STAMFORD, Conn. — Purdue Pharma, the company that made billions selling the prescription painkiller OxyContin, has filed for bankruptcy in White Plains, New York, days after reaching a tentative settlement with many of the state and local governments suing it over the toll of opioids.

The filing was anticipated before and after the tentative deal, which could be worth up to $12 billion over time, was struck.

“This settlement framework avoids wasting hundreds of millions of dollars and years on protracted litigation,” Steve Miller, chairman of Purdue’s board of directors, said in a statement, “and instead will provide billions of dollars and critical resources to communities across the country trying to cope with the opioid crisis. We will continue to work with state attorneys general and other plaintiff representatives to finalize and implement this agreement as quickly as possible.”

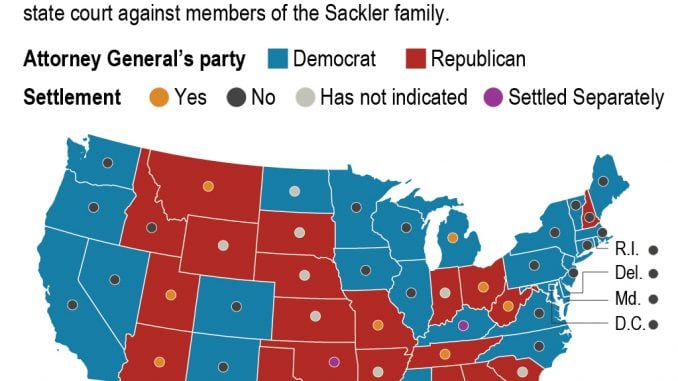

But legal battles still lie ahead for Stamford, Connecticut-based Purdue, which is spending millions on legal costs as it defends itself in lawsuits from 2,600 government and other entities. About half the states have not signed onto the proposal. And several of them plan to object to the settlement in bankruptcy court and to continue litigation in other courts against members of the Sackler family, which owns the company. The family agreed to pay at least $3 billion in the settlement plus contribute the company itself, which is to be reformed with its future profits going to the company’s creditors.

The opioid crisis has hit virtually every pocket of the U.S., from rural towns in deeply conservative states to big cities in liberal-leaning ones.

The nation’s Republican state attorneys general have, for the most part, lined up in support of a tentative multibillion-dollar settlement with OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma, while their Democratic counterparts have mostly come out against it, decrying it as woefully inadequate.

Some of the attention regarding the partisan divide has focused on the role played by Luther Strange, a Republican former Alabama attorney general who has been working for members of the Sackler family, which owns Purdue Pharma.

People familiar with the negotiations say he was at a meeting of the Republican Attorneys General Association over the summer, sounding out members about a settlement months before a tentative deal was struck this week.

North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein, a Democrat, was one of the lead negotiators on the settlement and said that Strange played a big role.

“He was lawyer to the family, and so we had multiple discussions with the family in which I indicated that a supermajority of states could agree to a deal if the Sacklers would simply provide more certainty as to the payment,” Stein said in an interview. “Almost all states would agree to the deal if the Sackler family would guarantee it 100%. Just make a payment. Those were discussions we had. The Sacklers rejected those offers and said it was take it or leave it, and I’m leaving it.”

Under the proposed deal, the company would declare bankruptcy and remake itself as “public benefit trust,” with its profits going toward the settlement. An Associated Press survey of attorney general offices shows 25 states and the District of Columbia have rejected the current offer.

The only states with Democratic attorneys general to sign on are Mississippi and Michigan, which is one of the few states that haven’t actually sued Purdue.

Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel noted the partisan split in a statement this week.

“While I have tremendous respect for my Democratic colleagues who have elected to opt out of settlement discussions,” she said, “ultimately each attorney general is obligated to pursue the course of action which is most beneficial to our respective states.”

The Republican-led attorney general offices in Idaho and New Hampshire have publicly rejected the settlement. Several GOP-led states have not said where they stand, but people with knowledge of the negotiations say they are accepting the settlement.

The GOP attorneys general have generally contended that getting a settlement now is better than uncertainty and years of litigation, while the Democrats have mostly argued that the deal does not provide enough money and does not hold adequately accountable members of the Sackler family.

“The Sacklers have blood on their hands,” said Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings, a Democrat.

The states that have refused to sign on are expected to object in bankruptcy court and to seek to continue lawsuits in state courts against Sackler family members, who have denied wrongdoing.

“I don’t think you should read a whole lot into it,” Iowa Attorney General Tom Miller, a Democrat, said of the partisan divide. “My view is it’s a pretty close call to join or not. There are good arguments on both sides. All my colleagues who have made their decisions have made them in good faith.”

Miller said he expects a bipartisan group of states to keep working together on possible settlements with other defendants in the opioid cases.

Paul Nolette, a Marquette University political scientist, said in an email that the GOP attorneys general and local governments “don’t see this as a bad deal under the circumstances.” But he said Democrats have been stung by a backlash over settlements over foreclosures years ago, and they “see political risks for not pushing for more.”