COLUMBUS, Ga. — Wayne Black was one of the few African Americans in the crowd as about 100 people gathered recently at the Republican Party headquarters near Columbus, Georgia, to hear from U.S. Senate candidate and football legend Herschel Walker.

A member of the Muscogee County Republican Executive Committee, Black said he found a certain promise in Walker’s candidacy, a GOP voice who could appeal to African Americans and others in Georgia who have traditionally voted Democratic.

“They identify with him from the standpoint of the American dream,” Black said. “You can start from nothing and if you work hard, you can achieve the American dream.”

But that optimism ran into headwinds about 100 miles to the north. As she left an Atlanta polling site, Wyvonia Carter said her choice in what might be the most competitive Senate race this year was not particularly complicated.

“You know I’m Black, right?” the 84 year-old said. “I’m a Democrat. That’s it.”

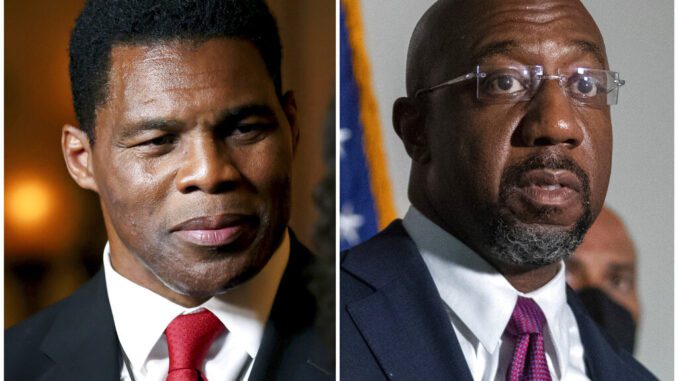

Voters for the first time have selected two Black candidates to represent the major parties in a Senate race. After handily winning their respective primaries on Tuesday, Walker will take on Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock in a general election campaign that could help decide control of the Senate.

The race will test whether Democratic gains in 2020 were a blip or the start of a political realignment in a rapidly changing state. In November 2020, Joe Biden was the first Democratic presidential candidate to carry the state in 28 years, and just two months later, Warnock and fellow Democrat Jon Ossoff flipped two longtime Republican Senate seats, handing their party a narrow majority in the Senate.

Black voters were crucial in helping Democrats secure those victories and will likely be decisive again this year.

The issue is less about whether Walker will break the bond that black voters have had with Democratic candidates. It is more about whether black voters, frustrated by a lack of progress in Washington on issues ranging from a policing overhaul to voting rights, simply sit this election out. In a close election, even a small change in voting patterns could be decisive.

Republicans hope Walker’s candidacy can at least neutralize the issue of race in the campaign.

“In this race, black Georgians will not have to contend with the race issue,” said Camilla Moore, chair of the Georgia Black Republican Council. “And I really do believe by culture, we’re socially conservative. I think Herschel just has to be Herschel and tell his conservative message.”

But in interviews in recent weeks, many black voters said they would not give Walker a second look because of his race. They said they were driven by policy considerations, and Walker, who was backed by former President Donald Trump and is generally in line with GOP orthodoxy, does not address their needs.

Louis Harden, a 58-year-old black voter in Atlanta, said he is backing Warnock because of the senator’s support for Medicaid expansion.

“It doesn’t matter about the color,” he said. “It’s just the issues, who’s going to get the job done.”

There are only a few modern instances in which two Black people have emerged as the nominees in a Senate race.

Democrat Barack Obama faced Republican radio host and former diplomat Alan Keyes in his 2004 Senate campaign in Illinois. More recently, South Carolina’s Tim Scott, the Senate’s only Black Republican, was unsuccessfully challenged in 2016 by Thomas Dixon, a North Charleston pastor.

But the Warnock-Walker matchup is unique because it is playing out in a far more competitive state than Illinois, a Democratic stronghold, or South Carolina, where Republicans are dominant. Also, the candidates in Georgia are already well known, representing two institutions that are revered in the South: church and football.

Walker, among Georgia’s most well-known sports figures, won a championship and the Heisman Trophy while at the University of Georgia in the 1980s. Warnock is the senior pastor at the Atlanta church where Martin Luther King Jr. preached.

“This is going to be a historic matchup,” said Stan Deaton, a scholar at the Georgia Historical Society.

But to make a dent in Warnock’s support among Black voters, Walker will need to do more to appeal to the Black community, said Leah Wright Rigueur, a political historian at Johns Hopkins University who has written about efforts by Black Republicans to broaden the party’s largely white base.

Republican candidates who do well among African American voters have the ability to craft a political identity that is independent from the party, something she said Walker has not done so far. Black voters also consider how a candidate treats his or her community and may view African American candidates who stick to Republican talking points more harshly than their white counterparts, Wright Rigueur said.

“And the reason why is because it’s viewed as a betrayal,” she said. “It’s viewed as community betrayal.”

Walker has largely hewed to Republican messaging about race. He has defended Trump against criticism that Trump was racist, he has accused Black Lives Matter of wanting to destroy the country and he has said “black-on-black crime” is far worse than violence by police. Walker has come under scrutiny over allegations that he threatened his ex-wife’s life and dramatically inflated his record as a businessman.

Warnock, the pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church, has embraced King’s legacy of racial justice and equal rights. After the killing of George Floyd by police in May 2020, Warnock expounded on the country’s struggle with a “virus” he called “COVID-1619” for the year when some of the first slaves arrived in what is now the United States. On Capitol Hill, he has attacked Republicans’ push for tighter voting rules as “Jim Crow in new clothes.”

Warnock “has a record of fighting to improve the lives of all Georgians,” Warnock campaign manager Quentin Fulks said in a statement, citing as examples Warnock’s efforts to forgive student loan debt and address the high rates of maternal mortality.

“The people of Georgia, no matter their race, will make the decision about who is up for the job and best able to represent the people of Georgia,” he said.

A spokesperson for Walker’s campaign, Mallory Blount, said all Georgians, regardless of race, are facing problems created by Democrats and that Walker is “sick and tired of politicians constantly dividing people based on the color of their skin.”

Walker told a House subcommittee last year while testifying against reparations for slavery that “Black power” is used to “create white guilt.”

In his memoir, “Breaking Free,” Walker said his mother taught him that “color was invisible” and doing right or wrong was what mattered.

“I never really liked the idea that I was to represent my people,” he wrote. “My parents raised me to believe that I represented humanity — people — and not black people, white people, yellow people, or any other color or type of person.”

Still, black Republicans in Georgia expect Walker to try hard to woo the African American community during the general election. They also believe his personal story about overcoming obstacles to reach the top ranks of college football and then the NFL will find an audience among black voters.

“Self-determination has always been a big thing in the Black community since we got out of slavery,” said Leonard Massey, who is black and is chairman of the Chatham County Republican Party in eastern Georgia. “He actually shows how to get to the next level.”