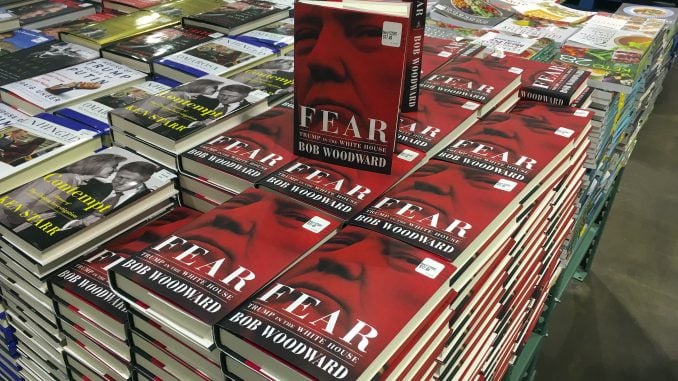

“I did not, and of course I looked for it, looked for it hard.” That was Bob Woodward, promoting his book on the Trump White House, “Fear,” replying to talk radio host and columnist Hugh Hewitt’s question: “Did you, Bob Woodward, hear anything in your research, in your interviews, that sounded like espionage or collusion?”

“You’ve seen no collusion?” Hewitt followed up. “I have not,” Woodward replied.

Can we take this as definitive evidence that there’s nothing to the theory, widely bruited these past two years by top intelligence and FBI officials, and by numerous Democrats, that President Trump or his campaign colluded with the Russians?

Not necessarily. As Woodward added, there’s always the possibility special prosecutor Robert Mueller or others know something we don’t.

But we also know none of Mueller’s indictments and guilty pleas point toward confirmation. And the prosecutor’s questions to Trump, quoted to Woodward, go to Trump’s motives for clearly constitutional acts, like firing former FBI Director James Comey.

So, as I wrote in my Wall Street Journal review of “Fear,” “Those anticipating Mr. Trump’s downfall for collusion with Russia will be disappointed by ‘Fear.’” Trump repeated Woodward’s statement, made after Comey informed the president-elect of the lurid allegations in the dossier prepared by former British intelligence agent Christopher Steele, that the dossier is “a garbage document” that “never should have been … part of an intelligence briefing.”

But that’s just about all that partisans like House Intelligence Committee ranking Democrat Rep. Adam Schiff refer to when they say that there’s plenty of evidence of Russian collusion already on the table.

Intelligence leaders like former CIA Director John Brennan and law enforcement officials at Comey’s FBI may have been prompted to investigate Trump’s Russian ties by the candidate’s bizarre statements praising Russian President Vladimir Putin, calling for accommodation with Russia and calling on Russia to release emails it may have obtained from Hillary Clinton’s illegal server.

But now, two years later, it’s apparent that Trump’s foreign policy is less friendly to Russia than his predecessor’s.

And it’s also clear, thanks to my Washington Examiner colleague Byron York’s reporting, that that Russia platform plank that was supposedly watered down at the Republican National Convention was actually toughened up.

The mainstream media, as is so often the case, simply got that story wrong in an apparent attempt to make Trump look bad. Recent examples: The Washington Post story on passport denials to Latinos that “withheld” and “distorted key facts,” according to the Huffington Post, and The New York Times hit piece on U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley that blamed her for overspending on curtains ordered in October 2016. Animus gone wild is the only explanation for such blunders in attacking a target-rich environment like the Trump administration.

Before 2016, I presumed that no serious person disagreed with the proposition that, as a general matter, it is undesirable to have law enforcement and intelligence agencies investigating political campaigns, particularly those of the party in opposition to the president. The potential for stifling free political debate and partisan competition is obvious.

I was open to the argument that in some circumstances, in some small number of cases, there might be exceptions to this general rule, going even beyond enforcement of campaign finance laws and regulations: the Manchurian Candidate exception. This appears to be what our intelligence and law enforcement leaders thought they were invoking when they launched their probes into and surveillance of the Trump campaign.

Now it appears that, beyond a generalized suspicion, they’ve been acting on nothing more than the Steele dossier. A document unverified, as Steele himself has admitted in a British court; a document made up entirely of hearsay from unknown and unavailable witnesses; a document bought and paid for by the Hillary Clinton campaign.

So it’s unsurprising to read that the intelligence and law enforcement agencies are resisting or slow walking a promised presidential order to declassify their documents and deliberations. And that congressional Democratic leaders are insisting that the agencies submit such declassified material to them before making it public. They don’t want people to know that intelligence and law enforcement agencies have been violating the general rule that they should not interfere in electoral politics.

“The entire inquiry,” Bob Woodward quotes Trump’s ex-lawyer John Dowd, “appears to be the product of a conspiracy by the DNC, Fusion GPS — which did the Steele dossier — and senior FBI intelligence officials to undermine the Trump presidency.”

Does Woodward disagree?

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and longtime co-author of The Almanac of American Politics.