North State Journal’s 100 in 100 series will showcase the best athlete from each of North Carolina’s 100 counties. From Alamance to Yancey, each county will feature one athlete who stands above the rest. Some will be obvious choices, others controversial, but all of our choices are worthy of being recognized for their accomplishments — from the diamond and gridiron to racing ovals and the squared circle. You can see all the profiles as they’re unveiled here.

Edgecombe County

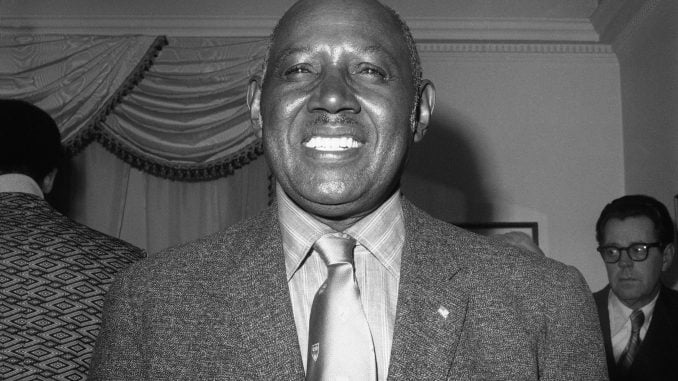

Walter “Buck” Leonard

It’s difficult to quantify just how great a hitter Walter “Buck” Leonard was since he came along before Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier and played his entire career in the relative anonymity of the Negro Leagues.

So leave it to fellow Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, who played briefly against Leonard before moving on to the San Francisco Giants, to provide a description.

“Trying to sneak a fastball past him,” Irvin said, “was like trying to sneak a sunrise past a rooster.”

Playing his entire 17-year career for the Homestead Grays, the Negro League equivalent of the old New York Yankees, the hard-hitting first baseman led his team to nine straight Negro National League pennants from 1937-45, including back-to-back World Series titles in 1943-44.

Although record-keeping from that era wasn’t like it is today and statistics vary depending on the source, Leonard and teammate Josh Gibson were annually among the league leaders in home runs, runs scored and RBI. Known as “the Black Lou Gehrig,” he finished his career with a .320 batting average and .527 slugging percentage.

Leonard was 45 when Robinson finally broke through with the Dodgers and opened the door for all players of color. Despite his advanced age, both the Pittsburgh Pirates and Washington Senators offered him major league contracts. But he turned them down, saying, “I knew I was over the hill. I didn’t try to fool myself.”

He might have been over the hill as a player, but he still had plenty left to give once he left the game. At the age of 52, he earned the high school diploma he was denied as a youngster because his hometown of Rocky Mount didn’t have a school at the time that allowed education for African American students. He was an energetic advocate for civil rights and an ambassador for Negro League Baseball until his death at the age of 90.

Elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972, he was ranked No. 47 on a list of the 100 greatest players of all time by The Sporting News in 1999. He was one of only five players to make the list who played most or all of their careers in the Negro Leagues.