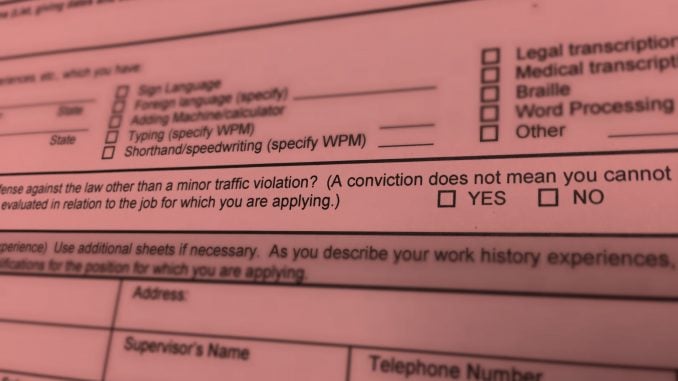

After a convicted criminal has repaid his debt to society, his reintegration into normal life is an issue about which everyone should be concerned. Unless he is given a lifetime sentence, he shouldn’t spend a lifetime paying for the same crime.While it’s true that the stigma of a criminal conviction can serve as a powerful deterrent to crime, at some point we begin hurting ourselves by narrowing the options available to those with a criminal record, making a return to a life of crime more attractive by comparison. Nationally, one effort to ease reintegration is a push to “ban the box.” The box, in this case, is the box on employment applications that asks prospective workers whether they have been convicted of a crime. Employers are still able to discriminate based on an applicant’s criminal history, but they can ask the question only after extending a conditional job offer. The idea is to avoid having employers perform an initial screen based on criminal history, but rather consider a person’s past in concert with other attributes the person brings to the table.Most liberal groups and many conservative ones favor the effort, and most agree that the practice of screening for a criminal past at the outset is detrimental to the organization doing the hiring as well as to those with criminal convictions and society at large.Predictably, liberal and conservatives favor different approaches. Liberals want to simply make it illegal for any employer to ask the question initially (with some exceptions). Conservatives prefer a narrower approach that would encourage businesses to wait until later in the hiring process, but not outlaw the question entirely.A third way was introduced into the General Assembly this week, and the bill deserves a chance. House Bill 233 was introduced by Democrats but has gained one Republican co-sponsor so far. It would leave the private sector alone but ban the box in state and local government hiring. Businesses often complain that government agencies apply rules to others that they don’t follow themselves. So having the state lead by example is not a bad idea.That being said, the bill needs some work. For instance, its current draft allows agencies to screen out convicts if the agency is “otherwise required by law to consider the criminal record.” But many agencies may have good reasons to screen applicants this way even if it is not required by statute. State and local agencies should have time to explain why they may need this discretion before it is outlawed. Then they can either be exempted by the bill, or another mechanism such as an executive override can be put in place, at least temporarily, while the agencies adjust to the new system.First, the state should carefully consider the evidence put forth by ban-the-box proponents. If that is compelling, the next step would be a ban for state government, or as in H.B. 233 both state and local governments. After legislators are comfortable with the state’s experience with the new practice, a public outreach campaign to businesses could follow. Considering how detrimental career criminals are to society, and how expensive they become to the state, spending public funds on the matter is not out of bounds.It may grate on some to see taxpayer dollars spent on influencing hiring practices in the private sector. That is understandable, but reintegrating ex-cons into society should be a core function of the penal system.When it comes to prisons, we should aim for one-time reformation, not lifetime customers.

Drew Elliot is a member of the North State Journal’s editorial board, separate from the news staff. Unlike other newspapers, the North State Journal does not publish unsigned editorials; the author or authors of every editorial, letter, op-ed, and column is prominently displayed. To submit a letter or op-ed, see our submission guidelines.