RALEIGH — According to a recent update from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI), K-12 academic achievement across the state fell behind by between two and 15 months across various subjects during remote learning imposed on students due to pandemic school closures.

The data from NCDPI is the result of a partnership with SAS Institute, which visualized information to show the level of learning loss experienced by students in K-12. NCDPI announced the findings on its blog, where it will be publishing related monthly white papers going forward.

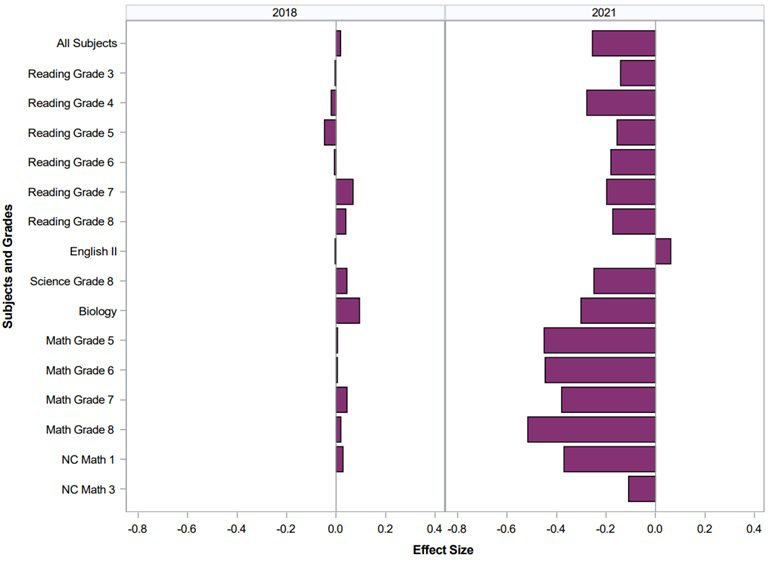

According to the related blog post, NCDPI’s Office of Learning Recovery (OLR) ”converted the statistical effect sizes presented in the Lost Instructional Time report into estimates of additional instructional time needed to get students back on track.” The average statewide individual student growth from 2020-21 was then converted into ”estimates of time based on national research calculations of average student growth by grade and subject.”

According to OLR, the new visualizations were created by using predictive data and comparing test scores pulled from the 2017-18 and the 2020-21 school years. In other words, they used test scores students were predicted to have based on results in previous years and the scores students actually earned.

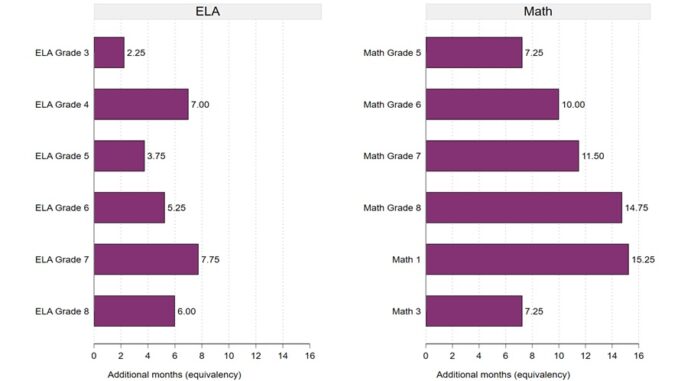

The results show that, depending on their grade level, K-12 students on average fell behind by just over two months to seven months and three weeks in the subject of English Language Arts.

When it came to math achievement, the drop was steeper, with students on average falling behind by seven months to 15 months depending on what grade the student was in.

In a media briefing prior to the release of the data, Jeni Corn, NCDPI’s director of research and evaluation at DPI’s Office of Learning Recovery, indicated the drop-off in math is likely linked to research showing higher math course teaching did not translate well in a remote instruction environment. She said support for lower grade level math was easier for parents to aid their students with than middle and high school math courses.

The visualized learning loss data provided by NCDPI does not consider any interventions that may have occurred during the current school year. The impact could also be worse due to the fact that not all students in the state took the tests used to compile the data.

The generalized nature of the data also does not allow for a school-by-school or district-by-district analysis. Calen Clifton, a research analyst working on the project said that the data “aren’t exact, and “are approximations intended to help communication.”

Districts across the state will be implementing various interventions to address learning loss similar to learning camps offered during the summer of 2021. According to OLR, the office will also be looking at the interventions being chosen by schools and analyzing the impact with a plan to publish their findings.