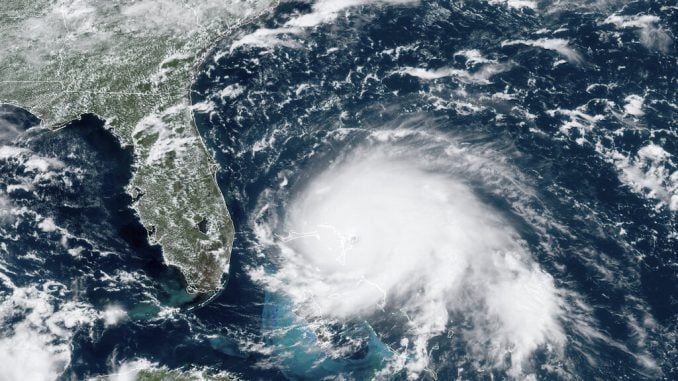

It may sound strange when talking about a storm that once had 185 mph winds, but calm weather high in the atmosphere has left powerful Hurricane Dorian stalled east of the Florida coast. While this has been horrible for the Bahamas, where the storm’s pounding has been relentless, it may help spare Florida a bit, meteorologists said.

Usually the upper atmosphere’s winds push and pull hurricanes north or west or at least somewhere. They are so powerful that they dictate where these big storms go.

But the steering currents at 18,000 feet above ground have just ground to a halt. They are not moving, so neither is Dorian.

After reaching record-tying wind speeds on landfall in the Bahamas, the storm just stalled. Its eyewall first hit Grand Bahama Island Sunday night, and 18 hours later part of the eye still lingered there, meteorologists said. The hurricane center late Monday called the storm “stationary” after several hours of crawling at 1 mph.

“This is unprecedented,” said Jeff Masters, meteorology director at Weather Underground who used to fly into hurricanes. “We’ve never had a Category 5 stall for so long in the Atlantic hurricane record.”

What’s happening — or more aptly, not happening — has been an ongoing battle between high pressure systems that push storms and low pressure systems that pull them.

A high pressure system in Bermuda has been acting like a wall, keeping Dorian from heading north. But a low pressure trough moving east from the Midwest has eroded that high and is trying to pull Dorian north. Those two weather systems “are fighting it out and neither is winning,” Masters said.

Think of it like a tiny paper boat or a pebble in a stagnant pond, which just doesn’t move, said Colorado State University hurricane researcher Phil Klotzbach.

Air — high off the ground and closer to where people live — is often stagnant in the summer and this is an extreme version of that, Masters said.

In 2017, Hurricane Harvey got stuck when steering currents collapsed, absolutely drenching Houston, but that wasn’t as powerful a storm as Dorian, Klotzbach said.

Usually hurricanes that don’t move eventually kill themselves because they churn up colder water from deep below the surface and storms need warm water as fuel, Masters said.

“It’s got to keep moving,” Masters said.

But the Bahamas and the Gulf Stream are one of the few places where warm water runs so deep. Stalling isn’t as much of a death sentence there as elsewhere, but it will still weaken the storm a bit, which is good for Florida and the U.S. East Coast, Klotzbach said.

And the longer Dorian stalls in the Bahamas, the more the low pressure system has a chance to erode the high pressure and pull the hurricane north and away from Florida, Masters said.