The year was 1997. Andy Thompson had an idea. Adam Silver liked his plan.

Neither had any clue what they concocted.

The ESPN and Netflix documentary “The Last Dance” — the story based around Michael Jordan and the 1997-98 Chicago Bulls — premieres Sunday night with the first two episodes of the 10-part series. And the images from that season exist because of the notion that Thompson had and Silver, now the NBA commissioner but then the person in charge of NBA Entertainment, helped arrange.

Thompson, who already had been working at NBA Entertainment for about a decade, suggested embedding a crew with the Bulls. Silver made some phone calls. They were off and running.

“It’s almost hard to understate how famous Michael was and how popular this Bulls team was,” Silver told The Associated Press. “And so, Andy’s view was, ‘We need to find a way to capture this team in its glory.’ And there were no such things as multi-part documentaries on sports on television back then.”

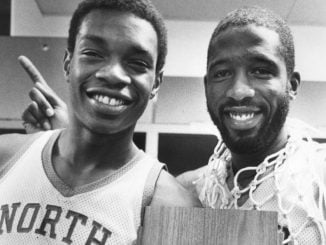

But there had been some examples of the storytelling that Thompson — the brother of former NBA player Mychal Thompson, the uncle of Golden State Warriors guard Klay Thompson — was pitching to Silver. Specifically, Thompson was moved by the tale of the 1986-87 Edmonton Oilers, a video called “The Boys On The Bus,” which chronicled a season with Wayne Gretzky and the eventual Stanley Cup champions.

“No one in the NBA had ever done this,” Andy Thompson said. “And you’re not just doing this with a run of the mill NBA team. You’re doing this with the greatest player in the history of the game in Michael Jordan, who was very protective of his image and his privacy.”

He got to know Jordan a bit while working at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. He had worked closely with Ahmad Rashad, a Jordan confidant, through “NBA Inside Stuff,” a show Rashad hosted. And Andy Thompson knew Jordan once idolized his brother, so much so that he wore puka shell necklaces and once scribbled his name on a notebook as “Mychal Jordan” until his mother saw it and wasn’t pleased.

“Because of his respect and admiration for my brother, obviously, Michael and I connected,” Andy Thompson said.

Silver approached Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf first, then had to convince then-coach Phil Jackson — who also agreed, albeit with some conditions that if he didn’t want the crew around at certain times they would give him space. And in the end, Jordan had to sign off as well.

Silver also made the financial aspect work, running that part past then-Commissioner David Stern. The project had plenty of other people involved and was costly; high-definition video used today didn’t exist at that time, but Thompson had already made the decision to chronicle the season on very costly, high-quality film.

“I’ll take David’s quote and apply it to Andy,” Silver said. “Andy had an unlimited budget, then he exceeded it.”

Thompson’s crew shot hundreds of hours of film. They knew every trick; if cigar smoke was in the air, it meant Jordan was nearby. The crew captured him one day in the locker room, cigar in his mouth, baseball bat in his hand. Another interview that Thompson won’t forget is one with guard Steve Kerr, who escaped to the shower area and was seated alone before what became the final game of the season.

Having a brother in the NBA had familiarized Thompson with locker-room culture, when to push, when to back off.

“When to shut up, when to be a fly on the wall,” Thompson said. “That gave me a huge advantage in dealing with players. I wasn’t afraid, I wasn’t intimidated. I could speak their language, so I could develop relationships quicker because of that. And that’s what helped me navigate the course of the season because access didn’t just happen overnight. There was a feeling out process for us and the team and the team for us.”

The footage, until it was unearthed for this project, had been locked in a vault at NBA Entertainment. Silver said many people — Spike Lee, Danny DeVito and more — expressed interest in putting together the documentary over the years and that it became a running joke between he and Jordan if it would ever be seen.

Nearly a quarter-century later, the big moment has finally arrived.

“We made it happen, but I would only say in all seriousness, this would not have happened if we had a specific project budget,” Silver said. “We would have had a zero under revenue and a large number under expense. I think it was more a gut feeling we had that it was our obligation to do this and we would spend what was necessary to capture what we knew was one of the greatest athletes and one of the greatest teams of all time.”