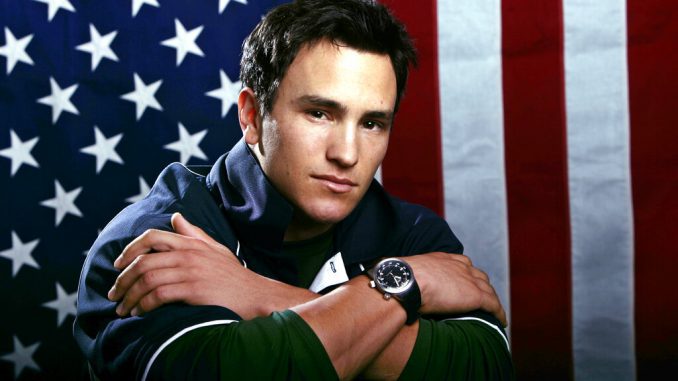

Other high-profile Olympians including speed skater Apolo Anton Ohno, snowboarder Shaun White, skier Bode Miller, hurdler Lolo Jones and figure skater Sasha Cohen also detail their own struggles in the film.

“It was important for me for the American public to see, ‘Hey, you have celebrated these athletes and it’s been amazing that you’ve done that.’ But it’s not all what you think it is,” said Ohno, who has won two gold, two silver and four bronze medals.

Like Ohno, the vast majority of Olympians spend most of their childhoods competing in their given sport. As they progress, competition becomes the main focus of their lives before family, friends, school or fun. For years they work toward that goal for what amounts to a competition that lasts minutes or mere seconds. The difference between winning and losing can be a fraction of a second, and millions are watching.

And then, it’s over. Either for another four years or forever, depending on the athlete and the sport.

“It does define you, and you lose your human identity,” said Jeremy Bloom, a three-time world champion skier and two-time Olympian. “That’s where it becomes dangerous. Because at some point, we all lose sports. We all move on. We all retire or the sport kind of shows us the door because we age out. And then we’re left to redefine ourselves.”

That becomes the breaking point for some athletes.

Bloom’s friend, aerial skier Jeret “Speedy” Peterson, killed himself in 2011 just a year and a half after winning a silver medal. He was 29.

To Bloom, Peterson had always seemed like “the happiest guy.” Except the night Peterson knocked on his door at the Olympic Training Center in Lake Placid around 2005.

“He was in tears. I’ve never seen him cry. He’s like, ‘I just need to talk to you,'” Bloom said recently from his home in Boulder, Colorado. “He really opened up to me about some of the mental struggles that he was he was dealing with.”

But Bloom said he “was not equipped at all.

“I had no idea the things to ask, the things to say. I just felt like he was having a bad night,” he said. “And I wish I could go back to that moment and know what I know now and be able to be a better support for him … And so I said, ‘Well, I better educate myself, better get smarter about it, and I better start talking about it because that’s what Jeret would want me to do.'”

Phelps, a co-executive producer on “The Weight of Gold,” said the need for change also is what drove him to speak up. He and other Olympians are calling on the International Olympic Committee and the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee to do much more to address the problem.

Phelps said the first step is “treating people like humans” instead of something on an assembly line.

“We’re just products,” the 35-year-old Phelps said from his home in Scottsdale, Arizona. “It’s frightening. It’s scary. And it breaks my heart. Because there are so many people who care so much about our physical well-being but I never saw caring about our mental well-being.”

In a statement to The Associated Press, the IOC said it “recognizes the seriousness of the topic” and assembled a team of international experts to review scientific literature on mental health issues among elite athletes in 2018, resulting in a mental health working group. The committee said the topic has been discussed more openly at forums and panels in recent years and that the IOC has launched a series of webinars to help athletes cope with COVID-19, and plans other initiatives, including a helpline.

Bahati VanPelt, chief of athlete services with the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee, said in a statement that the organization has “recognized we can improve.”

“In 2019, we took the important step of creating a dedicated athlete services division — separating athlete care and mental health services from high performance — to differentiate these services and ensure athletes can access resources and assistance without concern or hesitation,” he said. “We also created a mental health task force comprised of athletes and experts together to inform our work and help us improve athlete health and well-being.”

He said the committee has broadly expanded services, including more mental health officers and counseling, and is committed to keep mental health a top priority.

While some athletes have commended the changes, others like Ohno and Phelps feel like there’s much more to do.

“Clearly there’s a need for better resources because Olympic athletes are dying,” said “The Weight of Gold” Director Brett Rapkin. “They have this incredibly unique psychological journey they go on and it needs to be paired with appropriate resources to handle it. Those things clearly aren’t there.”