LOUISVILLE, Ky. — For months, Charles Booker languished in the shadows, talking about racial and economic justice in a long shot bid to take on Mitch McConnell, the Republican leader of the U.S. Senate. Then came a national eruption over the deaths of Black Americans in encounters with police.

Now, Booker’s bid for the Democratic Senate nomination from the left wing of Kentucky politics is on the rise, creating an unexpectedly strong challenge in Tuesday’s primary to the party-backed favorite, former Marine fighter pilot Amy McGrath.

Booker has been helped by the endorsement of Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and the state’s two largest newspapers. It’s created a sense of momentum and led to a surge in fundraising, money that Booker has used to slam McGrath, the long-time front-runner, in TV ads. It also has added a measure of uncertainty to the script in Democrats’ uphill efforts to topple McConnell, who is seeking his seventh term.

“Over the past couple of weeks, you all have seen a shift,” Booker, a freshman state lawmaker, said at a rally this past week in his hometown of Louisville. “There is something in the atmosphere. Something is really going on here. We all are a part of history.”

Booker, 35, found the spotlight during the outbreak of protests against police, fueled in part by the death of Breonna Taylor, a Black EMT shot by Louisville narcotics detectives who knocked down her front door but found no drugs. Booker marched with protesters and felt the sting of tear gas. His voice turned raspy from speaking so much.

“To see people mourning in the streets and crying out — demanding humanity, just demanding justice for everybody — it lit a spark,” Booker said.

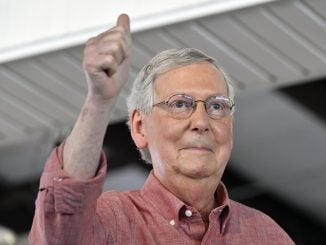

Republicans, too, seem to sense a moment of political change. McConnell, the Senate majority leader, mentions Taylor almost daily and has embraced legislation intended to overhaul police practices.

“We’re still wrestling with America’s original sin,” McConnell told reporters last week.

Despite the political upheaval, McGrath’s advantages in the primary are considerable. As a U.S. House candidate in 2018, she drew national attention with ads highlighting her military service, and that helped amass an extraordinary money advantage over Booker and other challengers. She is also running close to the political center in a state that tilts conservative, while Booker is unabashedly progressive.

“I have faith that Kentuckians know I’m the best candidate to fight for them and to defeat Mitch McConnell,” McGrath said.

Booker, who grew up poor in an inner-city neighborhood, is campaigning on universal health care, anti-poverty programs and criminal justice changes. Under the slogan “from the hood to the holler,” he claims a kinship with poor rural whites who he says are facing the same economic struggles he did.

The protests sweeping the country, Booker said, are “about people rising up and demanding real, structural change” to combat what he calls “institutional racism” and “generational poverty.” He says the predominantly African American neighborhoods where he grew up share more in common with Appalachia than with the rest of Louisville.

State Democratic Rep. Angie Hatton, who represents an Appalachian region in southeastern Kentucky, said Booker’s economic message seems to be catching on in her district.

“Poor is poor,” Hatton said. “And we may see differently on some social issues … but when it comes down to it, what my district needs is assistance with poverty and ways to help bring us out of poverty with good-paying jobs with health insurance. And his needs the same.”

Booker’s focus on poverty helped him win endorsements from the stars of the progressive movement. In addition to Sanders, he has been endorsed by Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y. He also gained the backing of former two-term statewide officeholder Alison Lundergan Grimes, who lost to McConnell in 2014.

“We’re going to win this race,” Booker said. “This is our time.”

But it remains to be seen how the backing from the left will play with the state’s voters. McGrath, who is spending millions on TV and radio ads for the final week of the campaign, said, “I don’t think Kentuckians want people from outside our commonwealth telling them how to vote.”

Another complication for Booker is that he risks splitting the vote with fellow progressive Mike Broihier, while McGrath steers a more centrist course. The unprecedented way Kentucky’s primary election is being held — with widespread mail-in absentee voting due to the coronavirus — is another wild card. Many Kentuckians voted early.

“We’ve all heard people say, ‘I might have voted for Charles if I’d realized he had a chance,'” Hatton said.

Local officials in some counties, including the state’s two most populous that cover Louisville and Lexington, say they won’t release any results until all the votes are counted. County clerks statewide must submit vote totals to the secretary of state’s office by June 30, a week after the election.

A tense wait for primary results is something few would have predicted earlier this year, when McGrath seemed on a glide path to the nomination. She scored the national party’s backing early and thanks to her incumbent-level fundraising has been on the airwaves with TV ads since last year.

Democratic strategist Mark Riddle said Booker has successfully “captured a moment and sometimes moments define campaigns.”

“The question is, does he have enough closing speed to catch her?” he said.