Learning isn’t necessarily cumulative. Human experience over the centuries provides lessons, some clearer than others. But each generation has to learn lessons anew, and some do not.

The lessons about economic growth taught over the long run of history are clear. Growth is not inevitable, and while riches may be accumulated, or appropriated, by the few in high positions, the lives of the very large majority throughout the centuries have been nasty, brutish and short.

The exception, the Great Enrichment, began some three centuries ago around the North Sea, in the Dutch Republic and England, according to economic historian Deirdre McCloskey, in societies when people began respecting and encouraging commerce, rather than resenting and scorning it.

They discovered that when people exchanged goods and services in free markets, with property rights secured by limited government and the rule of law, economies could grow in ways that improved the lives of not just the few but the many.

Suddenly, and not just for a moment, the great masses of people went from living on $3 a day, just barely subsistence, and in times of famine or war not even that, to $130 a day.

The 20th century proved full of lessons for how to produce extended and widely distributed economic growth — and how to squelch it. Growth occurs when free markets are allowed to operate in societies with high levels of trust and the rule of law.

It ceases, and living standards plummet, in societies where governments flood the economy with currency, try to control wages and prices, impose centralized economic planning, and outlaw voluntary market transactions.

Governments sometimes impose such measures temporarily in wartime, with various results depending on the course of the war. In peacetime, the results are destructive — in Weimar Germany, the Soviet Union, Mao Zedong’s China and, most recently, oil-rich Venezuela.

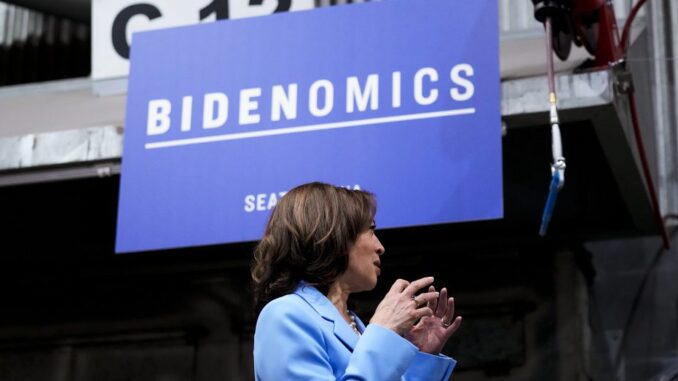

And, perhaps, in Kamala Harris’ America. Since President Joe Biden ended his candidacy for reelection four weeks ago, the vice president has said remarkably little about what policies she would pursue as president. Her website has had no issues section.

She has taken almost no questions and has undergone nothing like an intensive interview from the press — most members of which, in their enthusiasm for her candidacy, have shown no discomfort at her neglect.

Only last Friday did she begin talking issues, announcing “the first-ever federal ban on price gouging” — she read the word as “gauging” — “on food and groceries.” Presumably, this was an attempt to address an obvious vulnerability for any candidate with a Biden-Harris pedigree, the fact that administration policy, by showering money on consumers already flooded with lockdown-accumulated cash, stoked inflation that no voter under 60 had experienced as an adult.

But of course, this made no sense. The grocery business is highly competitive, with low profit margins — if one firm “gouges” consumers too much, they can go elsewhere. “It’s hard to exaggerate how bad this policy is,” wrote The Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell. “At best, this would lead to shortages, black markets, and hoarding.”

Rampell has since taken a different view after Harris’ actual speech backpedaled from her campaign’s fact sheet, but her initial take remains persuasive and in line with historic experience, including with the price controls imposed by former President Richard Nixon 53 years ago this month.

Similarly economically illiterate is Harris’ proposal to give first-time homebuyers a $25,000 government subsidy. Just as colleges and universities have vacuumed up government-subsidized college loans for their own purposes, so obviously developers and home sellers are going to raise their asking prices by $25,000 and pocket the subsidy.

As Jason Furman, head of former President Barack Obama’s second-term Council of Economic Advisers, said of the price-gouging announcement, “This is not sensible policy, and I think the biggest hope is that it ends up being a lot of rhetoric and no reality.”

Is it fair to argue that Harris has learned nothing from the dismal history of price controls on the basis of just one proposal? Yes, if it’s just the only thing she has proposed in a whole month as the de facto and de jure Democratic nominee for president.

And yes, as she has never personally renounced the similarly outlandish promises she made in 2019 in her campaign for the 2020 nomination — a ban on fracking, defunding the police, abolishing private health insurance, “snatching” drug company patents. Tweets from anonymous staffers ditching these policies don’t count.

The delicious irony here is that the party favored by college graduates, many of them smugly confident of their knowledge and wisdom, is nominating a candidate who has shown no sign of learning from the dismal history of economic ukases. Learning isn’t necessarily cumulative.

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and longtime co-author of “The Almanac of American Politics.”